Things tie together when you have a really good theory

36 Replies

There’s some free online learning that I’d recommend to anyone who works with beginning or struggling readers/spellers. You’ll find it on the Colorado Dept of Education website and was recorded at the 2017 Reading in the Rockies conference (thanks to the organisers!).

However, it’s three videos, each more than an hour long. Teachers are time-poor. They understandably aren’t keen to watch long work-related videos unless they know what they’re about, and believe they and their students will benefit.

So I’ve decided to write a blog about each video, summarising what I think are the key points, and recording the time on the video clock each is made, to assist those skimming to find topics of interest. I hope people will then be motivated to go back and watch the whole thing.

The videos’ presenter is Dr David A. Kilpatrick, a US school psychologist turned academic, whose book “Essentials of Assessing, Preventing and Overcoming Reading Difficulties” also explains these concepts (no, I’m not on his marketing team, it’s just a good book, my copy is very dog-eared).

The first video is about preventing word reading difficulties and intervening with those who struggle. Here it is, if you just want to watch it yourself straight-up. My summary is below, numbers in brackets are video clock times, and any oversimplifications or misrepresentations are my own, my apologies. If you see something you think needs fixing, please tell me.

How we remember the words we read: orthographic mapping

In the 1970s and 1980s Linnea Ehri developed her theory of how we remember the words we read, via a process called orthographic mapping, which bonds the sounds in spoken words to their spellings. This theory is constantly cited in the reading research.

In 1994 some researchers including Snowling and Hulme tested out Ehri’s theory in three airtight studies, and found that (as far as anything ever does in science) it stacked up very well. Then in the early 2000s, Torgeson called it our best theory to explain skilled word-level reading.

However, Ehri’s theory hasn’t had much traction in education, or in other areas of the reading research, perhaps due to professional silos and the complexity of the theory.

Orthographic mapping is quite a hard concept to get your head around, and it seems that people have often cited Ehri without really understanding her.

But when you read thousands of research reports through the lens of a really good theory, things start to tie together.

How to reduce reading failure by 75%: understand the research

(5:34) The schools where Kilpatrick was working had been doing Reading Recovery, and not getting great results, but then switched over to intervention consistent with Ehri’s theory, and within five years reduced reading disabilities by 75%.

Once teachers understood the theory, they changed their teaching, and got great results. Our prevention and our intervention has to be based on how reading works.

(8:00) Phonemic awareness and blending matter for how well you can read. Rapid Automatised Naming (RAN) also matters, but even the best researchers in the field aren’t really sure why – whether it’s a separate cause of problems, a consequence of the phonological core deficit, or related in some other way.

(9:50) Phonological memory (the passive, temporary buffer in which we store whatever we just heard for a few seconds) and working memory (our mental workspace) also matter for reading, and both are phonological in nature, but whether problems in these areas are also symptoms of the phonological core deficit, or related in some other way, is also unclear.

Children with limited working memory, who struggle with reading, spelling and also maths, benefit from repetition and multisensory teaching. Limited working memory slows down learning, but does not mean a kid is not smart.

(15:20) What we do know is that visual memory is not how we read. We read based on orthographic memory. We don’t read by guessing from context. When you combine sounding out and set for variability (the ability to determine correct pronunciations from incorrectly pronounced words) you can get a lot of unfamiliar words, you don’t need to guess.

(16:00) Orthographic mapping is how we learn new words, and thus is true of words with both transparent (regular) and opaque (irregular) spellings. Kids who are good readers are good orthographic mappers. Kids who learn to orthographically map can close the gap between themselves and their peers.

Written words are anchored mainly to their sounds, not their meanings

(17:25) Words we’ve heard before are stored in phonological long-term memory, regardless of whether we know their meanings. Once we learn their meanings, we add them to our semantic long-term memory. There are more words that we’ve heard than words that we know.

Second language learners and young children thus have a much larger store of words in their phonological LTM than their semantic LTM. Research by Kate Nation and others has shown that the main anchor point for learning new written words is whether the word is in phonological LTM, not whether it is in semantic LTM.

(23:40) Yes, concrete words are remembered a little more easily than abstract words, so semantics does play a role, but the main way we get written words into long-term memory is by anchoring them in their sounds, not their meanings.

Awareness/knowledge versus proficiency

(25:00) Storing written words in long-term memory requires not just phonemic awareness and letter-sound knowledge but phonemic and letter-sound proficiency.

When you have phonemic proficiency, words pull apart into their component sounds automatically, and link to letters/spellings without any need for conscious effort. These skills have become automatised.

(28:12) This then allows you to teach yourself new words, as per David Share’s self-teaching hypothesis. Even if you don’t know what a word means, if you’ve heard it before and then see it in written form, you can start to match the written form to the spoken form, and in this way teach yourself new words by reading.

Regular and irregular words are mapped the same way

Learning phonics helps with the mapping process, as it makes sense of the words that don’t have transparent relationships between sounds and letters.

(31.50) We used to assume that phonics was good for figuring words out, but that after you’d seen a word a few times, you just started to remember it through visual memory. This is simply not true. We make the connection through mapping, and mapping is easier if you know how the letter patterns work.

(33:00) Irregularly-spelt words are only exceptions if you are using a phonic decoding strategy. Orthographic mapping works from pronunciation to spelling, not the other way around, so once you have a spoken word in your phonological memory, and then you meet it in printed form, it is secured in the same way regularly-spelt words are secured.

Most irregularly-spelt words only have one sound spelt an unusual way, and the rest of the word is spelt pretty normally. In our relatively opaque spelling system, we need to make adjustments all the time, it’s just that some are common adjustments and some less common. The mapping process doesn’t distinguish between regular and irregular words.

Reading practice doesn’t help kids who can’t orthographically map

(38:54) Psychology reports often make three key recommendations: do a lot of reading practice, learn to decode, and learn irregular words as whole units.

However, if you are a child who doesn’t remember words efficiently, reading practice is of very little benefit. First you have to develop phonemic and letter-sound proficiency, so that you can start orthographic mapping, and thus benefit from reading practice.

If you’re a child who DOES remember words, reading practice is essential, and the only thing that will make you a better reader.

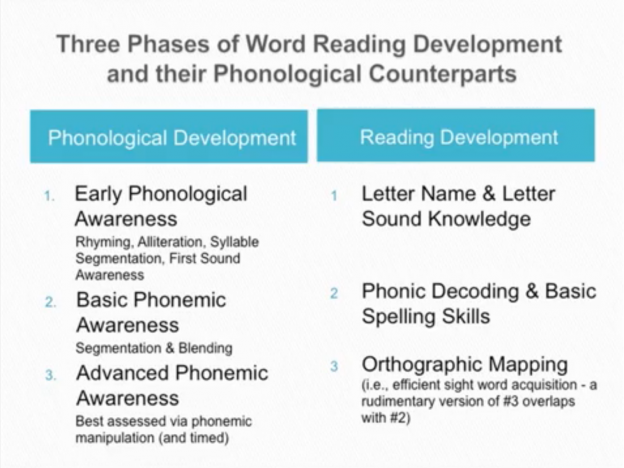

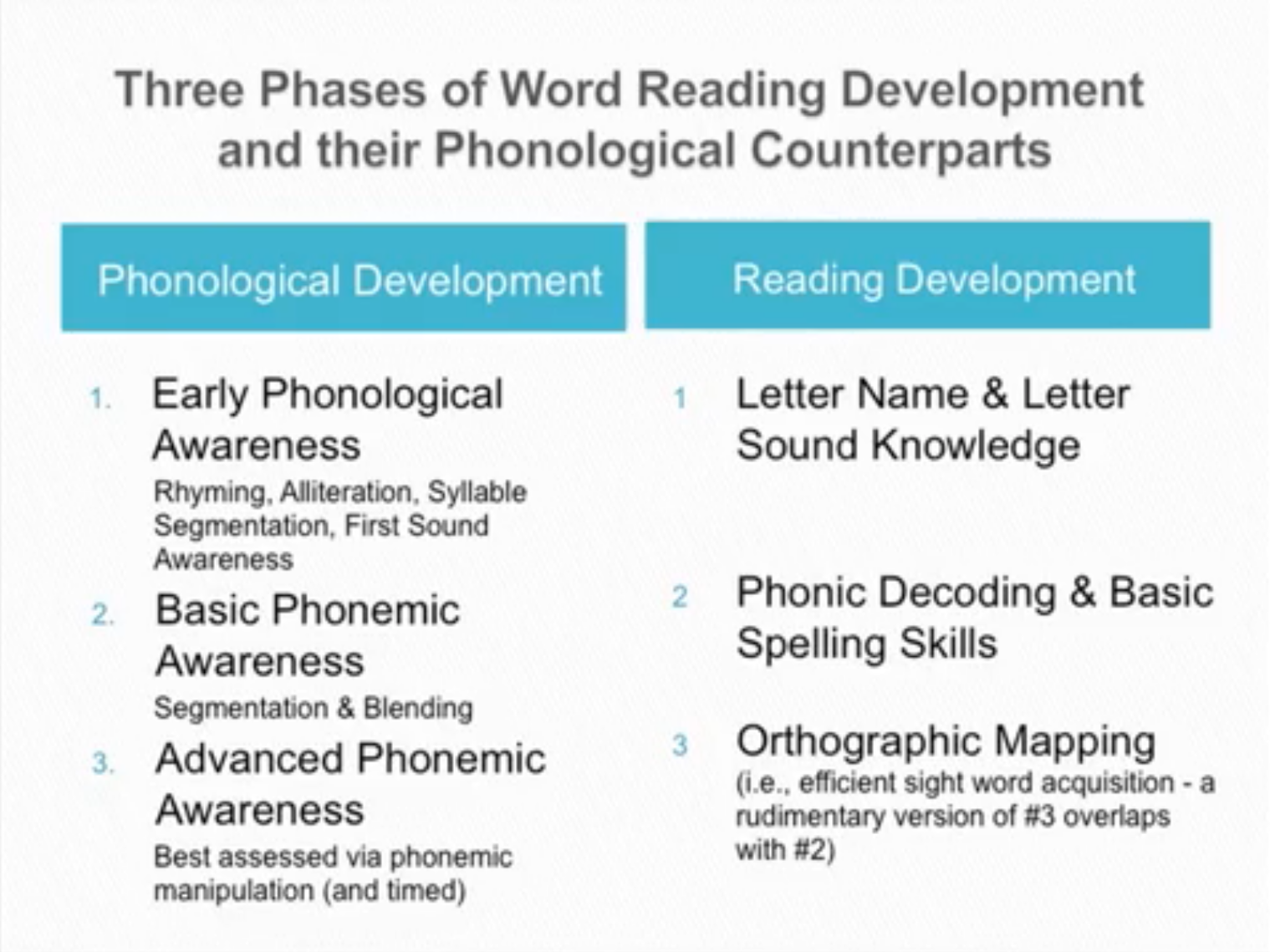

Put this chart on your wall

The things on the left-hand side of this chart are hard to observe, and in typical children happen naturally as part of the process of being taught to read and practising reading and spelling. However, they do not occur naturally in children with the phonological core deficit. The right side skills are the ones that are easier to observe.

If you’re using the CTOPP test to examine skills on the left-hand-side of this chart, the blending test usually tells you nothing after about second grade, as by then most children can blend, it’s the elision test that tells you whether they have the advanced phonemic awareness that will allow them to start orthographic mapping. This skill usually starts in late second or early third grade, and leads to phonemic proficiency.

Prevention of reading problems

(48:50) If we teach all young children phonemic awareness and explicit letter-sound skills, all kids improve their reading performance, on average by about eight standard score points (on standardised tests, where the average is 100 and the average range is 85-115).

The whole group does not retain this gain over time, it drops down to about four standard score points, because typically developing kids develop phonemic proficiency no matter how you teach them.

However, the weaker/at risk kids do gain about 13 standard score points. This increases to about 20 standard score points over time. So there was a well-sustained benefit to the bottom third of children. So it’s very important to teach this way in the first two years of schooling.

(50.30) Why doesn’t everyone teach this way? People say “it’s boring”. Well, yes, if you want to do it in a boring way. It’s a matter of style not content.

If we keep using current early literacy teaching approaches, the bottom third of kids will stay at the bottom. As Mark Seidenberg says, we’re teaching all kids to read like weak readers, by guessing, and only using their linguistic skills as a backup.

(52:30) One interesting experiment used an unfamiliar alphabet to write familiar 3, 4 and 5-letter words, and taught typical kids to read the words via whole word flashcard teaching. They never told them what the letters were. Then they gave them brand new words made up of these letters with the same sound-letter relationships, and found the kids could read them because they had worked out the sound-letter relationships. That’s how alphabetic writing works, and that’s the only way we can read words.

Only between 2% and 5% of children should be struggling

(54:27) Another piece of research took children who were at the 18th percentile and below and divided them into three groups. They were all doing three-cueing systems-based intervention.

One group were taught in classrooms with explicit direct teaching about sounds and letters. Another group had this classroom teaching embedded in word-family activities, which is OK as a starting point/early crutch, but doesn’t make sense if continued. It’s sounds and letters that matter for decoding. A third group had only implicit and incidental teaching about sound-letter relationships.

The kids taught explicitly and directly had standard scores averaging 96 (right in the middle of the average range) compared with 88 and 89 in the other two groups.

44-46% of the kids in the embedded and implicit phonemic awareness and phonics groups made no progress. Only 16% of the kids receiving explicit, direct teaching made no progress, which is 2% of the total population of children not making it to average.

(59:48) American educational journals are now not publishing studies showing that explicit teaching of phonemic awareness and phonics is the best way to teach kids to read, because they think it’s a settled issue.

In 2008, UK researchers Shapiro and Solity published a study that showed that explicit, systematic teaching of phonemic awareness and phonics left only 5% of children struggling, whereas business as usual teaching left 20% of children struggling. So they had a 75% reduction in reading problems based on several minutes a day of phonological awareness instruction and letter-sound instruction.

Planned, small group phonemic awareness and phonics teaching

(1:01:00) The key to successful teaching is the combined teaching of phonemic awareness and teaching of phonics, not just teaching more phonics. Once kids can sound out nonsense words, they have enough phonics. Teaching in both areas must also be systematic, as non-systematic instruction is no better than no instruction. Systematic means, “I have a plan, it’s going to start with easier developmental things and work up to harder things”.

The length of teaching time required is something that varies between studies. One study did seven weeks in kindergarten small groups, four days per week, and this had huge preventative benefits. Others did a whole year. Some groups worked at the pace of the weakest kids, so more able kids were able to do tasks easily, and enjoyed this, but at the end of the year all the kids had the skills they needed, and nobody was left behind.

(1:06:54) The key components that make preventative teaching effective are phonemic awareness, teaching about letter-sound relationships, and reading connected text. However the National Reading Panel’s conclusion that studies using letters to teach phonemic awareness had better results than ones that didn’t use letters is misleading, if you go back and look at the original research.

If you’re teaching with letters, you’re doing phonics. If you’re teaching children to think about sounds in words as a starting point, that’s phonemic awareness. Once they can think about sounds in words, you can tie the sounds to the letters.

More to come…

The other two videos in this series are below, in case you want to watch them before I get around to summarising them for blog posts.

Bravo!!!!

It`s a phenomenal posting,I`m going to share it with everyone I know.

David makes us listen,he has passion,knowledge and practicality with his words.

Thanks Alison,

Have already sent to a mother having a problem with her school recommending Guided Reading and Reading Recovery for her child. Her oldest child is quite severely dyslexic, as is her husband. Her second child is not dyslexic, and the last one, in Grade 1, is struggling just like her bigger brother. How can schools not know the evidence by now?

They must ignore the research on purpose and “not give a %&*#.

Thank you for posting these videos and supplemental information. Much appreciated!

Fantastic and helpful notes. I saw these presentations live in Vail in October and took notes and I have been studying and using his material since then, and still your summary helped me gain a better understanding of everything I have learned thus far from David Kilpatrick. Thank you for this work and for sharing it

You’re most welcome, I’m so happy that even someone who was there for the “Real Thing” can get something out of my summary, but it is fast and dense information that, as David himself says, can take a few goes to understand, so I guess that makes sense. Thanks for the nice feedback. Alison

Hi, thanks for this. I’ve seen the link to the lectures shared widely on Twitter but I cannot access it. I always get a message saying the IP address is not recognised. Is this website restricted in some way? I am outside the United States.

Scrap that – they are accessible on your blog but not through Colorado link. Thanks again!

Yay!!!! Great work Alison.

Alison, you referred me to David Kilpatrick’s work last fall when I asked a question about “advanced phonemic awareness.” I not only got the book you recommended above but also his book Equipped for Reading Success which lays out how to teach orthographic mapping and advanced phonemic awareness.

I have come a long way in my understanding of best practice in reading education since earning my master’s in reading over a decade ago. Still, my youngest child was struggling last fall with the explicit, systematic phonics program I was using to teach him to read. He could handle “code knowledge” but would have to decode the same words over and over like it was the first time he’d seen them. Following Kilpatrick’s advice on how to improve his orthographic memory and advanced phonemic awareness has led to a breakthrough for my son. He is reading on grade level now, does not avert his eyes when he sees text in the environment and actually reads signs, and has started to read books for pleasure.

Even with these great results, I have not tackled any of the Kilpatrick videos available on the internet so I was excited to see this post and read your blog. Thanks for the helping hand!

Jennifer, that’s brilliant news, I’m so happy to have been able to help you locate the information you needed to get your son reading well. What a relief it must be to see him pick up a book and read it for pleasure. Well done you! Alison

I. Love. This. So. Much! I have been taking notes as I watch them, but your notes are very clear and succinct! THANK YOU! THANK YOU! THANK YOU! (a fellow word-nerd in the US)

Extremely helpful – it’s still tweaking my brain – I think an important takeaway for adult ESL is that our students, very often fluent readers of their first language, jump straight into self-teaching as they read. Then they end up teaching themselves wrong pronunciations, due not to L1 interference but opaque spelling: ‘deb-t’, ‘receip-t’ and ‘say-ed’ for said. We know that the new words beginners are learning are being stored in long term memory (even before their meaning is fleshed out) based on their sound – and once a word’s sound and meaning are established in LTM, learners have little added trouble with irregular spellings. But once a word is mis-learned, it’s hard to correct, and I’m guessing that this is an underacknowledged part of why we get a lot of students who reach intermediate but are still hard for native speakers to understand easily. We tend to put it down to other things but as teachers we may not be taking enough measures to immunize students from misleading spellings.

Yes, I think one day thanks to this self-teaching, most people who learn English as a second language will pronounce “ed” words like “jumped” with two syllables, as I notice a lot of people in India seem to do. It’s kind of funny that this can make ESL learners sound quite posh/formal, when they pronounce the “f” in “often” and “soften” and say “picture” with the last syllable “ture” rhmying with “pure”. All the Filipinos I know say “comfortable” with four syllables, even one who speaks English better than I do and used to be a Congressman. I also still have to put conscious thought into how to say a few words that I taught myself to pronounce wrong from books, and only years later discovered were wrong. Nobody in my life ever said them e.g. Laos, Archaeopteryx.

We”ve been learning the phonics way of reading, as it”s what they do in uk schools at the moment. Apart from that fact that half our words don”t make any phonetical sense (as we got them from the Romans, Celts, Norse, Saxons, Jutes, Anglos, Normans, whoever else invaded literally or culturally, then dropped letters as the years went by because we couldn”t be bothered to write them, and changed the way said things without changing the spelling..) take heart! Reading and writing nonsense words are encouraged in phonics, as a way of making sure you understand the make up of the word, and aren”t just reading it from memory. So you”re teaching phonics already!

Wonderful information. Thank you!

Did you ever get a chance to do the same for his other videos? Just asking…

Hi Donna, yes, I’ve written a blog post about all three of David Kilpatrick’s Reading in the Rockies videos, just go back through my blog posts and you’ll find them. Alison

This was a great posting regarding Kilpatrick’s work. I’m very new to the idea of orthographic mapping as a teaching approach. I am a reading specialist and trained by an Orton-Gillingham fellow. I utilize the OGS approach with some of my students but my school is very interested in teaching orthographic mapping to the teachers and the other interventionists and I have the joy of doing it. I am trying to wrap my head around the two approaches such as their similarities and differences and orthographic mapping’s effect on students with dyslexia especially orthographic dyslexia taking place in the occipital lobe. Any information you can give me, or a post, study, or website you can direct me to would be amazing

The Reading League YouTube channel is very good, see https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCm9TD9u7xGdRUaGjHkOthxw.

I have been tutoring kids with dyslexia for the past few years using LIndaMood Bells’ Seeing Stars program. I was not surprised to see the LMB Seeing Stars on Mr. Kilpatricks list of programs that don’t produce significant results. I recently began rereading the Seeing Stars course material trying to figure out if I was missing something. After 30 hours of tutoring some of my kids weren’t showing any real improvement. I was thinking about switching to The Barton Reading and Spelling Program.

I was excited to hear Mr. Kilpatrick explain orthographic mapping. It seems like the missing ingredient needed for real improvement. I have worked with many children who improve phonemic awareness and phonological proficiency but it hasn’t led them to become fluent readers.

Are there explicit steps/techniques to teach orthographic mapping or does orthographic mapping develop from phonemic awareness/phonological proficiency?

Kind Regards

Hi Michelle, I think from reading Ehri, Kilpatrick etc that orthographic mapping happens when kids have phonemic proficiency and have been taught the code/phonics, and had enough practice to master the patterns (reading connected text). Spelling is in there somewhere too I suppose, as a means of building robust mental orthographic representations. All the best, Alison

Thanks for the reply. I have ordered Equipped for Reading Success and I look forward to gaining knowledge on how to better meet the needs of our struggling readers.

This really gives those of us “in the trenches” solid information about what do do to help ALL kids learn to read well. Thank you for the videos and the breakdown of them. This information is GOLDEN.

Jeanette, thanks so much for the nice feedback but please tell David Kilpatrick this feedback too, as it’s his information, and I agree, it’s golden, and it’s so amazing that he’s put it in the public domain. All the best, Alison

This was awesome! How do I subscribe to your blog? I am not technologically proficient and discovered this on Facebook somehow.

Hi, you go to this page and fill in the fields: https://www.spelfabet.com.au/sign-up-for-your-free-download.

Thanks for the nice feedback! Alison

Thank you for sharing these videos and summarizing them. A former colleague just shared your webpage with me. When I was the SLD Specialist at the Colorado Department of Education I worked with the Rocky Mountain branch of the IDA to bring Dr. Kilpatrick to the Reading in the Rockies conference. When I left the CDE I was working with him to create a series of short videos modules with several videos ranging from about 3-15 min. each and accompanying PowerPoints based on the content developed in Dr.Kilpatrick’s book (The Essentials of Assessing, Preventing, and Overcoming Reading Difficulties). The goal was for the Modules to be used in bite sized chunks or as a complete series for educators. I left CDE in the spring of 2018, and it appears that they just published the series. Here’s the link to the SLD professional learning page with modules-http://www.cde.state.co.us/cdesped/sd-sld_professional_learning.

We were also working on a similar series based on Dr. Kilpatrick other book (Equipped for Reading Success) that does not appear to have been published yet. Hopefully it will be released soon.

Thank you for appreciating and sharing Dr.Kilpatrick’s videos and for summarizing this important information. Hopefully the series linked above will help in some way…

With Gratitude-

Jill

Hi Jill, sorry to take so long to reply, I got snowed under with clients and then went to a conference on the other side of the country. How great that you were working on professional development with David Kilpatrick, I will take a look at the video link now, I’m sure it’s great. We are really looking forward to having him here later in the year on a national tour. All the very best, Alison

Thanks for the great summaries and links Alison!

I was keen to see more from David Kilpatrick and I was keen to view the videos you mention above Jill. However I can’t access them through the link…the page fails to open / server where the page is located isn’t responding… I’m wondering if this is because I’m based in Australia. Does anyone else outside the US have the same issue or is it just me Thanks!

Thanks!

Hi Victoria, how very strange, I can open it perfectly well and I’m in Melbourne. I am using Mozilla Firefox as a browser, perhaps you’d like to try that? Alison

Hi Jill, has the new series based on Dr. Kilkpatrick’s other book, Equipped for Reading Success, been published yet? Thank you!

And thank you, Alison, for the great notes you took and made available here!

Brilliant summary, thank you!

I have watched a couple of these but appreciate the time you have taken to provide this valuable information.

[…] and Equipped for Reading Success, and you might have also seen him talk online (e.g. here, here, here, here and […]

Try this link to the series; http://www.cde.state.co.us/cdesped/sd-sld_professional_learning

[…] But that bottom part of the rope…English Language teachers typically weren’t trained in that piece. And seeing as this is a blog for the teachers of our youngest students, it is crucial to know the word recognition ins and outs. We have to be able to assess and identify where our students are in the continuum of phonological awareness. We must be able to review a decoding inventory to see what kind of phonics instruction and support our kids need. And we need to be ready to enact strategies to help our students instantly recognize thousands upon thousands of words through a process called orthographic mapping. […]

[…] Reading Eggs offers a free trial period, so anyone can sign in and see the following things for themselves. It first introduces “the sound m, like in mouse” and presents the lower case letter m for children to click on to hear /m/ (I’ll put sounds in slash marks). There’s just letter m at first, and then children must discriminate it from two other letters. There’s no need to link sounds and letters in this activity, so it can be done using visual memory (not the kind of memory used in reading, see this blog post). […]