The nature of reading development and difficulties

12 Replies

Last day of the school holidays. Time to summarise David Kilpatrick’s third excellent seminar, “The Nature of Reading Development and Reading Difficulties”, presented at the 2017 Reading in the Rockies conference.

Here it is on Youtube, if you just want to cut to the chase:

Numbers in brackets refer to the time on the video clock, to help you find sections of particular interest.

(2:14) Tens of millions of dollars are spent on reading research, and the findings go into journals, never to be heard of again, unless you’re a reading researcher.

Working as both a school psychologist and a university lecturer gave Dr Kilpatrick access to these journals, and made him think about their practical application to kids sitting across the table from him in schools.

We need a sound theory based on how typical kids learn

Two leading UK dyslexia experts, Margaret Snowling and Charles Hulme, pointed out in 2011 that, “Any well-founded educational intervention must be based on a sound theory of the causes of a particular form of learning difficulty, which in turn must be based on an understanding of how a given skill is learned by typically developing children”

The field of reading research is huge. About 700 scientifically-oriented journal articles appear in English each year. Nobody can stay on top of all of it, so people become experts in niche areas. Experts in pure word learning research tend not to talk much to experts in word reading intervention, and vice versa.

Being scientists, they seek the truth. This requires humility, because you can only apply critical thinking skills if you’re able to say, “Hey, I might be wrong, I need to learn”. Critical thinking skills are about finding the truth, unlike political thinking skills, which are about defending a particular version of the truth.

(10:05) Are there fewer dyslexics in languages with transparent orthographies?

It’s a myth that there are more dyslexics in English-speaking countries than in countries that speak languages with more straightforward relationships between sounds and letters, like Turkish or Swahili. There are the same number of dyslexics everywhere, but the symptoms are different. English-speaking dyslexics tend to have difficulties with both accuracy and speed. Dyslexics using languages with less complex spelling systems eventually read accurately, and just have problems with speed.

In discussions of dyslexia we tend to focus on getting kids to sound out words they don’t know. We don’t focus enough on how we can get children to remember the words they read.

(14.40) Key terms

- Auditory v/s phonological: Everything we hear is auditory. “Phonological” relates to a subset of this, anything related to the sounds of spoken language. Kids with reading problems but normal hearing don’t have generic auditory processing problems. Their problems are phonological – interacting with the sub-structure of spoken language.

- Phonological v/s phonemic: Phonemes are our abstract ideas of the individual sounds in speech. They only exist by comparison. If we change a sound in a word (e.g. changing /d/ to /t/ in “had” v/s “hat”) and hear it as a different word, the different sounds are phonemes. Phonemes only matter if your writing system is based on writing phonemes. Phonological awareness includes phonemic awareness, and other speech sound-related awareness like rhyming, alliteration and syllables.

- Orthography and orthographic: Orthography is just a fancy way to say “correct writing” (from Greek “orthos” = straight or right, and “graph” meaning represent). “Brane” is not orthographically correct, and the difference between “pair” and “pear” is orthographic, not phonological.

- Phonological awareness v/s phonics: A study in the Journal of Learning Disabilities in 2009 asked teachers of reading to explain the difference between phonological awareness and phonics, and 80% of them couldn’t do it. If you see the letters, that’s phonics. Phonological awareness is when you’re dealing with the sounds.

- Sight word and sight vocabulary (orthographic lexicon): The term “sight word” is used four different ways in education, but to reading researchers a sight word is any word that is familiar to you and jumps out at you. It could be regularly or irregularly-spelt. It might be high-frequency and learnt long ago, or a technical term you recently learnt. It’s any familiar word that you don’t have to put effort into identifying. So a sight vocabulary is all the words like that. Typical adults have thirty to sixty thousand words in our sight vocabularies, words they can immediately read, even if they only see them for a 20th of a second. No context, no sounding it out, that’s sight vocabulary. Children with dyslexia have very limited sight vocabularies, so teaching them needs to focus on how sight word development works.

(20:49) A researcher’s definition of dyslexia

There are multiple definitions of dyslexia. Here’s a researcher definition that emerges from reading hundreds of relevant studies:

Word level reading difficulty despite adequate opportunity and effort.

The only visual aspect of dyslexia is the input. After that, words are remembered based on orthographic memory, phonological memory and semantic memory, not visual memory (except in cases of blindness, deafness and very severe intellectual disability).

Most kids with disabilities can learn to read words

Kids with even mild or moderate intellectual disabilities can learn to read words quite competently. They might even become hyperlexic, that is, able to read above and beyond what they can understand.

Many students with mild intellectual disability – maybe IQs of 65 – have verbal reasoning at about a fifth or sixth grade level, but finish high school with reading comprehension only at a second or third grade level. The reason is that they have word level reading at around a first grade level, which drags their reading comprehension down.

As researcher Joe Torgeson said, teaching should ensure every child’s reading comprehension is at the level of their language comprehension. Adults with mild intellectual disabilities will cope much better if they have a fifth or sixth grade reading level, not a third grade level.

Kids with disabilities struggle with word reading for the same reasons as everyone else, provided there’s been adequate opportunity and effort. If a child spends their whole time swearing at the teacher and throwing chairs, that of course interferes with learning, but often they don’t get identified unless they swear and throw chairs.

We should never say that the reason a child is struggling with word level reading is because they have a disability. We need instead to talk about the skills that go into word level reading.

(25.35) The Phonological Core Deficit of dyslexia

The Phonological Core Deficit used to be called the most common cause of dyslexia. In recent years there’s been a shift, and it’s now considered the universal cause of dyslexia. It is characterised by problems in one or more of:

- Phonemic awareness/analysis

- Phonemic blending/synthesis

- Rapid automatised naming

- Phonological working memory

- Nonsense word reading, letter-sound acquisition.

Kids usually have problems in more than one area, and sometimes in all five.

We have been looking for other causes of dyslexia for decades, to no avail. We have a phonemic-based writing system. If you struggle with phonemes, you’re going to struggle with the writing system. The letter system is just simple data entry.

Our intuition is that reading problems are to do with vision, but they’re not. In 2009 the American Academy of Paediatrics pulled together optometry and opthamology organisations to put together a statement saying dyslexia is not a visual problem.

(32.45) Common assumptions about reading

Some common assumptions appear to contribute to a large proportion of reading difficulties. We all have a theory of reading, whether it’s explicit or implicit, which will be reflected in the interventions we use.

Most approaches, including both phonics and whole language/three-cueing, focus on identifying new words. They don’t directly address the issue of how kids remember words. We need to address this.

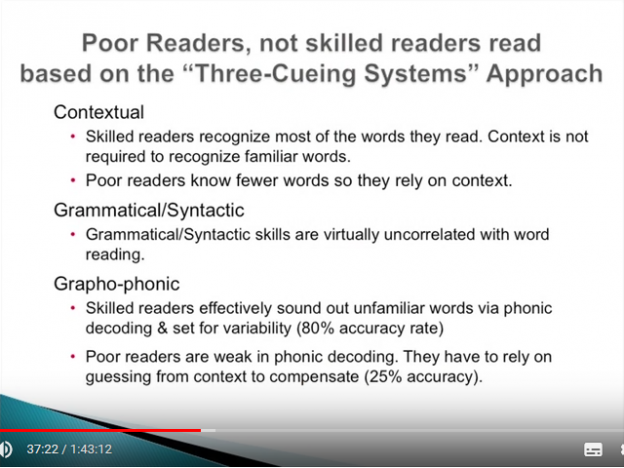

The three-cueing system has been a major force in reading education since the 1980s. It keeps changing its name, first it was called Whole Language, then Literacy-Based, then Balanced Instruction, sometimes it’s now called MSV, and it’s continuously affirmed as valid despite extensive evidence to the contrary. There is no evidence that it helps weaker readers catch up, and extensive evidence that it does not.

It was based on ideas in the 1960s that were as good as any other ideas at the time, because we didn’t then have a better theory of how we remember words. Linnea Ehri figured this out in the late 1970s, and her theory is now pretty much accepted by researchers around the world.

Humility says, “my idea might be wrong and I might have to change my idea”, but that hasn’t been the approach taken by advocates of the three-cueing approach. The concepts have been the same since the 1960s, and have been repeated so often that they sound truthy.

(37:22) How skilled readers read

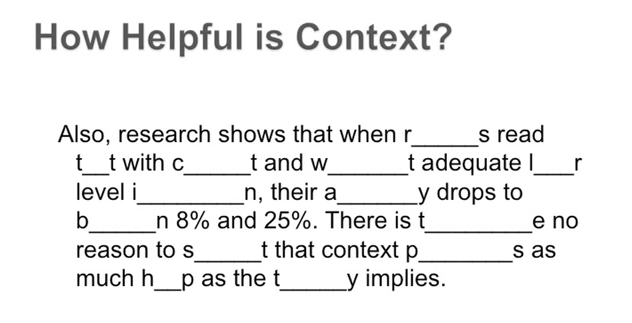

As it turns out, skilled readers do not use context to read familiar words. They read unfamiliar words using phonic decoding, set for variability (explained later) and perhaps some context. It’s only poor readers who have to rely heavily on context.

Grammar and syntax are hardly relevant to word level reading, they don’t even correlate with it.

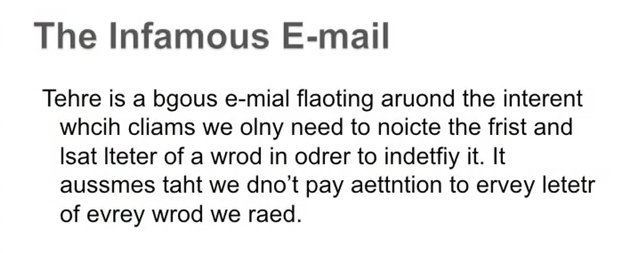

A skilled reader can rapidly read a list of words with no context. The only words skilled readers need context to identify are homographs – words with two pronunciations, like “dove” (into the pool) and “dove” (the bird), which are less than half of 1% of words.

In garden path experiments, people have been given paragraphs that lead them to expect a certain big word right at the end, except they put a different word that is only one letter different. 95% of skilled readers still read the word correctly, which they wouldn’t do if they were relying on context.

Context, grammar and syntax are all essential for comprehension. It is only possible to say what the words “rose”, “match” and “ring” mean when they’re in context. But you can read any of those words instantly without context.

About half the high-frequency Dolch words are phonically irregular, but other words are much more regularly-spelt.

Set for variability

Set for variability is the ability to correctly identify a mispronounced word. We use it all the time when we talk to people with different accents and they pronounce words a bit differently.

Anyone who’s taught reading is familiar with the kid who says, “isss-land…isssss-land..island!”. They are able to do this because of set for variability, and it’s easier to do if you have a large vocabulary.

Guessing from context has about a 25% accuracy rate, whereas using phonic decoding and set for variability has about an 80% accuracy rate. Guessing from context is very inefficient, and it’s not how skilled readers read.

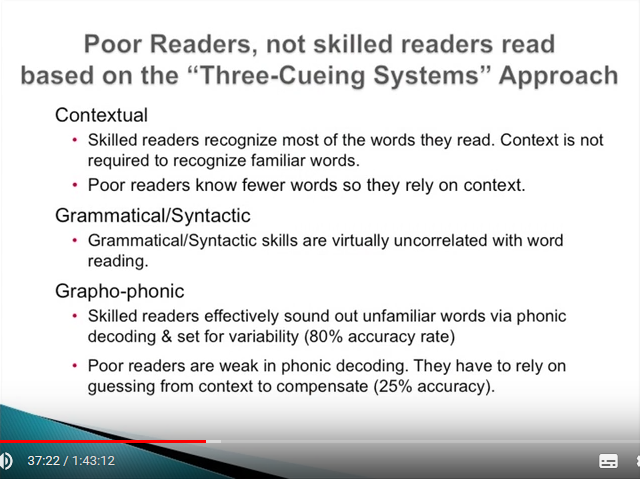

The Infamous email

The information in the email is false, but the email is a demonstration of contextual facilitation, which is a type of top-down processing. However, it tells us nothing about normal word recognition. If you’ve ever received an email like this, it’s a hoax. Cambridge University even has a web page debunking it.

The difference between identification and recognition

If you have to identify someone you’ve never met, but you have a good description and you know where to find them, you can probably do it, even though you don’t recognise them. Recognition assumes past knowledge and memory. So if your best friend walks in, that’s recognition.

Word recognition has to do with words we already know, the sight vocabulary. Identification is a broader term that includes words we recognise, but also ones we sound out or guess from context.

We have thousands of words in our sight vocabularies, that we can’t help ourselves from reading. But if the writing becomes harder to read, then you have to use top-down processing, using context. Try this:

(49:45) Sight words are not recognised via visual memory

When we recognise and name both a real chair and the written word “chair”, it subjectively feels like the same process. Both involve visual input and verbal output.

However, input and storage are not the same thing. The input for written words is visual, but the storage is orthographic, phonological and semantic.

James Cattell published an article in 1886 about an experiment in which he flashed words and pictures on a screen, and measured how quickly people could name/read them. He found that people consistently named the printed words (e.g. the word “chair”) faster than the pictures (e.g. a picture of a chair). So in 1886 we had our first bit of evidence that there is a difference between visual memory for objects and what we now call orthographic memory.

In the 1970s lots of experiments found that dyslexics have the same visual skills as everyone else, but that still didn’t stamp out the idea that dyslexia is something to do with visual memory.

Researchers initially found that reading in a mixture of upper and lower case was slower than reading in a consistent case. They later found that after a little practice reading MiXeD CaSe, subjects were no slower.

In the first tenth of a second, the look of a word becomes irrelevant

Even if you teach kids words in lower case, and then present them in upper case, they read them without difficulty, because we have an abstract representation of each letter. In the first tenth of a second when we look at a word, its appearance is stripped out, and only the sequence of letters is processed in the left fusiform gyrus, within three-tenths of a second.

If a word is identified, information then goes to our speech centres, so we can pronounce or think the word. Even during silent reading, our speech centres are quite active.

Marilyn Jager Adams did an experiment where she flashed words in UPPER, lower and MiXeD case on a screen, and asked students to read them. After the experiment some of the students insisted that all the words had been in lower case.

We all sometimes have trouble finding the names of people we know, and even names of objects. We never do that with familiar words, because recognising letters is very basic. In one experiment they taught kids (with and without dyslexia) a made-up alphabet, and found very little variability in their visual skills, but a great deal of variability in their phonological skills.

Most Deaf students struggle with word-level reading, and many graduate from high school with about third grade level reading skills. If reading were based on visual memory, they wouldn’t.

Since 2000 there have been many neuro-imaging studies which show that when we see a chair, a different area of the brain lights up from when we see the word “chair”. Visual memory and orthographic memory involve different areas of the brain.

We have to get past the intuitive notion that reading is based on visual skills. It’s not. Once the letter string has been received, vision has done its work.

(1:05) Concerns about the efficacy of phonics

You can’t become a proficient reader without phonics. However, we need to question the efficiency of traditional phonics teaching methods. Hammers have been around for ages and they still work, but these days roofing companies use nail guns, because they’re more efficient. Decades of relevant research was not available when teaching methods like Orton-Gillingham were devised.

For two-thirds of kids, the benefits of phonics teaching wash out over time. Even if you don’t teach them phonics, they learn phonic skills eventually. It’s simply not possible to read an alphabet-based language without phonic skills.

The bottom third of kids cannot figure phonics out themselves. They have to be taught explicitly and systematically. The beneficial effect of this teaching is maintained over time.

However, many kids taught phonics still don’t catch up, and don’t read fluently. There’s also a small proportion of kids who don’t seem to benefit from phonics.

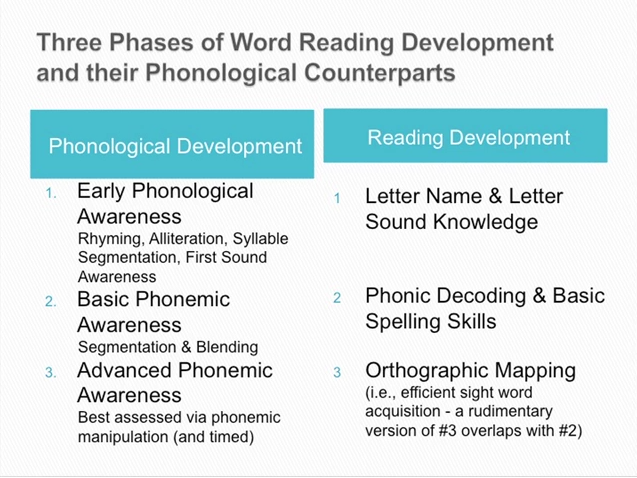

Traditional phonics instruction has no built-in mechanism that allows kids to build a large sight vocabulary. The Self-Teaching Hypothesis of David Share offers this mechanism, but requires learners to have adequate phonological and phonemic proficiency (not just awareness).

The problem is phonological, not visual

Children with phonological core deficits respond differently to traditional phonics:

- Kids with mild phonological core deficits (the majority) do well in systematic phonics programs. Phonics is enough to stimulate their phonemic awareness, develop phonemic proficiency and start remembering the words they read. So they catch up. They’re the success stories you read about on phonics program websites.

- Kids with moderate phonological-core deficits learn phonics pretty well, and eventually pass tests of nonsense word reading, which are our best test of phonic skills. However, their real word reading and fluency remain poor, because their phonological proficiency remains low, so they can’t remember the words/develop their sight vocabulary.

- Kids with severe phonological core deficits don’t even seem to benefit much from phonics. These are the kids who can’t even do phonological awareness test items intended for six-year-olds, like “say sailboat, now say it again but don’t say sail”. They can be very intelligent, but without phonological awareness and proficiency, they can’t even decode.

Neither Three-Cueing/Balanced Instruction nor traditional phonics teach phonemic awareness and proficiency explicitly enough for the kids with moderate or severe phonological-core deficits (this is illustrated nicely in a cartoon at 1.12.40).

Crash course in how words are learned

We say we write words, but in fact in alphabetic languages, we write sequences of characters that represent sequences of phonemes in spoken words.

Writing was invented many times – hieroglyphics, cuneiform, Chinese characters etc. Alphabetic writing that encodes the sounds of words was invented once, in about 1700BC by the Phoenicians, in what’s now Syria. All alphabetic writing systems are based on their alphabet.

Poor cognitive access to the phonemes makes reading and writing alphabetic languages very difficult. Phonemic skills are essential both for sounding out and remembering words. Their phonemic nature allows us to remember words as whole units.

(1.16) The Simple View of Reading

The Simple View of Reading (Hoover and Gough, 1990), which has been validated by hundreds of studies, says that reading comprehension is based upon two very broad skills: 1. word-level reading and 2. oral language comprehension.

If either of these skills is weak, reading comprehension will be weak. Educators need to understand these components to offer effective assessment and remediation. Four types of reading difficulty result:

- Dyslexia – can’t read the words well.

- Hyperlexia – can read the words but not understand them. English-language learners often fall into this group because they are able to decode but they don’t yet have the oral vocabulary to know what they all mean.

- Mixed/combined or “Garden Variety Poor Reader” – struggle with both reading the words and understanding them. Their word reading problems are usually the easiest to remediate.

- Compensator – usually very bright (~IQ 105 or higher), with mild phonological issues but good set for variability, so they get more words correct on untimed tests, and can end up with scores in the average range. However, they are not reading efficiently, and this can be identified using a timed test of word reading.

(1:20) Recommended tests

Two strongly recommended tests are the Comprehensive Test Of Phonological Processing-2 (CTOPP) and the TOWRE-2. The TOWRE-2 is great in early primary school (less good with older kids) because kids have 45 seconds to read words, and the compensators can’t compensate their way through it. Sounding out words and using set for variability slows them down, and the clock is ticking.

These are some of our brightest kids, and they could be doing much better, but we don’t notice their poor phonemic awareness and poor fluency because we don’t specifically test them. We might only identify them because their spelling or general writing is poor, or they have behaviour problems. Good Tier 1 work will eliminate most compensators’ problems.

(1:26) The self-teaching hypothesis

We teach ourselves most words we know, by sounding them out. We aren’t consciously making the connection between sounds and letters, but that’s happening, and that’s what allows us to teach ourselves new words.

A typical child only needs 1-4 exposures to a word for it to be added to their sight vocabulary. From second grade on, if children need many more exposures to words, that’s a sign of dyslexia, because they are not mapping the words.

To turn a word into an instantly accessible sight word via orthographic mapping requires:

- Letter-sound proficiency (instant and automatic, with no conscious effort)

- Phonemic proficiency (which goes beyond what’s tested in basic screeners of phonemic awareness)

- The ability to establish a relationship between sounds and letters unconsciously while reading.

About 60-70% of students develop this skill through exposure to literacy activities.

Second graders who are good readers can rapidly do phonemic manipulation tasks like ‘say fly (“fly”), now say it again and change l to r (“fry”)’. This task requires them to segment the word, isolate the target sound, change it and then blend the word back together, all in under a second.

(1.31) When we decode a word, we activate the spoken word, and once we have the spoken word and are able to pull the word apart into sounds, orthographic mapping is like putting suction cups on the sounds and attaching them to the letters. After 1-4 exposures, the connections between the sequence of sound and letters gets unitised and the word becomes a sight word. Dyslexics do this inefficiently, and therefore take a lot longer to remember words.

We don’t just map phonemes, we also map larger word parts like onsets, rimes, prefixes and suffixes, to develop orthographic knowledge. We store sequences as if they are words.

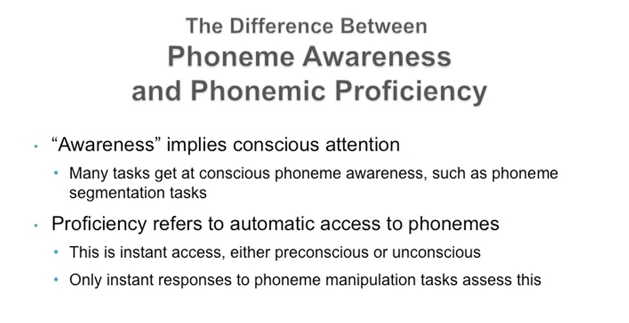

Phoneme awareness is not enough

Some struggling word readers, especially compensators, can change the “l” to “r” in the word “fly”, but they take four seconds. They do it by thinking about the letters and swapping a letter out, then reading it back, because they don’t have automatic, unconscious access to the sounds.

To be successful at orthographic mapping, kids need to be able to automatically and unconsciously segment words into sounds. But you can’t test automatic, unconscious segmentation by giving a child a segmentation task, because the task itself makes them think consciously about segmentation.

Assessments targeting basic skills like rhyming, blending and segmenting are thus only useful for kids in the first couple of years of school. They don’t tell you much about older kids’ skills, they need a phonemic manipulation assessment that requires automatic, unconscious segmentation. This is mostly done via deletion and substitution tasks, which strongly correlate with successful reading in older kids, and all the way up to adulthood.

Common misunderstandings about the role of phoneme skills in reading include that they only relate to consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) words (like ‘hen’, ‘sit’ and ‘cup’), that they’re not involved in sight word acquisition and aren’t worth training after first grade. Some people also still think that phoneme skills are a byproduct of learning to read not causal (only true for the top two-thirds of readers).

This slide appeared in one of the earlier seminars, but please tattoo it into your brain:

We have been focussing all our attention on the right side of this scenario. We now know that there is a causal relationship between phonological and reading development. If you give preschoolers who don’t know any letters phonological awareness training, they learn their letters more easily. Conversely, teaching letters builds phonological awareness in typical kids. Poor early phonological awareness is an indicator of the phonological core deficit.

Humans only need phonemic awareness if they have to read an alphabetic writing system. Years ago, Chinese adults couldn’t do phonemic awareness tasks, because their writing system did not require it. Now they do pinyin using the Roman alphabet, so they do learn them.

Without advanced phonemic awareness instruction, kids with moderate or severe dyslexia will never develop the phonemic proficiency which is the foundation of orthographic mapping.

1. Snowling, M.J. and Hulme, C (2011). Evidence-based interventions for reading and language difficulties: Creating a virtuous circle. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 81, 1-23.

Thanks for providing this great summary, Allison.

Working memory is cited as a bigger indicator of future academic success than IQ. Slow processing speed & poor executive functioning skills are often mentioned as co-occurring morbidities for students with dyslexia. Do you have any information on how teachers can best teach students to remember words?

Can all students with deficits in phonological skills improve with remediation? When there is a deficit in early oral language, what are the best evidence-based methods to help these students? I teach Kindergarten and can already see huge gaps between my students. Any insights would be greatly appreciated. Thank you.

I’ve got the same questions. I’d also love to know what instruction for those kids severe phonological deficit looks like? I’ve watched the video and read your excellent summation, Alosoj, but I still feel like I’m none the solider about how I’d help those students who fall in that severe category.

The instruction for kids with severe phonological deficit looks the same as for everyone else but the steps are very tiny, it never skips a step and often repeats steps. There is a free course on Udemy that shows you what to do for beginners, see http://www.udemy.com/help-your-child-to-read-and-write. I hope it’s helpful and let me know if you want more ideas. I also use my Workbook 1 with a lot of kids with additional needs, have a look at my video here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nZC3Iwp_6IE, this little boy had more than just phonological difficulties, and the last time I had contact with his team he was learning to read and spell pretty well.

Hi Lynette, you’re most welcome, summarising things like this really helps me get my own head around them, so it’s great if others benefit too.

I am yet to find a student with a phonological deficit who can’t improve with remediation, it’s just slower and harder when they have oral language and/or working memory and/or exec functioning and/or processing speed difficulties. When there is a deficit in early oral language at preschool level, the best thing to do is refer them for a speech-language assessment and then follow the recommendations. Some kids have more problems with vocabulary, others with syntax, others with concepts etc so if you know which areas are weakest you can focus on them. Before they start school kids should also be learning about rhyme and alliteration, how to discriminate the first sound in a word, and learning their letters. This sets them up well for school. There’s no effective intervention for working memory difficulties that I know of, it’s maturational, so kids just need smaller amounts of information to think about at a time, and more practice of each skill and concept to make sure it’s gone into long-term memory.

Hi Alison,

thankyou for posting these summaries, I found them inspiring and purchased the Equipped For Reading Success book by David Kilpatric which has been a turning point for me as it answered the question why my gifted son who performs age appropriately on basic phonological screening tests like the Sutherland Phonemic Awareness Test cannot remember even the most basic sight words and is years behind in reading. (He is 8 years old, grade 3, he sounds everything out and makes great guesses giving him a PM level of about 11.) It confirmed for me that his difficulty does have a phonological base and is not some kind of visual memory difficulty and that despite what I have been told, dyslexia does exist and my son most definetly has it! (I had his visual processing skills assesssed by a behavioural optometrist and he scored 5 years above his chronological age on these – so I should have known that). David explains why my son can’t map words. – Thank-you! I’d love to assess him on a C-Top or perhaps the Lindamood assessment and see how he performs with the higher level phonemic manipulation tasks. I suspect he would not do so well. I have just begun the journey of trying to find out how to help my son. I am also interested in becoming a tutor myself and am looking to complete some training and invest in a comprehnsive program I can use with my son. I am an SLP in QLD- working in the disability sector for the past 15 years, I recently completed teacher training and now work in a Kindergarten. The number of programs out there is overwhelming. Would you recommend Sounds-Write or Cracking the ABC code? From what I can see Sounds-Write may be pitched at a younger level for my son?

Hi Karen, thanks for the nice feedback, glad you found my blog helpful. I think Sounds~Write is great and can be used with any age, you just need different books for older kids, I use the Dandelion catch-up readers a lot, Magic Belt hits a home run with a lot of 8-year-olds in my experience. I don’t have Cracking the ABC Code but I think it’s pretty good, you just need to make sure that it includes the advanced PA work that will help your son with mapping, which I think you’re probably doing with Equipped for Reading Success. All the best, Alison

[…] advice flies right in the face of scientific evidence showing that context and syntax are not involved in skilled word-level reading. […]

Hello Alison, Thank you for the summary. This was a fascinating video. I have a 10 year old who still sounds out every word and knows very few sight words despite scoring far above average on intelligence tests. What is puzzling is that she seems to score well on phonological awareness assessments. She breezes through phonological interventions exercises as well. She is a mystery to her resource teacher and tutor who have both have extensive experience and education in this field and who have worked with hundreds of child with dyslexia.

Her CTOPP scores fall in the normal range for all areas with the exception of Rapid Letter Naming. She has had other phonological testing in which is tests in the normal range as well. And then I’m going to go ahead and say it…. Her working memory (LET-II) scores fall in the 1%tile for both Long and Short Term Visual Sequential and a Visual Memory in the 7%tile. If one didn’t know any better one would think this is a visual memory issue, especially since all intervention programs show no improvement in word retrieval. These include extensive OG intervention and LindaMoodBell Seeing Stars and LIPS and several other programs.

What Am I missing?

Have we not tried the correct program?

It has also been suggested that my daughter has Dyseidetic Dyslexia and there is no effective interventions

Thank you!

Wow, Kristin, you ask hard questions. Low visual sequential memory and low RAN but everything else OK. I’m not an expert on visual sequential memory, and only know the basics about RAN, so am not sure what to think. If you like, I can put a summary of your question on the Spell Talk and/or DDOLL email network where lots of experts around the world discuss tricky things like this. Would you be happy for me to do this? Of course not mentioning your name (though you have mentioned your name here so I guess you’re not too worried about that). Alison

Alison that would be amazing and I would be very grateful if you shared! I can even send you the summary pages of the assessment results. Can I send you an email? Thank you so much.

yes, I’ve emailed you directly, lets see if we can ask the brains trust

So many gems in this lecture. Loved learning about “the straw man” theory. Seems to capture so much in my adult disability area. Also the need for humility in researchers to not only seek to prove what they wanted to support, and dare to truly inquire. Gold!