Low frequency word spelling test

9 Replies

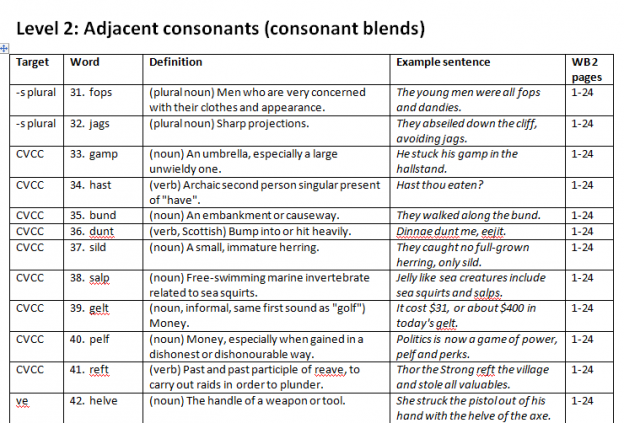

I’ve just made up a free, low-frequency word spelling test which you can download here and use to explore learners’ spelling skills and knowledge.

It’s not a standardised test, so won’t tell you whether a learner’s spelling skills are behind, on a par with or ahead of peers. Its purpose is to focus your attention on the things that matter most for spelling:

- speech sounds (phonemes),

- letter patterns that represent these sounds (graphemes),

- word structure (positions and combinations of sounds in words/syllables),

- parts of speech e.g. “pact” is a noun, “packed” is a verb,

- meaning (especially for homophones like see/sea),

- meaningful word parts (morphemes such as prefixes, suffixes and word stems/roots).

This should help you work out which key skills and knowledge learners already have, and which they need to learn, and thus help teach them to spell explicitly, systematically and effectively.

Don’t do the whole test with anyone, it’s far too long (390 items). Start at your learner’s estimated current skill level, and work forwards if they get words mostly correct, and backwards if they don’t. Stop when you hit a floor (most words too easy) or ceiling (most words too hard).

Teaching ideas

Once you have identified some patterns your learner needs to learn, you can find word lists containing all the patterns here, which you can use to make up practice activities like crosswords/word searches, quizzes, cloze or silly sentence/story activities. The relevant Spelfabet workbooks and/or games, and many other synthetic phonics-type teaching resources, also target these patterns.

Please be careful if choosing teaching resources from the internet or mainstream suppliers. A lot of rubbish is available. Avoid anything that focussing on what words look like, but not what they sound like, or how longer words are built from meaningful parts. Definitely avoid anything that involves choosing a correctly spelt word from among incorrect words (which anyway is a reading task, not a spelling one).

Prioritise activities that involve lots of saying-while-handwriting. Keyboard and moveable alphabet activities are useful, but not as effective as having to physically write letters in the correct order oneself.

Why low-frequency words?

Low-frequency words are used in this test because it’s unlikely that beginners or strugglers will have learnt them visually/by rote, but unlike pseudowords they still have established meanings, usage and spellings, even though many will be unfamiliar even to well-educated adults. Being real also makes the words a bit more interesting than pseudowords (who knew those funny handshakes were called “giving dap”?!).

Australians interested in literacy skill development have been arguing lately about whether we should introduce an early years phonics test like the UK’s Phonics Screening Check, as recently recommended by an expert panel advising the Federal Education Minister.

I’ve written about why I think this is a good idea, as have many others (e.g. here and here) but there’s been quite a campaign against it, particularly from educational academics, literacy teacher organisations and unions.

My new test is partly an exercise in overcoming three objections to the Phonics Check: that the pseudowords on it have no meaning, that they could be spelt more than one way, and that the test is not comprehensive enough (390 items, take that for comprehensive!).

Low frequency words still have meaning

Phonics Check opponents particularly dislike the pseudowords (made up words) on it, which (of course) lack meaning.

Their use is considered invalid because gaining meaning is the purpose of reading.

This is a bit like saying that the written driver’s licence test is invalid because it doesn’t involve any travel, the real purpose of driving.

The boundary between real and pseudo or nonsense words is in any case a porous one, especially in childhood. Any word in the dictionary you don’t yet know is a pseudoword to you, as are the names of people and places you’ve never heard of, words on menus and so on. Acai, maca, togarashi, guindillas, shimeji, arame and espelette are all on the menu of the restaurant I’m taking my friends from France to tonight (ooh la la), and don’t start me on the wine list. Just because I don’t know what the words mean doesn’t mean I can’t read, spell or say them, only to have the correct pronunciation clarified by the remote and elegant Fitzroy waitpersoid.

There are thousands of words that have fallen out of common usage, like “thou” and “aught” and “fain” and “gudgeon”. My Nanna used to say “et” as the past tense of “eat”, like they did on Eastenders, but my Dad only says it occasionally and the rest of us don’t at all. Are words we don’t use any more pseudowords?

Going in the other direction, I googled the first couple of pseudowords from last year’s UK Phonics Check:

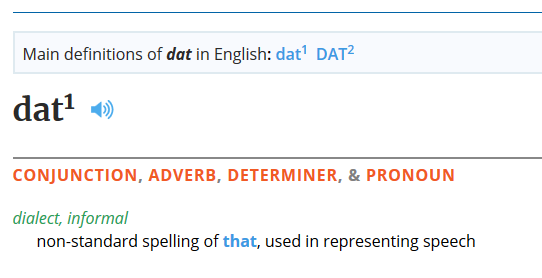

Lo and behold, they both mean stuff. The meaning of “dat” depends on whether you’re talking to someone from biology, education, technology, transport, media and entertainment or elsewhere, see the Wikipedia entry here. According to the online Oxford living dictionaries, in nonstandard dialects, dat is even a high-frequency word.

Likewise, you can find a long list of meanings for “cag” on Wikipedia, though it’s not in the dictionary. But it still means something when you say it to some people in some contexts.

Likewise, you can find a long list of meanings for “cag” on Wikipedia, though it’s not in the dictionary. But it still means something when you say it to some people in some contexts.

Low-frequency words have fixed spellings

Another complaint about pseudowords made by Phonics Check opponents is their lack of established spellings. They argue that “fish” can be spelt “ghoti” and so on, even though this is rubbish, “gh” only represents the sound /f/ at syllable endings and, well, don’t start me.

This objection can’t be levelled at a low frequency word test. Where more than one grapheme is plausible in the relevant word position, the test provides common analogy words clarifying which grapheme is correct (e.g. “braw” is spelt like “law”, “draw” and “straw”). Learners who don’t know the word simply have to know the spellings of the target words, and be able to pull them apart and use the relevant part in a new word to get such items correct.

Spelling is harder than reading

Reading is easier than spelling, since it involves only having to recognise words, not recall them. That’s why most of us are better at reading than spelling. If you’re basing your estimate of what your learner can spell on my test on what she or he can read, you might be over-estimating. Either find a some recent free writing she or he has done, or just start at an earlier level and work your way up. I hope the test makes the task of nailing down the main spelling patterns in our language seem finite, and do-able over time.

Working on spelling patterns during say-and-write tasks focuses learners’ attention on the structure of words and the way sounds and meaningful word parts link to letters and letter patterns. This strengthens the links between the spoken and written versions of the word in a way that doesn’t reliably happen during reading activities, or even during analytic phonics activities, which can be far too much about letters and not enough about sounds.

Our culture tends to think reading is the top literacy priority, and it’s mostly just nerds and pedants who care about spelling. However, research clearly indicates that working on spelling supports reading. Writing words then reading back what you’ve written also makes the reversible nature of our spelling code crystal clear to learners, which again in reading tasks isn’t always apparent to everyone, especially kids who have been taught to look at the picture and guess words, and only sound them out as a last resort (as in Reading Recovery, Guided Reading etc).

Feedback, please!

I hope you find my low-frequency words spelling test interesting and useful, and that it perhaps helps take the heat out of arguments about the benefits and disadvantages of pseudowords, and get on with the task of working out how well learners can sound words out and what other knowledge they have and lack about spelling, in order to teach the missing stuff in an explicit, systematic and effective way.

I’d love your feedback on any aspect of this test, either via a comment on this post or via my other contacts. What do you think?

Wow, you have excelled yourself, Allison! What a comprehensive and interesting list.(It has certainly increased my vocabulary, too!)

I love your wonderful explanations and ability to provide links to articles and evidence. I find your site, blog & Facebook posts invaluable. Thank you so much!

I love this! Working in an environment where decodable reading books and pseudoword spelling tests are not well accepted (although I use them anyway), my program records can now state ‘low frequency word spelling test’! I look forward to trying it out.

Yikes, I hope it lives up to expectations! It’s just something I made up, not a proper standardised test, but I’m sure you know that, and hope it provides you with useful information.

You did it again Alison! I love this. Here we have “strange words” but they are actually real! This is both a spelling test and a vocabulary expansion exercise. I LOVE this! Bravo!

Thanks for sharing this test, Alison. You are a mage.

The utility of the test is clear, however the fun I found in reading the words and being reminded of (or learning for the first time) the meanings was serendipity.

A mage! I don’t even know what that is, but it sounds good! Thank you, for the feedback and the new vocabulary. Obscure words are great, to quote Roy and HG, too many of them is never enough. See you round soon I hope, Alison

Hei Alison ! I love this lovely article !We really have a lot to learn !

Hi, Your low frequency word spelling test is very helpful and its a very good idea for children. It is very good. I really like it. Thank you so much for sharing this information.

[…] https://www.spelfabet.com.au/2018/01/low-frequency-word-spelling-test/ […]