Don’t waste school PA time on syllables and rhyme

63 RepliesOur education system seems to be abuzz with discussion of the importance of phonological awareness, which is excellent. Most difficulties with reading and spelling English words can be traced back to poor awareness of the sounds in words.

However, I’m worrying that valuable lesson time is being wasted teaching school-aged children awareness of large, salient phonological features like syllables and rhyme, instead of focussing on individual phonemes, the smaller, harder-to-discern sound units represented in our writing system.

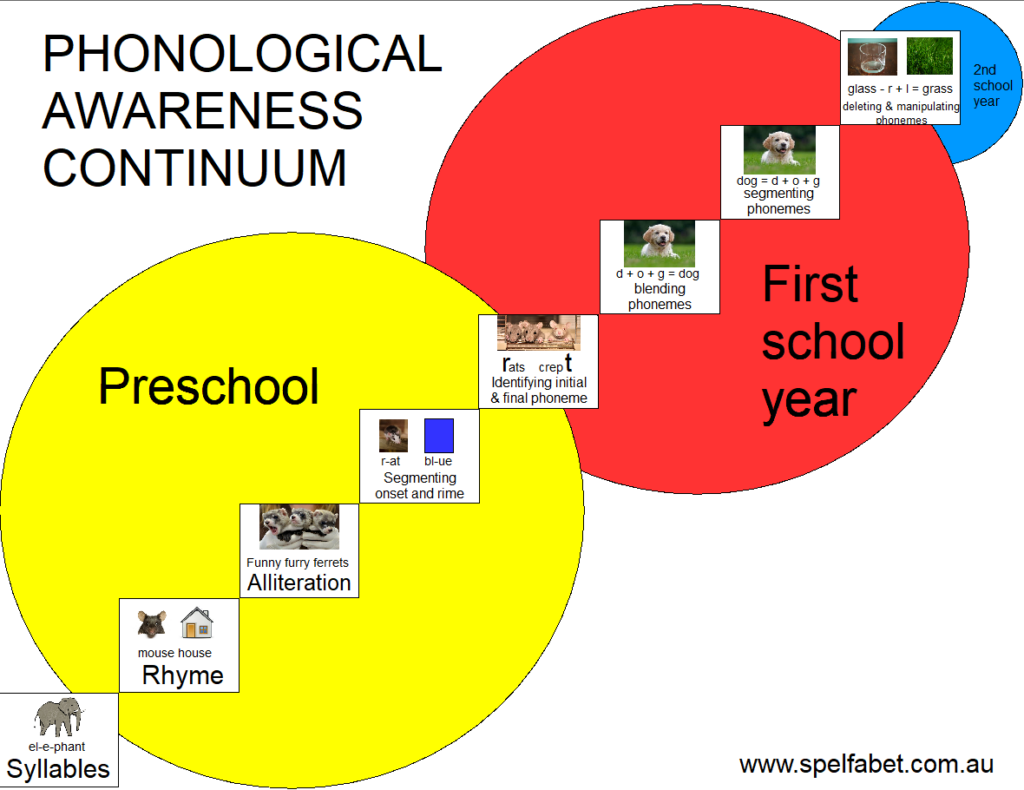

Various versions of the above phonological awareness continuum diagram, minus the circles I’ve added, have been floating around our education system for years, and probably helped foster the common misconception that awareness of syllables and rhyme are prerequisites for developing phonemic awareness. Yes, preschool rhyming skills tend to correlate pretty well with later reading skill, but correlation is not causation.

The Reading League in the US last year published a review of current research on phonemic awareness and phonics by University of Rhode Island Emeritus Prof Susan Brady, which concludes it’s not necessary to devote time and effort to fostering awareness of syllables and rhyme/onset-rime before children can acquire phonemic awareness. You can read the long version here, or a briefer version in their journal. Prof Brady uses the term “phonological sensitivity” for larger-chunks phonological awareness (everything except phonemic awareness).

Phonological sensitivity is evident across cultures, and acts as a mnemonic

Prof Brady writes that, “In cultures not having the benefits of literacy, phonological sensitivity skills have been documented, but not full awareness of phonemes, even by adulthood” (p6, and she refers to this old but interesting study, I guess there now aren’t many non-literate cultures available to study).

Ancient poems, chants and songs from predominantly oral traditions often have strong metrical structure, rhyme and/or alliteration. These are still features of poetry and song around the world, though admittedly my research on this has only been via travel, our excellent local Boite World Music events, WOMADelaide, and reading internet articles with titles like “9 Countries Whose Traditional Forms of Poetry You Didn’t Know About”.

As well as being integral to art forms, these phonological features make information easier to remember and transmit verbatim. The Iliad might have been lost to an ancient game of Biddelonian Whispers without its strict metrical structure. Beowulf might have drifted and dissolved into diverse dreadful dramas, and I doubt we’d remember the words of our favourite songs so exactly if they were written in free verse.

Phonemes are more difficult to discern, but are also powerful mnemonics

Phonemes are invisible and transient, and blur together when we speak in a process called coarticulation, making them hard to separate out. There’s no reason to be aware of phonemes unless you’re learning an alphabetic writing system.

Dr Linnea Ehri chaired the US National Reading Panel’s investigation of phonological awareness 20 years ago, and has been a leading researcher on phonemic awareness since then. I love her analogy of the phonemes in spoken words holding the “glue” needed to hold written words in memory. When children become aware of phonemes, they activate the glue. You can hear Dr Ehri talk about this from the 60 minute mark of this Reading League podcast, I’m sure you’ll then want to listen to the whole thing.

Dr Ehri explains that teaching children to say words slowly, listening for their sounds, and thinking about their mouth movements, builds phonemic awareness. It’s highly effective to use letters to represent sounds in phonemic awareness activities, as this makes the relevance/purpose of the activity clear and transferable, but representing sounds with tokens (buttons, shells, gemstones, banana chips, whatever) is also effective, for example with children who don’t yet know letters. Dr Ehri doesn’t talk about handwriting in this podcast, but I’m sure she would agree that saying words’ sounds while writing their spellings is also a powerful word-glue-activating activity.

This phonemic awareness continuum is seriously underspecified

If you look at the phonemic awareness steps in a typical phonological awareness continuum diagram, they’re not very informative. For a start, there aren’t many of them for such a complex and difficult process. Blending usually appears before segmenting, though these are reciprocal processes, and should be taught and learnt as such.

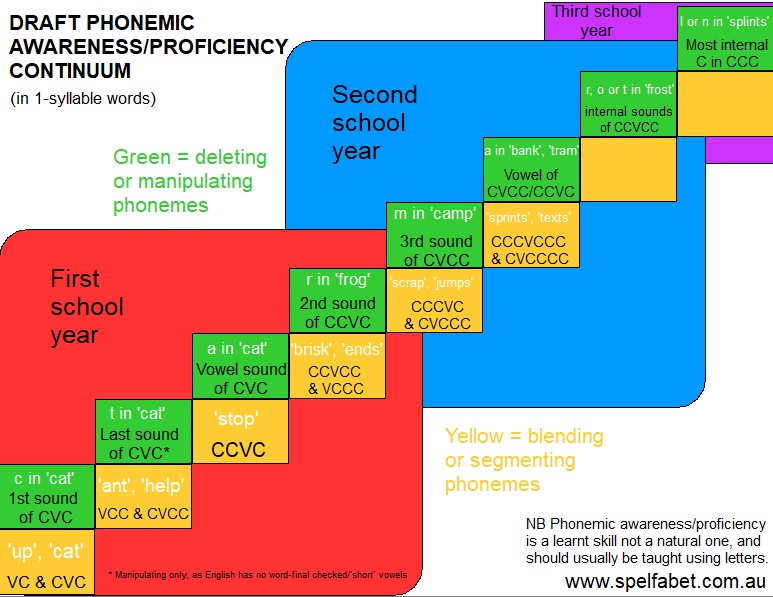

There’s also no useful detail on word types, though it’s obviously easier to blend and segment a word with three sounds, like ‘cat’, than it is to blend and segment a word with seven sounds, like ‘scripts’. It’s easier to delete or manipulate a single initial phoneme, like the ‘c’ in ‘cat’, than it is to delete or manipulate the ‘c’ in ‘scripts’. I’d also expect the average six-year-old to find it harder to blend/segment the word ‘scripts’ than to delete/manipulate the first sound in ‘cat’, so deletion/substitution aren’t always the hardest phonemic awareness activities. It all depends on phoneme identity, order and number.

If we represent vowels with V and consonants with C, then list all the possible combinations of these in single syllable words in English, putting example words in brackets, the list goes something like this: V (eye/I), VC (up), CV (go), CVC (hot), VCC (elf), CCV (stay), CVCC (help), CCVC (stop), CCVCC (crust), VCCC (ends), CCCV (spree), CVCCC (tents), CCCVC (strayed), CCVCCC (frosts), CCCVCC (splint), CCCVCCC (sprints) and CVCCCC (texts). These should be represented on the phonemic awareness continuum.

In general, it’s easiest to discern the first sound in a word, then the last sound, and then sounds that are in the middle. Internal consonants are especially hard to discern, which is why young children often write ‘stop’ without the ‘t’ and ‘help’ without the ‘l’. They blur into the sounds around them and get a bit lost. Sound type can also make a difference, for example the sounds /r/ and /l/ have vowel-like qualities, so sometimes children consider them part of the vowel.

I’d like to propose the above as an interim replacement for the less-helpful phonological awareness continuum diagrams currently floating around our education system. I’m sure people smarter than me (perhaps you?) can and will improve on it.

Nothing against syllables and rhyme for preschoolers, in fact I am planning to enjoy lots of them with my three preschool neighbours when our COVID Lockdown 6.0 finally lifts. But school-aged children need to activate their remembering-written-words glue by focussing on phonemes.

A great message! We are needlessly slowing down children from accessing the code with the mistaken belief that global PA is the necessary prerequisite to phoneme awareness, as you say. I hope many people will find this article and share it.

On your last minor point, I have a different experience, however. Reading Simplified teachers find segmenting and manipulating at the 5 and 6 sound word level quite common in the first year of school mostly because of an emphasis on a word chaining activity we call Switch It. I don’t know of studies that test that directly however.

Thanks again for this post and all your other great teaching and resources.

Wow, Marnie Ginsberg likes my blog post, I must be doing something right. Thanks so much for the lovely feedback! I’m a speech pathologist and the majority of my caseload has additional difficulties (ASD, ADHD, intellectual disability, language disorder) as well as word-level learning difficulties, so I am not really the best person to say what the average mainstream child should be able to achieve in a given timeframe. Some of my kids astonish me with how quickly they grasp PA and can start manipulating, reading and spelling CCVCCs and CCCVCs/CVCCCs etc, I had one little girl recently who was out of the blocks and able to do this in a couple of sessions (I do what you call Switch It, but I’ve been calling it word-building and changing, while some other people call it Word Chains, and there are probably other terms, we should standardise that sometime). My diagram is just a draft to try and relegate phonological sensitivity to preschool, tease out the steps, and encourage early years teachers to incorporate them in their goals. Let’s hope that your experience will soon be the experience of all educators, and more of the steps will end up in the first year of schooling, as more and more kids get off to a flying start because they have great phonemic awareness. All the very best, Alison

Haha! I would have thought the same about you even recognizing MY name. Very kind. I really do read or watch almost everything I see of yours because I know it will be good stuff.

Yes, I don’t think it’s a mainstream accomplishment yet. I just wanted to point out that it’s a possibility with activities like word chaining or whatever one calls it. For my previous program, the Targeted Reading Intervention–I called it Change One Sound. At that time, I didn’t know others beside Phono-Graphix were doing anything that put the burden on the child to manipulate letter-sounds. I’m glad it’s catching on, by whatever name.

For my previous program, the Targeted Reading Intervention–I called it Change One Sound. At that time, I didn’t know others beside Phono-Graphix were doing anything that put the burden on the child to manipulate letter-sounds. I’m glad it’s catching on, by whatever name.

It makes sense that you would see those with more profound language challenges–early on–than I do as a reading tutor. I do have young kids referred to me for sure, but the bulk of my students over the years have been 2nd-4th graders. So when I see a 5 year-old, they may be less likely to have a language issue (other than run-of-the-mill poor PA). Either way, I hope researchers will start to test a word chaining activity, in isolation, like Phono-Graphix brought to my attention, so we’ll have better data about what’s possible. Thanks for taking the time Alison!

I thought you might like this piece Marnie! A student I have been working with for just 2 days was able to read two books on the sounds she is working on at the age of 11 at a Kindy level. She said to a staff member today and her Mum, I want to learn to read! Such effectiveness of showing the code! Once they see the patterns and (get it!), they just fly! Thanks Ladies, truly!

Wow thanks Alison – this articulates and makes sense of something that has been gnawing away at the back of my mind this year. Love your work!

Thank you!

How does this fit in with Kilpatrick’s work? Does this make the PAST test redundant?

Absolutely not, I think the PAST test is very useful, but I think most school-aged kids with reading and spelling difficulties can pass the syllable and rhyme sections, and only start to have difficulties at level H, where they have to drill down to the phoneme level and split up an onset into two phonemes. I also think that we have to think strategically about how to make best use of lesson/session time, and oral-only phonemic awareness tasks might not be as effective as ones that represent sounds with letters, but you don’t need a lot of preparation or materials to do oral-only PA, you can keep the one-minute activities in your handbag or on your phone and do a set while you’re waiting for the bus, and if you can do ten phoneme deletions or substitutions in oral-only format with the whole class, but only five with letters (because you have to get them out, find the right ones, find the one that’s dropped on the floor etc) and only one kid at a time comes to the board to do them, while everyone else watches, there’s an efficiency and effectiveness and active participation tradeoff that I think needs to be considered. There isn’t just one way to activate the glue on phonemes, and doing it just one way can get kind of boring. Hope that makes sense, Alison

Thank you for your response and your post. Really important conversation.

I think this is great, however what would you say for children who have global developmental delays, would you start earlier on the continuum than where they are at agewise. Or what about older children who cannot ‘hear’ the first and last sounds, would you backtrack then to syllble level segmentation/blending or just aim to explicitly teach it at phoneme level?

I tend to spend a few minutes on a phonological awareness ‘warm up’ before I jump in to explicit phoneme level teaching and then send home some Phonological awareness practice (as the pre-req skill set a few levels before my instructional level). E.g I might be working on continuant CVC spelling e.g. mat/sat and send home some rhyming tasks that are oral/aural based and errorless learning.

Hi Beck, I have worked and currently work with quite a few kids with IQs in the 50s and 60s and I’ve taken the same phoneme-based approach as with everyone else, but with very tiny steps and more repetition. If you think about working on onset-rime in CVC words with single-phoneme onsets, its the same thing as manipulating the initial phoneme, so that’s the bridge from phonological sensitivity to phonemic awareness, and that’s where we start. But if you focus only on onsets, they think that the first sound is the only sound in the word (especially if they’ve been taught to look at the first letter and guess), so it’s important to quickly get them listening for final consonant and then vowel, and writing CVC words saying all the sounds. That’s the reason behind my Workbook 1 format – take a small number of phonemes, read and write them in all relevant word positions, and then add a few more, while at the same time doing word sequences, games and using decodable books with the same phoneme-grapheme correspondences, to really nail each PGC down. I think working at too many levels (syllable, onset-rime, phoneme) can really confuse these kids and it’s better to stick to phonemes. Everyone builds their reading brain the same way, it’s just a lot harder when you have an intellectual disability. Hope that makes sense, Alison

thanks, that makes a lot of sense and really helps with what I am working on with some of clients.

Thank you! Great advice.

Wow! What a very informative and pragmatic piece. Great as always, Allison.

Love what you have created as ‘SOR purists’ are getting hooked up with rhyme, syllables, floss rule etc etc. Or … basically throwing M S V surplus out but replacing it with new rules which seems to me to be the new overload!

Yeah, Rules Shmules, I say. I don’t find talking about open and closed syllables, the floss rule, etc etc, as helpful as just giving examples and lots of writing and reading practice, always saying the words aloud. A lot of stuff that’s done in the name of phonics and morphology is surplus to requirements. You don’t really need verbal, jargon-filled rules to do statistical learning. Alison

Amazing! Except for the fact I work at a school where there is a 90% EAL population who due to Covid missed 4 year old Kinder and much of Prep/Foundation. Many can’t “clap” their name (syllabification). ToPALL screening shows only about 10% hit age appropriate scores. Many kids are at least 1 year behind the expectations of the Victorian curriculum.

So sorry to hear that, the pandemic has been such an educational nightmare for disadvantaged kids. I don’t think it matters too much that kids can’t clap their names on school entry, though. The main thing is whether children understand that words are made of sounds and are linking these sounds to graphemes, and have plenty of decodable text to provide them with reading practice to automatise each pattern. If your clients are working online, might some of our freely-accessible wordwalls be useful to them? https://wordwall.net/teacher/666616/spelfabet/folder/116471/1-initial-code-units-1-10. I guess you also know Little learners apps are currently free online, since you’re using the ToPALL. But maybe the kids at your school don’t have ipads. Anyway it sounds like you’re right onto all the things that will help the students at your school, so I hope that soon everyone will be vaccinated and we can really get down to the serious business of helping the tiny people who have missed out on so much in the last couple of years catch up.

Ah…I am new to the school starting in Term 3 this year. Most of the kids are at home without input based on prioritisation of technology to older kids. I have only assessed half of the Prep and Grade 1 with the Topall with some sobering findings. It is a school with rigorous adherence to LLi and RR and no current plans for systematic phonics in sight. Thanks for the resources and ideas. Wish me well!

Sorry – as Admin can you please retrospectively amend my identity to initials or first name?

This is amazing! Thank you for taking the time to write it!

With the above, just wondering how this fits with with Dr Kilpatrick’s PA program and whether and the role of syllables and onset-rime for manipulation tasks?

Thanks! I actually don’t use the syllable or rhyme based One Minute Activities, as I am yet to find a kid who can’t do them once they understand the task, apart from very orally dyspraxic kids without the necessary motor planning. They probably exist somewhere, but they must be very low-incidence. We do the CTOPP as a baseline activity when we first see kids, and unless they’re really tiny, they can do the syllable and onset-rhyme tasks in the elision subtest, but not manipulate e.g. the /n/ in ‘snail’. So I usually start with Level H. Whenever possible I prefer to work on PA with letters, but session time is always ticking away and it’s quite hard to do ten manipulations in under a minute with graphemes, there’s often a bit of faffing around finding the right ones, scanning the array to find one that’s actually right under your nose, etc. Working online makes that even harder, I’m still trying to find the perfect moveable alphabet for use on telehealth. I also see quite a few kids who are 100% focussed on the LOOK of words and 0% focussed on their sounds, and I find that taking the letters away forces them to think about sounds. OK, the research says it’s not AS EFFECTIVE as working with letters/spellings, but it is still effective, and if you can do ten oral-only activities in a minute but only five with-letters activities, you have to weigh up efficiency and effectiveness. I think Linea Ehri’s message is that any activity which teaches kids to combine, separate and manipulate phonemes helps activate the glue which holds written words in memory, and there isn’t just one right way to do this. I hope that makes sense. All the best, Alison

I actually have a few students who are in older primary school who cannot rhyme and cannot hear syllables, would you still just go in at the phoneme level for these students as well?

Yes, I know a few kids like that, and without knowing them myself (and you do, so please if you think I’m wrong just ignore me and trust your own judgement, I can’t give proper professional advice for kids I’ve never met) I’d say don’t worry about syllables and rhyme, they aren’t the units represented in our writing system. Just work on phonemes and representing them with graphemes, and word-building with suffixes, compounds, prefixes and then more complicated bases and the unstressed vowel (say it as it’s spelt). We use the teaching sequence in the Phonic Books a lot with older kids because the books are more age-appropriate than most decodables, but maybe you have other resources that are suitable for your clients, it’s quite hard to find good stuff for teenagers. All the best, Alison

Hi Alison,

I am a fellow SLP and literacy specialist. I love this post and your new visuals for a PA scope and sequence. There seems to be a lot of buzz at the moment around doing oral PA vs PA with graphemes. It is on my list to really delve into the research on this. My understanding of orthographic mapping, Ehri’s work, and more recently, David Kilpatrick’s work, is that proficient oral PA skills are necessary to map and store words efficiently and effectively. Children will typically learn how to decode and encode by working on PA skills in the context of graphemes alongside systematic phonics instruction. However, if oral PA skills are not accurate and automatic then these children tend to be slow and laborious readers due to the impact oral PA proficiency has on adequate mapping and storage. If we just train PA skills in the context of graphemes, the graphemes almost work as scaffolding supports and some students won’t truly acquire automatic PA skills (which by definition is an oral skill so there shouldn’t really be a need for the visual support of letters to truly acquire the skill). Part of me wonders if the research has been misinterpreted. I know some programs or approaches describe PA skills as a precursor to phonics and suggest working on PA skills only before doing any phonics (which of course is not the right approach). Is it possible that in response to this ill-advised approach of treating PA skills as a prerequisite to teaching phonics, researchers have suggested doing PA and phonics together but by together they mean simultaneously?? In my work, I train oral PA skills with the goal of automaticity without visual supports while simultaneously working on phonics, decoding and encoding skills ( I am Sounds-Write trained and absolutely love their program and use it as the foundation for my phonics instruction). I guess the question is this: Although oral PA skills may not be necessary to become proficient in decoding/encoding skills, are they necessary for adequate orthographic mapping? And without it, will some children continue to be slow and laborious readers? Would love to hear your thoughts on this.

Hi Aiofe, I have been a bit bewildered by this myself for quite a while, as on the one hand David K says all effective programs have three components 1) phonemic awareness and proficiency, 2) phonics and 3) lots of reading connected text. However, if you do your phonemic awareness work using letters, isn’t that phonics? It will be great when the PAST Test is normed and the usual performance of mainstream kids can be considered as part of this problem-solving, both kids from balanced literacy classrooms and kids from Sounds Write, Phonographix and other systematic phonics classrooms. The CTOPP is helpful but not timed, and timing tells you whether a skill is laborious or automatic. Given that Phonographix has good evidence and contains no oral-only phonemic awareness work, but works very much speech-to-print, I think oral-only work is optional, as long as the phonics activities you do force kids to think about and say sounds, not try to map directly from print to meaning. Word sequences and lots of spelling work are how I tackle this. With older kids who are really focussed on letters and not sounds I do like to take the letters completely away to force them to think about sounds, but I find that lots of them are visualising letters (if you ask them to change the /f/ in ‘cough’ to /t/ they will say something like ‘court’ or ‘cout’) or surreptitiously writing the words down off-camera to figure it out, sounds are VERY hard for some kids to conceptualise. And given the amount of orthographic interference good readers/spellers experience when doing phonemic awareness tasks (I had a mum today telling her kid there are four phonemes in catch – c, a, t, ch) it’s not surprising I guess. They have a reciprocal relationship, and develop as such. Hope that makes sense and sorry it’s not a complete and neat answer, but I’m pretty sure new research will help us figure this stuff out soon. Alison

I have been wondering about this too, but you articulated it so well! When they say do PA and phonics together, it is literally at the same time, or is it in conjunction? Or do you do PA for 5 min, then phonics for 5 min, and so on? Or do you do one word with oral PA, then the same word with graphemes?

I’ve also wondered about the PA guidance for children with dyslexia. The NRP mostly left them out of their analyses, so I don’t know if we know how best to provide instruction to support phonemic awareness for them.

We use the program Sounds-Write which starts with the spoken word, helps kids segment it and map graphemes onto phonemes, so it’s working from speech to print, not starting with letters and trying to work back to speech. That’s my idea of integrating PA and phonics. I think kids with dyslexia need the same type of intervention but more intensively, and it should start as soon as there’s a red flag about them. Ideally school entry screening should pick up kids with poor PA, low phonological memory and RAN who aren’t recognising any letters, plus any kids with a family history of dyslexia and anyone with delayed articulation, and put them straight into Tier 2 groups for a bit of extra attention and formative assessment. This sort of early intervention would save a whole lot of struggle and pain further down the track.

Yes, yes, yes! Thank you Alison for this informative breakdown.

Yay, Jocelyn Seamer likes my blog post, that means a lot! Thankyou.

A very informative and useful article. I love the diagram you have devised. Thankyou.

Thank YOU for the lovely feedback! Alison

I’m discovering this with my 12 year old severely Dyslexic daughter.

Great article.

Thank you!

But, doesn’t understanding syllables help with spelling understanding?

Table , tablet?

Ta / ble open (open Syllable / cle syllable

Tab / let (closed syllable / closed syllable

great / grate

Why is the ‘a’ long in table and short in tablet? ‘A’ says its name in an open syllable. the code is ‘a’. To spell the long ‘a’ sound in ‘great’ and ‘grate’ we need to use different codes.

I feel like understanding syllables help with codes too?

Hi Kylie, when you get to multisyllable words, yes, kids need to blend/segment one syllable at a time and understand that there’s a syllable for each vowel spelling. By then, their phonemic awareness should be fairly well-established from working at the single-syllable level. I don’t find the rules about open and closed vowels helpful to my learners because they’re too wordy and metalinguistic, I prefer to give kids lots of examples, since we know that understanding our spelling system is really a big data collection/statistical learning activity that proceeds largely subconsciously, not an orderly, rule-based process. We need to give kids a manageable amount of data to learn from at a time, and that varies across kids, some can cope with more patterns at once than others. It’s helpful once kids have learnt about /o/ as in ‘got’ and /oe/ as in ‘most’ to get them to read ‘I put up a poster’ and ‘I’m on the dishes roster’ and try both /o/ and /oe/ for the letter O, and see what words they get. This is an important step in helping kids to be able to teach themselves new vocabulary by reading, and they need to have enough orthographic knowledge and cognitive flexibility/set for variability to try the plausible sounds and see which delivers them a word that they know which fits the context. I like to circle syllables in words rather than dividing them up with lines or gaps, because lines look too much like lower case letter L, and gaps mean rewriting the word, you can’t just add to it. Syllable circles can be added and overlap. For example if you add a vowel suffix to ‘play’, the letter y is part of ‘play’ obviously, but it’s also pronounced as the initial consonant of the next syllable because we separate vowels with consonants when we speak. So I would have the letter ‘y’ in the overlap between both syllable circles. Much more accurate and kid-friendly than breaking words up with gaps or lines based on jargony rules that lots of adults don’t really understand until they see examples! Hope that makes sense, Alison

Thank you so much for the blog and the answer to the above question. This was such a good explanation and recommendation (circling the syllables). I’ve hated the gaps! Please keep writing, your blogs help my tutor lessons become more effective week by week. Love the ‘Phonemic Continuum’ diagram.

This is so helpful to me. I really struggled to teach syllable rules to my students last year and started questioning how helpful all of the syllable rules were. I really like the idea of your approach–seems much more practical.

Hi Alison, I found this post after searching ‘teaching syllable division Alison Spelfabet’. You are my new Google search! Haha! There is so much about teaching syllable division out there but I didn’t know what it was really until the SOR. I haven’t done it with my grade 1’s but wondered if I should. Many get mixed up with what vowels and consonants are. I do like the simple, if it doesn’t make sense, try the other sound/vowel name, etc. My daughter’s speechie used to tell her during her sessions to work on her spelling, “vowels end claps” but she was in year 7 and it didn’t seem to cognitively overload her. I would love it if you could write a post just about this! With reading, does syllable division just come naturally as children read decodable texts? In my experience, initially, they pause and seem unsure but my students seem to get it. Thanks, Little Learners readers! I suppose it is different when approaching spelling. When teaching spelling, should we teach about syllable division? Or open vowel words such as: he, me, no, hi. I do get some children spelling mey (me) gow (go) gowing (going) but to me, this is also indicating that they are really trying to listen to the sounds in words.

Thanks for the nice feedback, this is perzackly what I am trying to work out myself, as there isn’t a lot of really obviously evidence-based information out there about teaching syllable division. Am working on it! I think teaching about prefixes, and suffixes goes a long way towards helping kids manage syllables, but syllable stress is an issue and I don’t quite have my head around that yet. Have to be able to say something sensible this month, though, as i have a conference presentation due about it on 1 April, and I will write a blog about it too. Alison

Fantastic blog post! Thank you

Hi Alison

Thanks for sharing this information. After reading your post I am now questioning the approach we have taken with some students this year and was wondering if you could let me know your thoughts?

We used Ros Neilson’s FELA with our Foundation students for the first time this year. We noticed that students who had difficulty blending/segmenting sounds (CVC) also struggled with the syllable isolation task of the FELA, even if those same students knew all their letter sounds and could count syllables in words. For these particular students, we didn’t focus on teaching rhyme or counting syllables, but we did focus on syllable isolation activities (we also focused heavily on blending and segmenting phonemes, like we did for all students). I suppose our theory was that it may help address their phonological awareness problems, which in turn may help them better blend/segment.

After reading your article (bearing in mind I haven’t yet read the journal article or listened to the podcast you link to), do you think it is a waste of time trying to teach these students to isolate syllables? Do we just simply focus on phoneme blending/segmenting/deletion/manipulation and then over time the phonological awareness problems we picked up in the FELA will resolve themselves?

I think when we are teaching beginners about sounds and letters, we don’t do it in polysyllabic words, so we don’t need to start there. We focus on VC and CVC words, then CVCC and CCVCs. Some kids get quite confused when they’re asked to work with more than one phonological unit/grain size at a time. I’ve seen kids taught to clap syllables who then confuse them with phonemes (and will try to clap things like ‘ca’, ‘aaa’, ‘t’) and kids taught to discern onset and rhyme who then tell you there are two syllables in the word ‘stop’ – ‘st’ and ‘op’. So I like to stick to the one thing that we know matters most from all the phonological awareness research, and that makes most sense in terms of the phonics teaching sequence I use, and that’s focussing at the phoneme level. Yes, when kids get to polysyllabic words they need to know to look for the vowels/vowel groups and break words up into syllables around them, and when spelling to write a syllable at a time. But you can introduce those ideas by building compound words and suffixes, and then move on to other polysyllabic words, and I find that most kids don’t miss a beat. I work with a lot of kids with oral language difficulties and intellectual disabilities, so I try to avoid teaching them linguistics jargon they probably won’t need much in later life, and when we get to two-syllable words I just say ‘this word has two mouthfuls, say them one at a time’ and circle each syllable, if necessary overlapping the circles e.g. for ‘cannot’ it can be divided ‘can-not’ on morpheme lines or ‘cann-ot’ on phoneme lines, so I have a bet each way and put the extra n in the overlap between the two circles, since the doubled consonant indicates/preserves the preceding vowel’s pronunciation. The bottom line for me is that phonological sensitivity isn’t known to glue written words in memory, but phonemic awareness and proficiency is, so that’s the main game. Hope that’s helpful, all the best, Alison

Thank you for the excellent contribution and explanation of your rationale. This is so helpful in my thinking and planning around this.

Thanks Allison

As a prep teacher this is really helpful.

I’m wondering if this means we expect students to start school with that rhyme / syllable knowledge ?

Which is something I have not found to be the case.

I think some kids will always start school with rhyme and syllable knowledge and some won’t. The ones who have it will probably find phonemic awareness easier. After all, rhyming is really changing a word’s onset, and a lot of CVC words have single-phoneme onsets, so for them, rhyming is really the same thing as manipulating the initial consonant. However, there’s no good evidence that focussing on syllables and rhyme helps kids discern phonemes, and there’s a bit of evidence that working with too many different chunk sizes can be confusing. I find that kids with very severe phonemic awareness difficulties can develop their skills in their area very quickly via an intensive synthetic/linguistic phonics approach, with lots of word-building and changing and lots of spelling while saying sounds aloud, plus decodable books to reinforce and embed the phoneme-grapheme correspondences.

Thanks that makes a lot of sense.

We have been teaching syllables recently and I am finding that the kids who as you say find PA easier, catch on straight away.

Whereas it is a fairly foreign concept to those who struggle with their sounds etc.

A great reminder to stick with the basics and make sure they are mastered first.

Thankyou

I have not a rhyme production in hearing range with my little Prep or Year 1 kids, though some can identify 2 words out of 3 words that rhyme. They also know the graphemes for CVC words e.g. when asked, “what is the middle sound in cat?” = “A” (letter name), but not able to isolate the sound itself. I am in a quandary as to what to prioritise as goals for “emergency PA intervention” at this late stage of the term, nay, the year should we be able to return to f2f for at tier 2.

Hi A, I’m not sure what you mean by “I have not a rhyme production in hearing range with my little Prep or Year 1 kids”, sorry. Would they be able to do a workbook that targets PA and segmenting, like this free one? http://www.spelfabet.com.au/materials/free-early-phonemic-awareness-phonics-and-handwriting-workbook. Do you have decodable texts you can send them? e.g. the SA SPELD phonic books, or the Little Learners Love Literacy apps are all currently free. Feel free to ring me to discuss if need be, the office number is 8528 0138.

I love it and can’t see how it can be improved. Will you make it available as a download? I’d love to print it, blow it up and place in staffroom- with your permission.

Thank you for this- wonderful post and wonderful continuum!! I have one quick question- in your draft continuum, was there a reason why you included VC but not CV when listing words with 2 sounds? And you’ve listed VCC but not CCV. Do you think, for two sound words, VC is easier than CV and for three sound words, CCV is easier than VCC or vice versa? Or do you think they are similar and could list VC/CV and CCV/VCC? Just curious and would love your thoughts on this!

We don’t have ‘short’ or checked vowels (/a/ as in cat, /e/ as in bed, /i/ as in win, /o/ as in hot, /u/ as in bus) at the end of words in English, so there aren’t any CV or CCV syllables with these basic spellings. I do show kids ‘hen’ and then take away the ‘n’ and say ‘that’s “he”, we say /ee/ for this letter (e) when it’s at the end of a word”, and do the same for him/hi, not/no etc fairly early on, but right at the beginning when trying to consolidate the link between the vowel letters and the ‘short’ vowel sounds, I don’t like to introduce other vowel sounds. I can imagine a phonics teaching sequence where you might do that, but it’s not the one most people use, the initial code in most sequences sticks to the five most basic vowel sounds (or six if you count the vowel in ‘put’).

I agree with much of this post, but I am not yet convinced about the need to teach phoneme deletion and replacement. Despite what some out there have claimed, there is no evidence that skills more “advanced” than good phoneme segmenting and blending are needed for reading and spelling proficiency. Also consider that learning to read has reciprocal effects on more sophisticated PA.

Hi Nathan, Dr David Kilpatrick is the author of a book which reviews the reading research called Assessing, Preventing and Overcoming Reading Difficulties which says that basic phonemic awareness – blending and segmenting – is sufficient to establish decoding, but that words are only orthographically mapped as units into long-term memory for instant recognition when children automatise these skills and can do them subconsciously, and that’s what phoneme manipulation and proficiency tasks test and require – the ability to take a word apart at lightning speed, change it in some way (take a sound out, swap a different one in) and put it back together, and then say the new word, all within a couple of seconds. I’d encourage you to read the book, and to try this out with proficient and yet-to-be-proficient readers. There are a bunch of kids out there who can decode basic print but aren’t efficiently mapping words into long-term memory for instant recognition, because they aren’t phonemically proficient, so they always read slowly with poor comprehension because they are slogging through mud decoding everything instead of mapping words into long-term memory so that they can recognise them instantly and effortlessly. See also the work of Linnea Ehri on orthographic mapping.

Thanks so much, Alison! I think the age that children start school may vary around Australia. In Tasmania our first school year is children aged 4 (some who have only just turned 4), who turn 5 during their first school year. I just wanted to double check that is the age that is suitable for starting phonemic segmenting and blending? Thanks, Wendy

Hi Wendy, my goodness, I hadn’t realised that kids in Tasmania start school at age 4. Lots of them will still be learning how to say quite a few of the consonant sounds, see https://cdn.csu.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/3119104/Treehouse-A4.pdf, which is a bit of an issue, a recipe for mixing up f/v and th for sure. You’re in the same situation as the UK, their kids start school when they are TINY, but I think they have a year of play and social skills type curriculum before they start on teaching them to read and write, that’s why the Phase 1 work in Letters and Sounds isn’t really teaching kids about letters or phonemes yet, it’s just working on phonological sensitivity and knowing which way to hold a book and turn the pages and so on. There are lots of kids who can learn to segment and blend at age 4, so you could do it, and given Tassie’s literacy data maybe it’s a good idea to make an early start, but it does seem a bit sad to me that four year olds are doing that instead of lots of pretend play and socialisation and oral language activities, as well as lots of physical activity, it’s so hard for four-year-olds to sit still for very long. Also it will be harder for the special needs kids, I think early screening would have to be a top priority to pick them up early and provide them with a good Tier 2. If I was running the education system, I’d just have kids aged six and under doing pretend play, socialisation, physical activities, and learning both their own oral language and at least one foreign language, and start teaching them to read and spell after they’re six. It’s ludicrous that we mostly wait till the critical oral-language learning period is over before introducing foreign languages, and expect really tiny kids to start learning to read and spell when they can’t even say all the speech sounds yet. But the people running the education system don’t seem to understand speech and language development, sigh. All the best, Alison

Thanks Alison, I really appreciate the detail in your responses – I’ve learned a lot by reading your replies to all the comments and questions about your blog

Oh…and as an OT I’d also like to underscore the importance of the “written word glue”. Where there is a limited amount of OT/SP and neuropsych research intersecting with educational outcomes, this is a compelling point. Handwriting proficiency, in an era of increasing use of keyboards and touch screens, is revealing itself to be positively correlated with desirable early literacy measures, and in some cases also with cognitive fn.

Oh My Goodness, you’re an OT as well as a speech pathologist? If you get sick of your current job, and you’re not miles away from North Fitzroy, give me a call!

Brilliant post, Alison! I love your draft replacement continuum. So helpful.

Thanks for the lovely feedback! Alison

I love this, Alison! thank you, once again, for thinking so deeply and clearly about one more specific area of learning and skill building regarding literacy. Thank you for all your work. I currently have some new grad SPs and AHAs who are completing their M.SP and your blog posts are a frequent basis for our clinical discussions. This particular post really struck a cord with one of our team and they re-thought their approach with one older student as a result, with great outcomes for the student. Thank you for your wonderful work. We also tend to work with students with significant additional needs and this thinking really helps us optimise every minute of our sessions.

You’re very kind, thanks for the lovely feedback, glad you’ve found my site helpful. Hope things are going very well and stay in touch. Alison