Balanced Literacy: phonics lipstick is not enough

32 Replies

The ACARA media release on the latest NAPLAN data says, “compared with 2016, there is no improvement in average results across the country that is significant”.

Sigh. So many teachers working so hard to improve results, and still 10% of Australian kids are not meeting basic minimum standards. Add to that the many strugglers who didn’t even sit the NAPLAN tests. Sigh.

Teacher-blogger Greg Ashman writes, “The blame for this situation lies squarely with a widespread adherence to bad ideas“. Whole Language – the idea that literacy is “caught not taught” – was a massively bad idea, inculcated into almost our entire teaching workforce at university, but now thoroughly discredited.

What-works-in-education expert John Hattie even puts Whole Language on his pedagogical “disasters” list, see slide 11 here, whereas Phonics Instruction is on slide 21’s “winners” list.

However, the Whole Language pig still has not been put out to pasture where it belongs. Our literacy education brains trust simply applied a bit of phonics lipstick, changed its name to Balanced Literacy, and carried on much as before.

To finally put the Whole Language pig out to pasture, here are five things that need to happen:

1. Replace repetitive/predictable texts with decodable texts

The book-levelling system used widely in schools is still a Whole Language-based one. Its books for absolute beginners are repetitive/predictable texts, full of spelling patterns and word types that children are yet to be taught. Let me write an example book for you now, let’s call it “On The Farm”.

- p1. I can see the cows.

- p2. I can see the sheep.

- p3. I can see the chickens.

- p4. I can see the ducks.

- p.5 I can see the turkeys.

- p6. I can see the dog.

- p7. I can see the cat.

- p8. I can see the farm animals!

I detest such books, my fingers always itch to grab and bin them, especially levels 1-5. Not only are they unspeakably dull, but true beginners can only “read” them by guessing from the pictures. This gives children a false idea of how reading works, and encourages the habits of weak readers, not the habits of strong readers.

The nasty little book I just made up contains the following digraphs: ee, th, ow, ch, ur, ey, ar. What is a child still learning to recognise individual letters supposed to make of them?

Repetitive/predictable books belong in the recycling. They are harmful to many children.

Schools should replace repetitive/predictable books with decodable books, which start off with just a small number of sound-letter relationships and very short words, and then incorporate new sound-spelling patterns and word structures as these are taught.

I take my hat off to schools which have already replaced repetitive/predictable texts with decodables. Throwing out books is hard, and school budgets are always tight, but this a vital step that will prevent a lot of reading failure.

2. Directly teach both early and advanced phonemic awareness

Ideally, children should arrive at school with phonological awareness (awareness that words have structure, as well as meaning), and thus be able to clap or tap syllables, detect and generate rhyme, and identify the first sound in a word (e.g. Mum starts with /m/). The ones who can’t do these things are likely to need extra help learning literacy, and careful monitoring.

Once at school, children need to learn basic phonemic awareness, or awareness of the individual sounds (phonemes) in words, because phonemes are the things represented by letters and letter patterns in our spelling system. Children who can’t pull words apart into their component sounds (segment) will not be able to spell well. Children who can’t combine sounds into words (blend) will not be able to read well.

These skills need to be established in the first year of schooling. A number of useful strategies for teaching them well to young children feature in the new, free, online Sounds~Write Udemy course. It’s meant for parents, but there’s a lot in it that will be useful to early years teachers, therapists and other interested professionals too.

Decodable books can be used in blending instruction, along with other reading and word-building activities containing the sound-spelling relationships and word types that have been learnt. Working on spelling the same kinds of words targets segmenting skills as well.

After children can blend and segment spoken words well, including words with consonant combinations, like ‘camp’ and ‘bench’ and ‘stop’ and ‘bring’, they need to develop advanced phonemic awareness. This is crucial to reading fluency, as it allows children to rapidly build the pool of words they can instantly, effortlessly recognise (via a process called orthographic mapping, which you can read all about in this excellent book by David A. Kilpatrick).

Advanced phonemic awareness involves being able to manipulate sounds in words, for example taking the “l” sound out of the spoken word “helm”, the “s” sound out of “boast”, replacing the sound “s” in “west” with “n”, or doing Spoonerisms (Harry Potter – Parry Hotter etc). It’s a necessary skill in reading word attack when dealing with spellings which represent more than one sound e.g. when the word “dream” changes to “dreamt” we take out the /ee/ as in “sea” and replace it with an /e/ as in “head”.

Most kids develop advanced phonemic awareness as part of the process of learning to decode and encode words, but some children focus too much on letters and not enough on sounds, and benefit from active teaching in this area.

I like to teach advanced phonemic awareness by building and changing words with my moveable alphabet, working from spoken words to spellings (e.g. “make stick, now change it to slick, now change it to slim, now change it to swim” etc) because I worry about missing opportunities to link sounds to spellings. However, the irregularities of written English mean that once you get past “short” vowels you have to plan carefully, as (for instance) when you replace the “s” sound in “wrist” with “p”, you get “ripped”, and the letters no longer work.

There are stacks of one-minute phonemic awareness activities in “Equipped for Reading Success”, also by David A. Kilpatrick, but be aware that he has an American accent, so he can take the “s” out of “fast” and get “fat”, which doesn’t work in Australian or UK English. If you’re as old as me you might also like to drag out your old Rosner program, still available here.

3. Use a synthetic phonics teaching sequence

Teachers often can’t answer questions like “when does your school teach the spelling ‘igh’ as in ‘night'”, as this decision is left up to individual teachers, or year level groups of teachers.

This is an unsatisfactory state of affairs, because it means that there is no simple way of knowing what has already been taught to each group of children and what hasn’t, or ensuring that all the main patterns are taught systematically. If a child can’t spell words with ‘igh’ as in night, is that just because they haven’t been taught yet? Or have they done it every year for three years, and still can’t remember it?

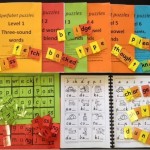

Each primary school needs a synthetic phonics teaching sequence, which should be the same one used in its decodable books. Examples are:

- the Little Learners Love Literacy sequence

- the Letters and Sounds/Get Reading Right/Pocket Rockets sequence

- the Jolly Phonics/SA SPELD books sequence

- the MultiLit family of programs, such as PreLit, InitiaLit and MiniLit.

- the Sounds~Write/Phonic Books sequence

- the Phonics International sequence:

These ensure that all major spelling patterns are explicitly and systematically taught and reviewed in the first three years of schooling, both in reading and spelling tasks, and that spelling activities teach a pattern at a time to mastery, and don’t overload children with too many patterns at once.

Beyond this, it would be helpful if all schools had a clear sequence for teaching harder spelling stuff like lower-frequency consonant spellings, homophones, and word parts like prefixes, suffixes and Latin and Greek word roots/stems.

4. Scrap rote-learning of high-frequency word lists

Lots of the words on high-frequency word lists can be easily decoded once basic spelling patterns are learnt. Why on earth is any child being asked to visually memorise words like “it” and “in”, as per the “Golden Words”?

Most decodable books address the issue of high-frequency, irregularly-spelt words by including a few important words like “to” and “the” and “was” early in the sequence even though they include sound-spelling relationships not yet taught. The Little Learners books call these words “heart words”, Get Reading Right calls them “camera words”. Whatever you call them, high-frequency words with funny spellings are addressed in synthetic phonics teaching approaches. There is no need to memorise high-frequency word lists by rote.

Encouraging children to rote-memorise high-frequency word lists can lead to considerable confusion about sound-letter relationships. Teachers tell children in alphabet lessons that the letter S sounds like “s”, but in the Golden Words, the only sound represented by the letter S is “z” (in the words “is” and “was”) and there are no words in the Golden Words where the letter S is pronounced “s”. The only sound represented in the Golden Words by the letter F is “v” (in the word “of”). And so on.

5. Use current, evidence-based models of reading

Marie Clay, who said words should only be sounded out as a last resort*, is a guru to many literacy leaders in schools. However, her model of reading was a Whole Language one, and simply wrong. We do not decode words from context.

This means it’s time to take the multi-cueing/three-cueing model of reading off school pinboards and out of overheads and handouts, and put it in the recycling too. And most importantly, stop assessing and teaching according to this model.

Recycle your Running Records. They’re slow, subjective, and classifying and counting miscues is just a waste of precious time. The bizarre Whole Language idea that it’s better to misread “horse” as “pony” than “house” doesn’t even pass the pub test, much less stack up with the current reading science. There are fast, objective, free tests that do available here.

Current, evidence-based models show that word reading draws on knowledge of sounds (phonology), letters/spelling patterns (orthography) and vocabulary (semantics), and that the context processor is not part of the word reading “triangle” system. The following diagram is from p140 of the 2017 book “Language at the Speed of Sight: How we read, why so many can’t and what can be done about it” by Prof Mark Seidenberg:

Good readers read words accurately whether they are in proper sentences, gibberish sentences, or standing alone. Poor readers can’t, which is why they end up guessing and making lots of mistakes.

Reading for meaning of course involves more than just reading words, and scientific evidence on reading comprehension has consistently supported the Simple View of Reading:

Reading Comprehension = Decoding X Listening Comprehension.

If you want a recent scientific paper with references on the validity of this model, click here.

Reading comprehension combines one’s decoding skills and one’s listening comprehension. Learners who have weak decoding, and/or weak listening comprehension, will have weak reading comprehension. To work out what to do about that, it’s necessary to assess which part of the equation is weak:

- Is it just decoding? (dyslexia-type difficulties)

- Is it just listening comprehension? (hyperlexia, typically seen in kids on the Autism Spectrum, or kids with poor listening skills who’ve been taught to decode well)

- Is it both? (language delay or disorder).

Once the source(s) of the problem is/are identified, it’s possible to work out how to address it/them, through listening/language therapy and/or intensive systematic phonics.

I hope everyone worried about the latest NAPLAN results will ask people involved in early years education whether their schools use decodable books, teach both basic and advanced phonemic awareness, follow a synthetic phonics teaching sequence, skip rote-memorisation of high-frequency word lists, and are using models of literacy which stack up with the reading science. And if not, how and when this is going to change.

* Regarding the process of word identification, Marie Clay wrote: “[Beginning readers] need to use their knowledge of how the world works; the possible meanings of the text; the sentence structure; the importance of order of ideas, or words, or letters; the size of words or letters; special features of sound, shape, and layout; and special knowledge from past literary experiences before they resort to left to right sounding out of chunks or letter clusters, or in the last resort, single letters. Clay, M.M. (1998). An observation of early literacy achievement. Auckland, NZ: Heinemann. Quoted in Seidenberg, M: “Language at the Speed of Sight, 2017.

Wonderful! This provides a great explanation, with cited evidence, which is really helpful when trying to convince others. Thank you.

Another great blog Alison, thank you. Re the comprehension, what testing would you suggest to best “pull apart” the comprehension measurements? Lots of comprehension tests, that I I know of, rely heavily on decoding, so results for comprehension come back low. As you say, its important what the exact issue is but I’m not sure of the best assessment and schools often do the NEALE.

Thank you.

Thanks for the nice feedback. You need a speech pathologist to assess listening comprehension, the usual test for school-aged children and teenagers is the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals (CELF-4 or the new CELF-5), but there are other standardised language assessments which yield a Receptive Language/listening comprehension score. A child who does poorly on the Neale or other test of reading comprehension might be doing so because of poor decoding or poor language comprehension, or both. So its results don’t really help with planning intervention.

I don’t think anything is new in this article. There are bits of many programs in this article that we know and have used over time. I think having the freedom to address the needs of your students in your class as an experienced teachers is definitely a must. I know from working in the coast in an affluent area and now working in a remote school my program has dramatically changed. I use a variety of different bits of different programs, but never gave up my explicit phonics program even when my school wanted me to do that (due to L3). Teachers need flexibility and not a one size fits all approach.

No, I’ve said this all before one way or another, and so have so many people. But one thing I learnt in a brief foray into politics (local government and I worked for the Vic Greens for a while) is that you have to keep saying the same thing over and over if you want it to be heard by more than just a few people. I know teachers value flexibility and innovation, but as Pamela Snow points out, if a surgeon or a pilot said “I know there is a very specific procedure I am meant to follow here to get the best results, but I’m going to mix and match some stuff I learnt at uni decades ago, a few things I made up myself and some of the procedure with the best results” there would be uproar.

I remember my first introduction to whole language all too well. It was 1990, I was in my first year of teaching at uni and my language lecturer was Chrystine Bouffler (Spell by writing: Bean & Bouffler 1987). The whole year was devoted to promoting Whole language. I was so confused. I could see the logic behind the theory but I could also see that it was reliant of children willing to make an effort to self correct and I knew the majority either couldn’t or wouldn’t work that way. I made myself very unpopular with Ms Bouffler that year, questioning her research and theories (probably in an immature manner – I was only 18) and getting no satisfactory response. At one point I got so frustrated that I loudly told her she was risking a generation of near illiterates (see, immature). The funny thing though was our final essay. We were set a question that obviously expected us to use whole language theory in our response but there was wiggle room for other theories. There were 160 students in our year. Only 15 people passed and all of them were people like me who avoided the promoted approach because our research couldn’t supply enough solid data to support it. Except in a few cases where the method meets a specific need, I have been vocal against it ever since. No one ever listened. Now, we even have teachers who we’re never taught phonics, spelling, punctuation or grammar. I’ve recently corrected half yearly reports, many were very poor quality. I’m glad to see a shift in approach but how are we to repair the damage when the people we must rely on to drive it don’t have those skills themselves?

Good question, a big focus on building teachers’ skills. A lot of parents say that they learn stuff about spelling themselves when they bring their kids to sessions so I have no doubt that teachers could learn too, if only they had the time and access to the right courses. Alison

Have you come across SSP (Speech Sound Pictures)? I’m using Miss Emma’s resources for homeschooling. It was a little different to get my head around first up but we’re loving it now. Phonemic based and relates to the IPA.

Hi Rach, yes I have come across SSP, but I do not myself promote it, and am not in a position to discuss why in a public forum like this. All the best, Alison

I’m sorry, but you are incorrect on almost all points. I hope Australian teachers are more literate than you are. While others are thanking you for citing research, the fact is that you misquoted research.

Dear Christy, thanks for your comment, would you please tell me the main things you disagree with me about, and what evidence you have to support your view? And which research you think I have misquoted? As John Maynard Keynes recommended, I change my mind when the facts change, and if there are facts I am not taking into account that you know about and I don’t, then please tell me what they are.

I am 71 years old and was in education for 40 years. This argument will not die. Most kids learn to read in spite of our “beliefs.” Put all strategies in your teacher backpack and figure out what you need for that student. What will make him LOVE to read. I am a great fan of Marie Clay. I see reading as a process like swimming, Interest, demonstrate,coach,encourage, enjoy.

Hi Loretta, it’s quite true that most learn despite teaching methods and ideas, but the ones that concern me are the ones I work with, the strugglers, who really need structured explicit synthetic phonics and often aren’t getting it unless their parents can pay for it. I’m sure Marie Clay was a very nice, well-meaning woman but the scientific research on Reading Recovery shows it’s not very effective. Your analogy with swimming is very apt, but when we teach children to swim, we take them into the shallow pool and give them noodles kickboards and gradually introduce them to skills like putting their face in the water and floating, we don’t throw them straight in the deep end. Likewise, we should be giving little kids decodable books that gradually introduce sound-letter relationships, not throwing them straight in the deep end of repetitive texts full of spellings they have never been taught, or expecting them to read “real books” before they have learnt all the code required.

Thankyou so much for your excellent article which makes so much sense when I think about what happened to my child with dyslexia. His school district here in CO USA used Whole Language in K, then a couple years later branded the same instruction as “Balanced Literacy”. This year the literacy director is calling it “Interactive Literacy” which seems to be about the same. Can you tell me what is Interactive Literacy? and how is it meant to be different from the last approach they used, Balanced Literacy ? Just FYI, I pulled my child out and he went for three years to a private school that taught with an Orton-Gillingham approach. He can know read, but never as fluently as if he would have if he had received this MSL Structured literacy in K.

Thanks for your nice feedback. I have never heard of “interactive literacy” but maybe that will be the next shapeshift of Whole Language. If it still involves doing the same old things and not breaking the code down for learners, it will deliver the same results. Great to hear you saw the writing on the wall and found a school that could help your child learn to read. Too many kids don’t get that opportunity and that’s what we have to change. Alison

Great blog post Alison. It is beyond frustrating to be a literacy educator right now and it is fabulous to read your posts to remind myself that the research and evidence is on my side.

Thank you Alison for you continued posting and blogging on systematic synthetic phonics and warning educators about the dangers of adhering to a balanced or whole language approach. I regularly feel like a fish out or water here in NSW amongst the Early Action for Success schools with L3, Reading Recovery, three cueing techniques, and only PM benchmark books in the reader boxes. It was the disconnect that RR displayed in many Year 1 classes that led me to a Masters in Inclusive Education and I am so encouraged that there are many like you who are passionate about scientific-based reading research. Keep up the good work! I’ll keep reading and sharing your blog!

This article was awesome and cemented that our school system is on the right track as we do “use decodable books, teach both basic and advanced phonemic awareness, follow a synthetic phonics teaching sequence, skip rote-memorisation of high-frequency word lists, and are using models of literacy which stack up with the reading science

Nice one, love your work, hope and expect you are seeing great results! Alison

Excellent article Alison. My 10 year old son is in grade 5 in a Melbourne school and has suffered from ALL of the problems you discuss here. Although he is an excellent reader, he is a very poor speller and consequently, his writing and grammar are not great either. His school never focussed on letter formation at lower primary and he doesn’t do cursive writing. (HE is also a lefty which I think made it harder for him.) His teacher has basically told him to give up and print. I also think his reading is helped by the fact that often he reads the gist of things and is intelligent enough to work things out from context. I often find that when he reads aloud he has trouble reading each word accurately.

My husband and I are at the stage where we realise we will have to pay a professional to work one on one with him and back fill what he doesn’t know or he will never catch up. We’re in Maribyrnong. Where is the best place to start?

Hi Kathleen, you could try Learn Quick Smart in Moonee Ponds (www.learnquicksmart.com.au), or see if you can find an LDA tutor in your area who can help him with spelling. There is an online search function here: https://www.ldaustralia.org/tutor-search.html. Alison

Hi Alison I am interested in your views on grade retention. I am working with a child who is in Prep, is younger than most of his cohort and has a severe speech sound disorder resulting in very poor phonological awareness skills. The school is pushing for him to advance to year one while his mother and I are both of the view that maybe another year in Prep will give him time to make further gains with his speech which will in turn aid phonological awareness. Do you know of any research in this area? Thanks

Hi Alison, I am not an expert in this area, but John Hattie has done a meta-analysis of retention studies and you can find it here: http://www.nwarctic.org/cms/lib/AK01001584/Centricity/Domain/40/Retention-Visible%20Learning%20by%20John%20Hattie.pdf. I think his main message is that retention is not generally recommended, but this is research about kids across the system not just younger-than-most Preps with phonological problems. Is the school offering a systematic, explicit synthetic phonics program in Prep that the child hasn’t already done this year, and which will allow this child to establish missing foundational skills next year? Is it backed up by a good Tier 2 system? If so then another year in Prep might be great, but if they are doing PM readers, Golden Words, initial phonics etc then I’m not sure there would be strong arguments for repeating from a reading and spelling point of view.

“Advanced phonemic awareness” – you are the first person to put a name to what I have been suspecting for some time is an extreme challenge for my youngest child. He was learning to read at a steady but very slow pace with a systematic, explicit synthetic phonics program I was using and I suspected there was an issue. I recently started using materials with him that teach from the sounds (linguistic phonics) but also include a lot of phonemic manipulation exercises as you described above that will help him in reading word attack. This has really helped a lot though we still have more work to do.

I appreciate the reference to David Kilpatrick, I will look up his work. Do you know of others who write about advanced phonemic awareness? And what to do when a child doesn’t learn it on his own through the learning to read process? I used to teach in the public schools and was trained as a Balanced Literacy teacher. I have to wonder how many children would benefit from this type of explicit instruction.

Hi Jennifer, I think so few people really understand the structure of spoken words in education that this is a massive area that is critical to many children’s success, but largely neglected. David is part of The Reading League and they have a YouTube channel that is worth a look: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCm9TD9u7xGdRUaGjHkOthxw. I had a lot of old Jerome Rosner stuff years ago that I’d use with kids who were really stuck to good effect, but in too many moves I can’t now find it. I have Kilpatrick’s program “Equipped for Reading Success” and am gradually getting my head around it. We think the spellings are what makes English hard to read and write, but in fact for many kids it’s understanding the sounds, and that’s lost in typical phonics programs.

I so appreciate your reply, Alison. You have a wealth of resources on your website and I could hardly tear myself away this weekend. Following other people’s journey through the field of reading instruction helps me to identify the holes in my training and understanding. There is so much to unlearn and learn anew when you’ve been trained in Balanced Literacy.

Hallelujah!

According to Dr. David Kilpatrick (SUNY Cortland) in his book Equipped for Reading Success phonological awareness can be trained. This is especially important for the 30% of humans who are genetically predisposed to have difficulty with these skills. Decodable books are effective and important but that does not require one to throw out leveled readers. Students can still enjoy them. Filling in the words they are not yet able to read will not teach them to read those words but it does not do damage and neither does repeated exposure to the high frequency words they can. Systematic phonics instruction can be happening simultaneously with these other experiences. A healthy diet is not destroyed by the occasional ice cream cone which can provide a pleasurable experience. Yes it is important to know which is which but we do not have to become inflexible fanatics. I use phonics (Wilson Fundations) and the spelling rules outlined in Uncovering the Logic of English by Deise Eide as well as the phonological awareness activities in Dr.Kilpatrick’s book to teach struggling readers but I also allow them other reading experiences that are not part of a program. I hesitate to call this a balanced approach due to the negative connotations that word now has but I believe that is what it is.

I agree that it’s important not to be too rigid, but the books that I’d like to throw out are the ones for real beginners that require them to guess words from pictures. That’s not reading, that’s guessing.

Thank you for the great article. I just wanted to let you know that the Rosner link is not working. I’d love to see his program if you have a different link as I hear so many great things about it.

While I agree with much of the article, I believe that “we do not decode from context” is an overstatement. Context is language. Vocabulary and sentence structure inform our decoding, especially at higher levels. For example, “That book was a great read” versus “I read that great book.” Also, miscue analysis helps me understand how language might be interacting with decoding. For example, if a child decodes the word “spring” but leaves off “ing” on verbs the issue may not be a lack of decoding skills but rather limited morphological knowledge. I support that decoding as a last resort and repetitive language books send the wrong message to beginning readers, however. (I am a speech-language pathologist and certified reading teacher.)

I’m here in the U.S. and my district is promoting Letter Land as part of our curriculum. Do you have an opinion in regard to the program?