Dyslexia facts, myths and strategies

0 Replies

I’ve just listened to a great Ontario IDA Reading Road Trip podcast, in which the IDA’s Kate Winn interviews Dr Jack Fletcher about dyslexia facts, myths and strategies. Click here to listen to the whole thing yourself, and/or read the transcript, which includes references. For the time-poor and my own learning, here’s what I thought were key takeaways.

Defining and diagnosing dyslexia

Dyslexia is a word-level reading and spelling problem which results from a combination of biological and environmental factors. It’s a persistent inability to respond to the kind of explicit, intensive, instruction that works for most people.

Instructional response is the most important criterion for diagnosing anyone with a Specific Learning Disorder, especially dyslexia. Diagnosis should be based on multiple criteria, including progress monitoring measures from intervention, and norm-referenced achievement testing. Specialist dyslexia assessment tools aren’t helpful or necessary. Cognitive tests are only useful in identifying kids who are at risk in the first two years of schooling. After grade two, assessment should be focussed on academic measures of reading, spelling, and writing.

It’s not valid to diagnose dyslexia based on a discrepancy between cognitive skills and academic performance. Kids with reading problems with high and low IQs have the same difficulties with phonological awareness, rapid naming and so on. IQ tests have racial and social bias, so there are social justice issues associated with their use. A Pattern of Strengths And Weaknesses model is also a discrepancy model, is typically inaccurate and grossly under-identifies kids with learning disabilities. We also need to be aware of English Language Learners when identifying at-risk kids, so they’re not misidentified.

Related/co-occurring difficulties

Other kinds of learning disorders and difficulties often co-occur with dyslexia, such as problems with writing or mathematics. Kids with dyslexia often also have difficulties with attention and/or language needing separate intervention. Stimulant medication can help a child pay attention but it won’t teach them how to read. Learning to read words doesn’t guarantee you’ll know what they mean.

About 25% of kids with dyslexia have clinical levels of anxiety. Anxiety predicts a poorer response to intervention, so one US expert, Sharon Vaughn, has introduced five minutes of mindfulness meditation at the start of intervention sessions, to reduce anxiety.

Psychiatrist Shepherd Kellam studied an approach which prevented behaviour problems, but found this didn’t help kids improve their reading. So he introduced a reading intervention, and found that when they became better readers, the girls were less depressed and the boys were less disruptive. He also found that kids all knew who was struggling with reading, and that this was a source of anxiety.

Can dyslexia be prevented?

Many severe reading problems can be prevented if kids get the right kind of explicit instruction and reading experience in their first three years of schooling. About 40% of kids find it hard to learn to read well without really explicit and fairly intense instruction and early reading experience. This makes them aware of the sounds in spoken words and helps them grasp the idea that these sounds are what letters represent (the alphabetic principle) and develops their brains as mediators of reading. Early access to print gives the brain the kind of visual experience it needs to become an automatic reader.

If kids don’t learn to read in the first three years of schooling, it’s very hard for them fully develop their neural system and get the reading experience and vocabulary they need to become skilled, automatic readers. They can be taught to decode, but end up with persistent reading problems. Intervention in first and second grade is twice as effective as intervention after the third grade. It’s hard to differentiate reading problems due to biology and those which are due to environment. Brain scans of third grade poor readers who were not taught well and third grade poor readers at biological risk of dyslexia look the same.

Poor instruction is unfortunately still quite common, though teachers are not to blame, they always have good intentions. They just may not have the training and the knowledge that they need to be effective instructors for kids who are at risk. Improving and maintaining high-quality instruction, including classroom management, needs to be an ongoing priority.

What kind of intervention?

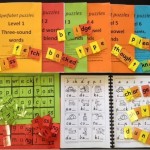

Explicit, systematic instruction in the general early years classroom works for everyone, but works twice as well for the at-risk kids (see this research by Barbara Foorman et al). There should be systematic, explicit phonics: teaching the relationship between what words sound like and what they look like. There should also be cumulative practice of skills to automaticity, and work on comprehension. Reading and writing strengths and weaknesses should be monitored, and intervention adjusted accordingly.

If you are including all these elements and collecting data towards your benchmark, and making good progress, then you should just continue until students achieve the benchmark.

Research by the late Carol Connor suggests decoding/word level intervention is about four times more effective in a small group (3 or 4 children per teacher) than a large group, as long as the groups are well matched and managed. This makes sense, as in phonics lessons, teachers have to listen closely to each child, and notice and correct their errors. There’s no evidence that individual phonics instruction is better than this kind of well-matched small group work (click here for information about upcoming Spelfabet holiday groups). The best indicator of which kids should be grouped together is their reading fluency.

Meaning-based instruction, on the other hand, can be done equally well in small or large groups. For English Language Learners, quality of instruction seems to make more difference than language of instruction.

Myths about dyslexia

Dyslexia is not a gift. The myth that people with dyslexia have special talents might result from individual differences and the natural orientation of development towards strengths.

People with dyslexia don’t see letters backwards. As we learn to read, we see mirror images of words in both sides of the brain, which gradually lateralises to the left side of the brain. This happens more slowly in people with dyslexia.

Other myths include: that coloured lenses or overlays help with reading; that dyslexia is a reading comprehension problem; that it’s rare; that people grow out of it; that Brain Training programs not involving reading instruction work; and that improving home literacy will overcome dyslexia. See the blue box on the right of Fletcher and Vaughn’s interesting article titled “Identifying and Teaching Students with Significant Reading Problems for the full list of 18 myths Dr Fletcher refers to in the podcast.

Thanks a quintillion to Kate Winn and Ontario IDA for this interesting podcast series, I’ll be going through the back catalogue in coming weeks, and just noticed a new 4 March 2024 episode pop up, with Australia’s own Dr Jennifer Buckingham. One for tomorrow’s morning dog walk, methinks.

Leave a Reply