Holiday groups, new games, 30% off sale

0 RepliesA quick blog post about three things: therapy groups for Melbourne F-2 children in January 2025, 15 more Flex-It card games to teach Set for Variability/pronunciation correction in polysyllable words, and a bumper end of year Spelfabet online shop sale (use the code “Happy Holidays!” at the checkout for 30% off).

January therapy groups

We still have a few places in our 20-24th January therapy groups for young struggling readers/spellers (2024 Foundation to Year 2 children). If you know a young child in Melbourne whose school report says they’re not keeping up with peers on literacy, and who might like to join an intensive group, please let them know. More details are here.

We now have a bunch of kids who have been coming back most holidays, as young children are often too tired to do therapy outside school hours during term. Groups can be more fun than individual sessions, and allow children to make friends with peers who are also finding reading/spelling a bit tricky.

More Flex-It card games

A second tranche of 15 Flex-It card download-and-print games are now in the website shop, you can find them here. These games give children controlled practice trying a different target sound for a target spelling (Set for Variability/pronunciation correction), if their first attempt at sounding out a word isn’t successful, e.g. if they rhyme ‘very’ with ‘furry’ instead of ‘berry’.

Each printable game costs an Aussie dollar (or 70c for the rest of 2024) plus GST. Each prints in colour on three sheets of A4 cardboard. Print and laminate what you need, cut them up (or helpful older kids might like to flex their scissor skills) and you’re ready to play. The original 15 Flex-It games have also been improved slightly, so if you already have the first set, log back into the shop to download the new files (go to My Account, reset your password if it’s forgotten).

30% off everything in the Spelfabet shop

To congratulate everyone for getting through the year, we’re having a bumper 30% off everything sale in the Spelfabet online shop until the end of 2024.

Choose the things you want from the shop – embedded picture mnemonics, decodable books, games, quizzes, workbooks, whatever – then type “Happy Holidays!” into the coupon box at the checkout for the discount. If you dislike laminating and cutting up, we probably can’t post the printed Short Vowels game in the video below to you before Christmas, but postage on a class set costs the same as a single game, and would arrive anywhere in Australia before the 2025 school year (sorry we don’t mail them overseas).

May your festive season be full of rest, fun and love, from everyone at Spelfabet.

Literacy boosts language

6 Replies

Washington DC’s amazing Planet Word Museum has a great YouTube channel which includes a lecture called Eyes on Reading: Dr. Stanislas Dehaene with Emily Hanford about how learning to read changes the brain. I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the many kids I’ve known with whose language test scores vastly improved after they learnt to read and write, so I sat up and paid close attention when Dr. Dehaene said (starting at 16.15 on the video clock):

“…because you’ve learned to read, you are processing spoken language better. You are hearing the phonemes better and you are able to do phonological awareness tasks, you’re able to move phonemes around in your mind, you’re able to play with phonemes, and we found that there is almost a doubling of the brain activity for spoken language as a function of how good a reader you are, as a function of reading score. So that’s a huge transformation. We don’t fully know at the cellular level what it means, but there is a huge enhancement of responses in this area. We also found that the connection between these systems, if we look just at the anatomy of the connections of the brain with diffusion imaging, was reinforced “.

Matthew Effects and Spiral Causality

We’ve known since Keith Stanovich’s classic 1986 Matthew Effects article that reading boosts both language and cognitive skills. He explains this here:

Conversely, failing to learn to read has a negative impact on language and cognitive skills, and other negative knock-on effects, as Stanovich wrote:

“Slow reading acquisition has cognitive, behavioral, and motivational consequences that slow the development of other cognitive skills and inhibit performance on many academic tasks. In short, as reading develops, other cognitive processes linked to it track the level of reading skill. Knowledge bases that are in reciprocal relationships with reading are also inhibited from further development. The longer this developmental sequence is allowed to continue, the more generalized the deficits will become, seeping into more and more areas of cognition and behavior. Or, to put it more simply – and more sadly – in the words of a tearful nine-year-old, already falling frustratingly behind his peers in reading progress, “Reading affects everything you do.” (p390)

In 2011, Dutch researchers Suzanne Mol and Adriana Bus published To Read or Not To Read: A Meta-Analysis of Print Exposure from Infancy to Early Adulthood, in which they found:

“Print exposure explains 12% of the variance in preschoolers’ and kindergartners’ oral language skills,13% in primary school, 19% in middle school, 30% in high school, and 34% at undergraduate and graduate level…Although these outcomes do not permit conclusions about causality, the pattern of findings as well as a qualitative review of longitudinal studies suggests that spiral causality is plausible.”

Being literate helps us remember spoken words

In 2022 I was surprised by radio reports of a new, nationalist Italian Prime Minister with an Irish-sounding name: Georgia Maloney. OK, Italy and Ireland are both in the EU, but, mi scusi? Google to the rescue. Giorgia Meloni. Facepalm. I’d applied the wrong orthographic skeletons – ideas we form about a word’s spelling from its pronunciation. They’re what we correct/clarify when we hear an unfamiliar name, ask ‘how do you spell that?’, then don’t write it down. We’re just trying to mentally store a high-quality lexical representation (sounds, word structure, meaning and spelling).

Generating orthographic skeletons is linked to better word recall (see last year’s delightfully-titled article Déjà-lu: When Orthographic Representations are Generated in the Absence of Orthography), just as oral vocabulary knowledge boosts retention of written words (see other non-paywalled articles about this here, here, here and here). Words are learnt more easily, even by dyslexic children, when presented in both spoken and printed form. Spellings help us symbolise and store sounds/word parts in memory. Other research on this Orthographic Facilitation process can be found here, here and here.

We all know strong oral language is the foundation of strong literacy skills, but language and literacy intertwine across the lifespan in a reciprocal way, so that becoming literate boosts oral language skills, especially vocabulary. US education, cognitive science and fairness blogger Natalie Wexler’s recent post “Want children to be good speakers? Teach them to write” argues that writing instruction also improves comprehension and the ability to use formal spoken language. All of us at Spelfabet are about to do SRSD training, as research suggests their approach to writing also has positive spinoffs for other aspects of communication and wellbeing.

New NDIS guidelines

Australia’s new National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) guidelines say supports related to school education are not funded by the NDIS. Having been in local government, I find cost-shifting maddening, so I agree that every cent of NDIS funding should be spent helping people with disabilities to become more independent, find work, study and have greater choice and control over their lives.

Ideally, schools should be able to teach all children with disabilities who can understand and use language to read and write. As well as this being great for the kids, it would save the NDIS a lot of money helping participants overcome consequences of poor literacy, like not being able to read signage, food labels, recipes, shopping lists, timetables, text messages etc., let alone study or find work.

Some children with disabilities have major difficulties with phonological processing, memory, speech, language, attention, perspective-taking, restricted interests, sensory overload, motor planning and/or anxiety, which interfere with learning to read and write. Even if they have high-quality classroom teaching and small group intervention in their first three years of schooling, they still fall behind their peers. Their disabilities require specialised, individualised intervention not always available in schools to learn to read and write, and thus improve their language and life prospects generally. The longer this intervention is postponed, the more difficult and expensive it becomes.

Alison Clarke

Speech Pathologist

Autonomy’s great if it delivers success

7 Replies

The Australian Education Union dislikes our state’s new requirement to teach explicit, systematic, synthetic phonics in the early years, saying teachers already do phonics, must not be told how to do their jobs, weren’t properly consulted, and won’t cooperate. However, many teachers, including AEU members, are pleased by this new requirement. They see it as a vital social justice measure and a way to cut teacher workloads, and are disappointed by the AEU’s response.

I’m not sure why being told to do something you already do is a problem. Everyone is told how to do their jobs, including self-employed folk like me. I’m working on my Speech Pathology Australia Certification, and must comply with Fair Work, NDIS, Medicare, ATO and many other requirements.

The reading/learning science movement has been growing like topsy for years, so I’d be surprised if Education Ministers and the AEU haven’t had plenty of discussions about how to best teach literacy. Having been a union rep myself, I’d be amazed if AEU members went to the barricades to defend teaching approaches which lack strong evidence, or the resulting high differentiation workloads.

Teacher autonomy (not evidence-based practice) gets top priority in the recently-updated AEU Pedagogy Policy. Perhaps whoever invited Barbara Arrowsmith-Young to speak at the AEU office in 2017 led the policy review process. Has teacher autonomy been working well for this state’s struggling readers, and their teachers, who have a right to do high-quality work, and to see their students succeed?

New VAGO report

A new state Auditor-General (VAGO) report says our Education Department isn’t getting good value for the $1.2 billion dollars being spent over five years on its Tutor Learning Initiative. There’s substantial evidence (e.g. here and here) that high-quality, intensive small group intervention can help struggling readers catch up. Across the state in 2023, tutored kids’ test scores increased more than the median increase for all kids (great!), but less than matched kids who weren’t tutored (oh dear).

I’m sure many skilled, experienced tutors who understand reading/learning research provided high-quality intervention in many schools, and their students made a lot of progress. But what were tutors doing elsewhere? Balanced literacy (a balance of things that work and things that don’t)? Other ineffective programs/approaches? VAGO says tutoring was generally timely, but there were problems with targeting intervention, and making it appropriate to school context and student need. Workforce problems mainly affected secondary and F-12 schools.

VAGO concludes that many schools’ tutoring was not effective, and recommends a statewide, staged roll-out of effective programs. Data the Education Department already collects should be used to drive improvement. Absolutely.

What does good intervention look like?

Most kids who struggle to read and write have difficulty at the word level. Kids’ word-level reading and spelling improves when they do a LOT of well-targeted and sequenced reading and writing practice. If watching a Tutor Learning Initiative literacy session, I’d mainly want to see kids with eyes on text (in books, games, whatever) as they read aloud, or pencils in hand, writing, then reading back what they’ve written. I’d want to see tutors providing well-organised and sequenced, fast-paced work with immediate feedback and encouragement. They’d be helping kids get their reps up, and slam-dunk words into long-term memory for instant retrieval and thus fluency.

Take a look at the 90 second video about the Tutor Learning Initiative here: www.vic.gov.au/tutor-learning-initiative. I see children walking, sitting, talking, smiling … but can you see any children reading or writing? What does this mean? I’m not sure, but I’d promote this initiative with a very different video.

System support for the best teaching and learning

The AEU’s submission to our recent state government inquiry into education says on p2:

“Geoffrey Robertson KC correctly argues that “a real revolution in education will only come when a government ensures that its state schools set the standard of excellence. Then and only then will we have equity.” The idea of equality draws on notions that all people in our society are of equal value. This democratic principle is crucial to underpinning the provision of public schooling. Only through proper and fair funding of our schools and a system focused on supporting school staff to provide the best teaching and learning programs that then (sic) we can achieve equity.”

Typo/grammar aside, I couldn’t agree more. It’s time to close the school funding gap. I hope the Federal Next Steps report ensures that future Initial Teacher Education graduates know how to teach reading and spelling fast and well. I hope ongoing Tutor Learning Initiative improvements, and implementation of the VAGO report’s recommendations, help stacks of struggling kids catch up with their peers in 2025. And I hope AEU members can persuade their leaders that early, explicit, systematic phonics is (to paraphrase Snow and Juel) helpful to all children and their teachers, harmful to none, and crucial for some, and that autonomy to wander in the literacy pedagogy wilderness is highly overrated.

Dyslexia facts, myths and strategies

0 Replies

I’ve just listened to a great Ontario IDA Reading Road Trip podcast, in which the IDA’s Kate Winn interviews Dr Jack Fletcher about dyslexia facts, myths and strategies. Click here to listen to the whole thing yourself, and/or read the transcript, which includes references. For the time-poor and my own learning, here’s what I thought were key takeaways.

Defining and diagnosing dyslexia

Dyslexia is a word-level reading and spelling problem which results from a combination of biological and environmental factors. It’s a persistent inability to respond to the kind of explicit, intensive, instruction that works for most people.

Instructional response is the most important criterion for diagnosing anyone with a Specific Learning Disorder, especially dyslexia. Diagnosis should be based on multiple criteria, including progress monitoring measures from intervention, and norm-referenced achievement testing. Specialist dyslexia assessment tools aren’t helpful or necessary. Cognitive tests are only useful in identifying kids who are at risk in the first two years of schooling. After grade two, assessment should be focussed on academic measures of reading, spelling, and writing.

It’s not valid to diagnose dyslexia based on a discrepancy between cognitive skills and academic performance. Kids with reading problems with high and low IQs have the same difficulties with phonological awareness, rapid naming and so on. IQ tests have racial and social bias, so there are social justice issues associated with their use. A Pattern of Strengths And Weaknesses model is also a discrepancy model, is typically inaccurate and grossly under-identifies kids with learning disabilities. We also need to be aware of English Language Learners when identifying at-risk kids, so they’re not misidentified.

Related/co-occurring difficulties

Other kinds of learning disorders and difficulties often co-occur with dyslexia, such as problems with writing or mathematics. Kids with dyslexia often also have difficulties with attention and/or language needing separate intervention. Stimulant medication can help a child pay attention but it won’t teach them how to read. Learning to read words doesn’t guarantee you’ll know what they mean.

About 25% of kids with dyslexia have clinical levels of anxiety. Anxiety predicts a poorer response to intervention, so one US expert, Sharon Vaughn, has introduced five minutes of mindfulness meditation at the start of intervention sessions, to reduce anxiety.

Psychiatrist Shepherd Kellam studied an approach which prevented behaviour problems, but found this didn’t help kids improve their reading. So he introduced a reading intervention, and found that when they became better readers, the girls were less depressed and the boys were less disruptive. He also found that kids all knew who was struggling with reading, and that this was a source of anxiety.

Can dyslexia be prevented?

Many severe reading problems can be prevented if kids get the right kind of explicit instruction and reading experience in their first three years of schooling. About 40% of kids find it hard to learn to read well without really explicit and fairly intense instruction and early reading experience. This makes them aware of the sounds in spoken words and helps them grasp the idea that these sounds are what letters represent (the alphabetic principle) and develops their brains as mediators of reading. Early access to print gives the brain the kind of visual experience it needs to become an automatic reader.

If kids don’t learn to read in the first three years of schooling, it’s very hard for them fully develop their neural system and get the reading experience and vocabulary they need to become skilled, automatic readers. They can be taught to decode, but end up with persistent reading problems. Intervention in first and second grade is twice as effective as intervention after the third grade. It’s hard to differentiate reading problems due to biology and those which are due to environment. Brain scans of third grade poor readers who were not taught well and third grade poor readers at biological risk of dyslexia look the same.

Poor instruction is unfortunately still quite common, though teachers are not to blame, they always have good intentions. They just may not have the training and the knowledge that they need to be effective instructors for kids who are at risk. Improving and maintaining high-quality instruction, including classroom management, needs to be an ongoing priority.

What kind of intervention?

Explicit, systematic instruction in the general early years classroom works for everyone, but works twice as well for the at-risk kids (see this research by Barbara Foorman et al). There should be systematic, explicit phonics: teaching the relationship between what words sound like and what they look like. There should also be cumulative practice of skills to automaticity, and work on comprehension. Reading and writing strengths and weaknesses should be monitored, and intervention adjusted accordingly.

If you are including all these elements and collecting data towards your benchmark, and making good progress, then you should just continue until students achieve the benchmark.

Research by the late Carol Connor suggests decoding/word level intervention is about four times more effective in a small group (3 or 4 children per teacher) than a large group, as long as the groups are well matched and managed. This makes sense, as in phonics lessons, teachers have to listen closely to each child, and notice and correct their errors. There’s no evidence that individual phonics instruction is better than this kind of well-matched small group work (click here for information about upcoming Spelfabet holiday groups). The best indicator of which kids should be grouped together is their reading fluency.

Meaning-based instruction, on the other hand, can be done equally well in small or large groups. For English Language Learners, quality of instruction seems to make more difference than language of instruction.

Myths about dyslexia

Dyslexia is not a gift. The myth that people with dyslexia have special talents might result from individual differences and the natural orientation of development towards strengths.

People with dyslexia don’t see letters backwards. As we learn to read, we see mirror images of words in both sides of the brain, which gradually lateralises to the left side of the brain. This happens more slowly in people with dyslexia.

Other myths include: that coloured lenses or overlays help with reading; that dyslexia is a reading comprehension problem; that it’s rare; that people grow out of it; that Brain Training programs not involving reading instruction work; and that improving home literacy will overcome dyslexia. See the blue box on the right of Fletcher and Vaughn’s interesting article titled “Identifying and Teaching Students with Significant Reading Problems for the full list of 18 myths Dr Fletcher refers to in the podcast.

Thanks a quintillion to Kate Winn and Ontario IDA for this interesting podcast series, I’ll be going through the back catalogue in coming weeks, and just noticed a new 4 March 2024 episode pop up, with Australia’s own Dr Jennifer Buckingham. One for tomorrow’s morning dog walk, methinks.

Ten cheers for our new Children’s Laureate!

0 Replies

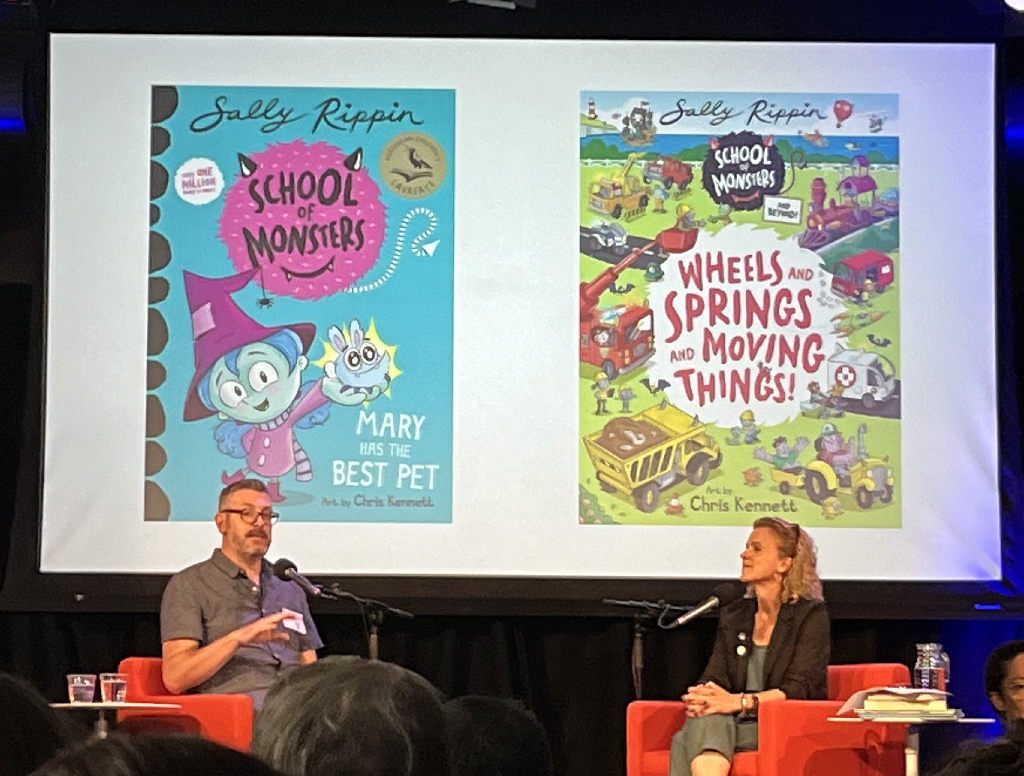

I was so excited to be invited to the launch of Sally Rippin’s two year program as Australian Children’s Laureate on Tuesday, though surprised to spot a former colleague in the crowd who was once staunchly anti-phonics and pro Reading Recovery/Fountas and Pinnell.

Then I realised: Sally is the Perzackly Perfect Person to cheer people off the sinking Balanced Literacy ship (especially since the Grattan Institute’s Reading Guarantee report), and onto ship Structured Literacy, so all kids can hurry up and start enjoying wonderful stories.

Sally isn’t just an author of great kids’ books, she’s the mum of a neurodivergent kid who struggled to read and spell, and a staunch advocate of making sure all kids are taught to crack our spelling code, instead of being encouraged to memorise and guess words. Her book for adults about this, Wild Things: how we learn to read, and what can happen if we don’t, should be in every school and local library. Here she is at the launch with queen of our activist dyslexia mums, Dyslexia Victoria Support founder Heidi Gregory.

Sally’s term as Children’s Laureate is the perfect time for a strong push to dump dross like predictable/repetitive texts and rote-memorisation of high frequency word lists, and promote things like decodable texts and systematic, explicit phonics teaching in Years F-2. It’s also the perfect time to improve early identification and intervention for neurodivergent kids in schools, and knock down barriers to reading for all kids.

The Grattan Institute report (there’s a podcast about it here, and a 20-minute YouTube summary here) says kids with poor literacy currently in school could cost taxpayers $40 billion over their lifetimes, not to mention the personal cost to those kids. I cannot think of a better use of my taxes than ensuring all schools use literacy-teaching methods that are based on the best available evidence, and that struggling and neurodiverse kids whose parents can’t afford high-quality private intervention don’t miss out on it.

At the launch I also got a copy of Come Over To My House, a picture book co-authored by Eliza Hull, full of stories about making the world more accessible for everyone. It’s perfect for our waiting room. I also got some School Of Monsters compilations for our lending library, signed by Sally and illustrator Chris Kennett (who also drew little bats on them). Chris taught everyone at the launch how to draw a monster, which was rather hilarious.

Sally will be travelling all over Australia in the next two years, so make sure you find out when she is coming to a town or city near you (the ACLF newsletter and social media information is here), and spread the word. It’s a story well worth telling.

Benchmark Assessment: often wrong

0 RepliesIt’s the end of the school year in Australia, so children are getting their end-of-year reports.

Many Australian schools use the American Fountas and Pinnell Benchmark Assessment System (BAS) to evaluate reading skills, but a new American Public Media (APM) report says it fails to identify most struggling readers.

If teachers rely on the BAS results, they will be advising many parents not to worry about their children’s reading skills, though there’s good reason to be concerned.

If you’re in this situation, please seek more reliable and valid assessment. Early intervention is highly effective, and ‘late bloomers’ are more likely to wilt and suffer than catch up.

There are plenty of more cost-effective, efficient, reliable, valid literacy skill assessments available for school use. The excellent, Australian Reading Science in Schools website has an assessment list you can download here. Chances are that teachers using the BAS don’t know about researchers’ adverse findings on it, or good alternatives. Do them a favour, send them the APM report and RSS assessment list.

If your school can’t provide valid, reliable reading/spelling assessment, try asking local Speech Pathologists, Educational and Developmental Psychologists or Specialist Educators for a second opinion. Very young kids can do quite a lot of learning in the summer holidays with good professional guidance and/or by attending programs like our holiday groups. The sooner they catch up with peers, the happier they’ll be in 2024.

Help the government improve adult literacy!

0 Replies

The elephant-in-the-room fact that millions of Australian adults have poor literacy skills is back in the news. Radio National’s AM program reports that the government is concerned millions of adults are missing out on jobs, or are ashamed to even apply for work, because they lack basic reading, writing and numeracy skills.

We’ve known about this problem since the 1996 ABS Adult Literacy Survey, but nobody in the adult literacy sector seemed to know what to do about it. Most of their teachers were sold the same Balanced Literacy story (balancing effective and ineffective) at university as other teachers, so that’s not too surprising.

If you cringed through SBS’s Lost For Words, or have browsed the Reading Writing Hotline website, you already know the adult literacy sector hasn’t really kept up with reading/spelling research. The RWH website’s “Literacy Face To Face” handbook for volunteer adult literacy tutors contains an explanation of how we read which goes beyond the three-cueing nonsense still being taken seriously in far too many schools, saying, “The efficient reader uses four sets of clues…” I kid you not. Section 1, page 4. Read it and weep. The screenshot above is from page 7. I really, truly am quite lost for words.

The Minister for Skills and Training, Brendan O’Connor, has commissioned a study to give the government a clearer picture of where adults lack basic skills. I think it also needs to get a clear picture of what scientific research has discovered about how we actually learn to read and spell, and how well this research is understood and translated into practice in the adult literacy sector. Or not.

If the study assesses adults’ reading and spelling, but not phonological processing skills, it will be about as informative as studying an iceberg by examining the part sticking out of the water, while ignoring the part under the water, holding it up (or not). If you’d like to tell the people designing the research this, or anything else, click here and do it before April 24th.

The Chief Executive of the Australian Industry Group, Innes Willox, says basic skill shortages are a national crisis for employers. In their 2021 survey of over 300 employers, 99% said that they’d been disadvantaged in some way because of basic skill shortages among current or prospective staff.

The Chief Executive of the National Apprentices Employment network says an apprenticeship is not a training program in literacy, numeracy or digital skills, and good candidates are missing out because they lack foundational skills.

There’s no shortage of heavyweights who know we have a serious adult literacy problem. I wish we could be confident there were plenty of people in the adult literacy sector offering serious, evidence-informed solutions. The solutions will probably have to come from outside the sector, from people like the readers of this blog. Please, go for it!