What helps kids read and spell multisyllable words?

19 RepliesVirus rules permitting, the Spelfabet team will present a workshop at the Perth Language, Learning and Literacy conference on 31st March to 2nd April this year.

The title is “Mouthfuls of sounds: Syllables sense and nonsense”, so I’m now scouring the internet for research on how best to help kids read and spell multi-syllable words.

Teaching one-syllable words well seems to be going mainstream

Lots of people seem to have now really nailed synthetic phonics, and are using and promoting it in the early years and intervention (yay!). It’s become so mainstream that I just bought three pretty good synthetic phonics workbooks (Hinkler Junior Explorers Phonics 1, 2 and 3) for $4 each at K-Mart (in among quite a lot of dross, but it’s a start).

Many synthetic phonics programs and resources focus mainly on one-syllable words, most of which only contain one unit of meaning (morpheme), apart from plurals like ‘cats’ (cat + suffix s), past tense verbs like ‘camped’ (camp + suffix ed), and words with ancient, rusted-on suffixes like grow-grown and wide-width.

Multisyllable words contain extra complexity

Synthetic/linguistic phonics programs which target multisyllable words, including spelling-specific programs, vary widely in their instructional approach. Multisyllable words aren’t just longer (in sound terms, though words like ‘idea’ and ‘area’ are short in print), they contain extra complexity:

- Most contain unstressed vowels. When reading by sounding out, we apply the most likely pronunciation(s) to their spellings, often ending up with a ‘spelling pronunciation’ that sounds a bit like a robot, with all syllables stressed. We then need to use Set for Variability skills (the ability to correctly identify a mispronounced word) to adjust the pronunciation and stress the correct syllable(s).

This can mean trying out different stress patterns, and sometimes also considering word type – think of “Allow me to present (verb) you with a present (noun)”. Homographs often have last-syllable stress if they’re verbs, but first syllable stress if they’re nouns.

- Prefixes and suffixes change word meaning/type, they don’t just make words longer e.g. jump (simple verb), jumpy (adjective), jumped (past tense/participle), jumping (present participle), jumpier (comparative), jumpiest (superlative), jumpily (adverb), and the creature you get when you cross a sheep with a kangaroo, a wooly jumper (agent noun, ha ha). I write ‘wooly’ not ‘woolly’ (though both are correct), because it’s an adjective not an adverb: wool + adjectival ‘y’ suffix, as in ‘luck-lucky’ and ‘boss-bossy’, not wool + adverbial ‘ly’ suffix, as in ‘real-really’ and ‘foul-foully’.

- Word endings often need adjusting before adding suffixes: doubling final consonants (run-runner), dropping final e (like-liking) and swapping y and i (dry-driest). Kids need to learn when to adjust, and when not to, so they don’t over-adjust and end up with ‘open-openning’, ‘trace-tracable’, and ‘baby-babiish’.

- Co-articulation (how sounds shmoosh together in speech) often alters how morphemes are pronounced when they join – compare the pronunciation of ‘t’ in ‘act’ and ‘action’. Sometimes this also results in spelling changes e.g. the ‘in‘ prefix in ‘immature’, ‘imbalance’, ‘impossible’ (/p/, /b/ and /m/ are all lips-together sounds), ‘illegal’, ‘irrelevant’, ‘incompetent’ and ‘inglorious’. ‘In’ is pronounced ‘ing’ at the start of words beginning with back-of-the-mouth /k/ and /g/, like the ‘n’ in ‘pink’ and ‘bingo’.

- Reading longer words requires a lot more trying-out different sounds, particularly flexing between checked and free (or ‘short/long’) vowels, as in cabin-cable, ever-even, child-children, poster-roster, unfit-unit. Vowel sounds in base words often change when suffixes are added, e.g. volcano-volcanic, please-pleasant, ride-ridden, sole-solitude, study-student, south-southern (word nerds, look up Trisyllabic Laxing for more on this).

- Many word roots, like ‘dict’, ‘spect’, ‘fract’ and ‘path’, aren’t English words in their own right, but still mean something. However, teaching morpheme meanings may not have much benefit for decoding, fluency, or even vocabulary or comprehension (see Goodwin & Ahn (2013) meta-analysis of morphological interventions).

- Spellings that look like digraphs sometimes represent two different sounds in different syllables e.g. shepherd, pothole, area, stoic, away, koala (see this blog post), again requiring flexible thinking about how to break words up.

I use the Sounds-Write strategy to help kids read and spell multisyllable words, which doesn’t teach spelling rules, syllable types, or other unreliable, wordy things. The Phono-Graphix and Reading Simplified approaches are similar.

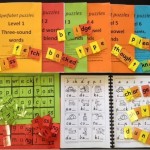

However, Sounds-Write doesn’t have an explicit focus on morphemes (well, maybe their new Yr3-6 course does, I haven’t done that yet), so I’ve also been using various morphology programs and resources: books by Marcia Henry, Morpheme Magic, games like Caesar Pleaser and Breakthrough To Success, Word Sums, the Base Bank, and the Spelfabet Workbook 2 v3 for very basic prefixes and suffixes. However, I need a better grip on the relevant research and its implications for practice.

Video discussion on syllable issues

There’s an interesting video of a discussion about research on syllable issues between Drs Mark Seidenberg, Molly Farry-Thorn and Devin Kearns (you might know his Phinder website) on Youtube, or click here for the podcast.

I always want to shout “Speak up, Molly!” when watching these discussions, because she doesn’t say much, but what she does say is usually great. Near the end of this video, she summarises the implications for teaching. Here’s my summary of her summary:

- Explicit teaching about syllable types takes time, adds to cognitive load and takes kids out of the process of reading, so try to keep it to a minimum in general instruction.

- Children who aren’t managing multisyllable words after general instruction may need to be explicitly taught vowel flexing, and/or about syllable types.

- Group words in ways that make the patterns/regularities and clear, and help children practise vowel flexing.

- It can be helpful for teachers to know a lot about syllables, rules etc, but that doesn’t mean it all needs to be taught.

Dr Kearns then goes further, saying he suggests NOT teaching syllable types and verbal rules, apart from basic things like ‘every syllable has a vowel’. Instead, he recommends demonstration of patterns and then lots of practice. Many children with literacy difficulties have language difficulties, so verbal rules can overwhelm/confuse them, and aren’t necessary when skills can be learnt via demonstration and practice.

I’m now trying to get my head around his research paper How Elementary-Age Children Read Polysyllabic Polymorphemic Words (PSPM words) without getting too overwhelmed/confused by terms like ‘Orthographic Levenshtein Distance Frequency’, ‘Laplace approximation implemented in the 1mer function’ and BOBYQA optimization’, and having to go and lie down.

The 202 children studied were in third and fourth grade, attending six demographically mixed schools in the US. This was quite a complex study with multiple factors and measures, so I won’t try to summarise the methods and results, but instead skip to what I think are the main things it suggests for teaching/intervention (but please read it yourself to be sure):

- Strong phonological awareness helps kids read long words, though it may make high-frequency words a little harder, and low-frequency words a little easier. It may help kids link similar sounds in bases and affixed forms, e.g. grade-gradual.

- Strong morphological awareness also helps kids read long words. It’s more helpful than syllable awareness. Processing a whole morpheme is more efficient than processing its component parts, and since morphemes carry meaning, they may help with vocabulary access.

- It helps to know sound-spelling relationships and how to try different pronunciations of spellings in unfamiliar words, especially vowels.

- Having a large vocabulary helps too, as children are more likely to find a word in their oral language system which matches (more or less, via Set for Variability) their spelling pronunciation. Children with large vocabularies might also persist longer in the search for a relevant word.

- High-frequency long words, and words with very common letter pairs (bigrams), are easier to read than low-frequency words and ones with less common letter pairs.

- Most kids learn to process morphemes implicitly in the process of learning to read long words, but struggling readers have more difficulty extracting information implicitly, so many need to be explicitly taught to do this. Strategic exposure and practice is more likely to produce implicit statistical learning than teaching rules, meanings etc.

- It’s easier to process base words that don’t change in affixed forms (e.g. appear-appearance) than ones that change a bit (e.g. chivalry-chivalrous). Kids with weak morphological awareness may need to be taught awareness of both.

- Knowing many derived words’ roots (e.g. the ‘dict’ in ‘contradict’, ‘predict’, ‘dictionary’, ‘dictate’, ‘addict’, ‘valedictory’, and ‘verdict’) makes it more likely the reader will be able to use root word information to read long words.

- Knowledge of orthographic rimes doesn’t seem to help kids read long words. Kearns calls these ‘phonograms’: the vowel letter and any consonant letters following it in a syllable e.g. the ‘e’ and ‘ict’ in ‘predict’, or the ‘uc’ and ‘ess’ in ‘success’.

- This study focussed on reading accuracy but not fluency, and didn’t measure prosodic sensitivity or Set for Variability skills. Further research is needed on these.

If you have insights on any of the above, please write them in the comments below.

Alison,

I’m so glad to hear you will be doing a workshop on this important and timely topic!

– Words with more than one syllable are common in English, even in books and passages for beginning readers. For example:

– On a popular 1st-grade progress test (DIBELS), 24% of the words have two syllables.

– For all grade levels, including 1st grade, the vast majority of words on Lexile® WordLists (taken from grade-level curricular materials) are multisyllabic. In fact, of the 34 words on the 1st-grade list, only 6 have one syllable and 28 are multisyllabic. Examples include:

– 1st-grade words: “lesson”, “model”, “topic”, “sentence”

– 2nd-grade words: “event”, “effect”, “analyze”, “relate”

While words with more than one syllable predominate in curricular materials, as indicated below, they do present a hurdle for beginning readers and spellers. Thus, explicit instruction in how to decode and spell multisyllablic words would seem to be indicated.

One thing that makes reading multisyllable words difficult is that most of them have at least one unstressed syllable. The (schwa) vowel in an unstressed syllable sounds weak and is not pronounced clearly. Schwa is the most frequent speech sound in English so it is not surprising that research has demonstrated that raising awareness of syllable stress improves reading skills, even in beginning readers. In his landmark book on English orthography, Venezky (1999) said that schwa is “the most difficult sound to predict in the entire orthographic system”. (p. 62) Subsequent research has suggested that words containing at least one schwa are more difficult for both adults and children to represent accurately in a stored mental lexical (Edwards. et al., 2021; Ocal & Ehri, 2017). Further, Lin et al. (2018) found, “… stress sensitivity accounted for unique variance in 6-year-old children’s word reading over and above oral vocabulary, phoneme sensitivity or phonemic awareness. This finding adds to a growing body of research showing the unique importance of prosodic sensitivity in reading development over and above sensitivity to segmental phonology.” They found that stress perception was more difficult than phoneme perception, even for adults. These authors suggest “… children’s stress sensitivity generally develops at a slower pace than their phoneme sensitivity” and that “increased exposure to written words in early school years does not benefit the development of stress sensitivity to the same extent as it does to the development of phoneme sensitivity”, perhaps because stress is not explicitly marked in English orthography. They speculated that “more years of reading experiences may be necessary in order for the benefit provided by print exposure to have an effect on the efficiency of activating stress representation of words in the mental lexicon.” These authors concluded, “Instructional activities that can strengthen young children’s implicit and explicit sensitivity of stress may result in important gains on improving reading abilities.”

As you pointed out, in the phonics programs that do include syllable and syllable stress concepts, the order of introduction is typically after most of the letter-sound concepts, with some curricula delaying explicit instruction of multisyllabic words “for a year or more” (Seymour, 1997). Given the ubiquity of multisyllablic words in reading materials for elementary school children and to be consistent with the principle of explicit instruction, it seems reasonable to introduce multisyllabic word concepts fairly early in a scope and sequence. In addition, consistent with the principle that recognition is easier than recall, an initial focus on recognizing (identifying) unstressed syllable(s) in multisyllabic words would be reasonable. This is a difficult concept so students are likely to need prolonged review and practice recognizing unstressed syllables and decoding words with unstressed syllables before they are ready to learn strategies for recalling the spelling of unstressed schwa vowels.

In the Lexercise Structured Literacy Curriculum™, syllable stress concepts are introduced beginning at Level 4, just after the student has covered the basic consonants and the five short vowels in closed syllables. At every subsequent level new orthography & morphology concepts are introduced and practice is provided with those elements, first in single-syllable words and then in multisyllable words.

You might be interested in this article by Devin Kearns and his Ph.D. student Tori Whaley, a long-time Lexercise Teletherapist:

– Helping Students with Dyslexia Read Long Words: Using Syllables and Morphemes (https://86d0fd32-d4e3-4e59-8832-40b7b4535920.filesusr.com/ugd/0edac4_c5bfd89beec14e96bc7139ee868ee88d.pdf)

Good luck with this workshop!

My best,

Sandie

Wow, thankyou, Sandie, for the nice feedback and all that very useful information. I am printing out the Kearns/Whaley article now, and trying to get my head around the difference between prosodic sensitivity and syllable awareness, maybe the world of poetry has something to offer regarding this? Maybe studying poems and learning to write verse in iambic pentameter builds prosodic sensitivity? I have a friend who is a poet and English teacher so I might ask his perspective on this, as well as searching Google Scholar for the relevant research. All the very best, Alison

Deepening my understanding about morphology as the organising and structural component of our orthography has been an absolute game changer for me and my students. Some of the concepts that I find particularly helpful include that

1. graphemes and orthographic markers are constrained by morphemic boundaries

2. words that share a base, share meaning and spelling despite pronunciation

3. the 3 suffixing conventions

4. word sums and matrices

Sue Hegland’s book “Beneath the Surface of Words: What English Spelling Reveals and Why it Matters” is a fantastic book that helps to explain how our writing system works.

Thankyou, I’d love to get this book but I have a “don’t buy from Amazon” policy because I have concerns about their employment practices and about Jeff Bezos’s involvement in cryogenics, and in space tourism, which is an absolute disaster for our climate. I’ve asked one of our local bookshops whether they’ll stock it. If not, I’ll contact the author directly. All the best, Alison

I honestly wasn’t aware of those issues, Alison!

I feel like I’m half way to where you are Kylie! Can definitely see how morphology works within the English language and how it impacts orthography etc, but I am at such a loss with how to teach its relationship with phonology and, in particular, how to use it to teach kids when they are first learning to decode 2 syllable words. Feel much more comfortable doing matrices, word sums etc and diving into etymology when working with kids whose reading is pretty good, but they need spelling help.

Jo, I’ve shifted to explicitly teaching phonology within the context of morphemes. I start with adding simple suffixes to a free base without requiring application of suffixing conventions first.

Such a helpful article, and comments. I’m still getting my head around the evolution of intervention traditions in the UK, US and Aus. Do Phono-Graphix, Sounds Write and Reading Simplified have a common ancestor?

At least Phonographix and Sounds-Write are based on the ideas of Prof. Diane McGuinness see https://soundreadingsystem.co.uk/about-the-srs/diane-mcguinness), the author of the classic “Why Children Can’t Read and What We Can Do About It”, and a number of other useful texts about early reading/spelling. She outlines a prototype teaching strategy and these programs both adhere pretty closely to that prototype (Phonographix was created by her son and daughter-in-law, I think). I don’t know about Reading Simplified, but from what I’ve seen of it, it seems pretty close to her prototype. Diane McGuinness has also produced her own materials, the original version was called Allographs and the later version is called Sound Reading System, see https://soundreadingsystem.co.uk. So I guess that might also be considered a descendant of her prototype/ideas. All the best, Alison

Thanks so much for this! My course really only looked at the descendants of the OG approach, so I am interested to follow up on these links. I did the Reading Simplified introduction last week out of interest and liked the focus on all sub-skills being embedded rather than taught and practised separately and the idea of teaching patterns by exposure rather than rules.

Vicky, you might be interested in this blog by Nora Chahbazi (like me, trained in Phono-Graphix) from EBLI (Evidence-Based Literacy Instruction). She also doesn’t emphasize rules.

https://eblireads.com/r-controlled-vowels-how-to-teach-in-a-way-that-makes-sense/

Thank you I’ve found the EBLI blog very useful in the past-good to get more of an overview of how that is linked to this other ‘tradition’ (for want of a better word). I definitely find there are dyslexic students who cannot work from rules at all-they cannot remember and apply the steps necessary-but I have others who are very intellectually curious and like working out the rule. It depends on their overall profile, I suppose. In the end, they all need the multiple exposures so I suppose the decision is whether spending time on the rule is an opportunity cost.

Carmen and Geoffrey McGuinness wrote Reading Reflex and created Phonographix (Geoffrey is Diane McGuinness’s son) and my understanding is that a lot of excellent programmes including Sounds Write, Reading Simplified, ABeCeDarian and Phonics International (Debbie Heppelthwaite) all grew out of Phonographix. I think the creators of these programmes all did the Phonographix course either in person or online through Read America in the nineties, and went on to develop their own very successful programmes. They all use a similar approach. I think Carmen McGuinness sued a group of them at one stage but I don’t know what the outcome was.

Very interesting, thanks Alison! I’m particularly interested in that prosodic sensitivity/syllable awareness distinction. I think we teachers actually hinder kids awareness of syllable stress when using the “clap out the syllables” method of counting syllables. And using language like “syllables are the beats in words” with pictures of drums. If one wants to use analogy to music, syllables are rhythm, and beats are stressed syllables. I have often seen kids get muddled and only clap the stressed syllables. I loved learning the zipped lips method of counting syllables from a Lyn Stone workshop, as it preserves the prosodic pattern of the word. It would indeed be interesting to see research in the future on whether poetry/scanning/chants improve that prosodic sensitivity.

Alison,

The distinction between **lexical stress** (at a word level) and **prosodic stress** (at a phrase or sentence level) is important here.

For teaching decoding and spelling it is mainly **lexical** stress that concerns us. Poetry involves prosodic stress awareness …and much, much more, as well… so I am skeptical that it is the best way for us to **introduce** the concept of syllable stress, although I do think that is how syllable stress is often introduced in English Language Arts curricula.

This fascinating series of studies (pretty deep in the weeds) supports the idea of learning to read as a process of learning about statistical associations between words’ spellings and their phonological forms and of skilled reading as deploying these associations”.

– Treiman, R., Rosales, N., Cusner, L., and Kessler, B. (2020). Cues to stress in English spelling. Journal of Memory and Language, 112.

While I certainly get the point about statistical learning, it doesn’t seem very actionable. But these authors help us see how it is, in fact, VERY actionable – not only by including instruction and practice in syllabication & morphology (suffix types & word stress) but in providing “a great deal of practice”. They conclude, “…well-understood and well-integrated multisyllabic word reading strategies will only be achieved after a great deal of practice.”

– Heggie, L. and Wade-Woolley, L. (2017). Reading Longer Words: Insights Into Multisyllabic Word Reading. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, SIG 1, 2( 2).

This is why I am an advocate of explicitly introducing lexical stress **early** and then providing cumulative review and practice over many months.

Cheers, Sandie

Thanks, Sandie, more gems. I think the biggest barrier to research translation is that clinicians like me, who don’t have a university affiliation, have to pay ~$40 or more to read a journal article relevant to their work. Usually the research they’ve done has already been paid for by the taxpayer and it’s in the public interest that practitioners know about it. Talk about perverse incentives, and thank goodness so many researchers are now making their work publicly accessible. Alison

I could not agree more, Alison!

Information “wants to be free”….and, as you said, it is breaking free. There are so many open source journals now and also free dictionaries (with detailed etymologies) and encyclopedias. Especially with open source information you have to be careful, remember not to believe everything you read, ask yourself if it makes sense and if it is consistent with the wider body of information… and understand the publisher’s motivations and business plan , i.e., follow the money. But that’s true with all sources of information, right?

Wikipedia is an example. Below are a few Wikipedia article on the topic we are discussing (linguistic stress). About a year ago I taught a Lunch n’Learn webinar on issue with teaching multisyllabic words with schwa for Lexercise’s 100+ therapists. I found these articles very helpful in preparing for that webinar….and I hope you do, too!

Stress (linguistics). (7 September 2020). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stress_(linguistics)

Stress and vowel reduction in English. (5 August 2020) In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stress_and_vowel_reduction_in_English

Vowel reduction. (1 September 2020). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vowel_reduction

Thank you so much, Alison, for summarizing the Kearns article. I have found his research to be very helpful, and I also appreciated his appearance on the Mark and Molly Show. However, this piece is a lot longer than the others I’ve read, so it was really helpful to get your quick take.