What helps kids read and spell multisyllable words?

19 RepliesVirus rules permitting, the Spelfabet team will present a workshop at the Perth Language, Learning and Literacy conference on 31st March to 2nd April this year.

The title is “Mouthfuls of sounds: Syllables sense and nonsense”, so I’m now scouring the internet for research on how best to help kids read and spell multi-syllable words.

Teaching one-syllable words well seems to be going mainstream

Lots of people seem to have now really nailed synthetic phonics, and are using and promoting it in the early years and intervention (yay!). It’s become so mainstream that I just bought three pretty good synthetic phonics workbooks (Hinkler Junior Explorers Phonics 1, 2 and 3) for $4 each at K-Mart (in among quite a lot of dross, but it’s a start).

Many synthetic phonics programs and resources focus mainly on one-syllable words, most of which only contain one unit of meaning (morpheme), apart from plurals like ‘cats’ (cat + suffix s), past tense verbs like ‘camped’ (camp + suffix ed), and words with ancient, rusted-on suffixes like grow-grown and wide-width.

Multisyllable words contain extra complexity

Synthetic/linguistic phonics programs which target multisyllable words, including spelling-specific programs, vary widely in their instructional approach. Multisyllable words aren’t just longer (in sound terms, though words like ‘idea’ and ‘area’ are short in print), they contain extra complexity:

- Most contain unstressed vowels. When reading by sounding out, we apply the most likely pronunciation(s) to their spellings, often ending up with a ‘spelling pronunciation’ that sounds a bit like a robot, with all syllables stressed. We then need to use Set for Variability skills (the ability to correctly identify a mispronounced word) to adjust the pronunciation and stress the correct syllable(s).

This can mean trying out different stress patterns, and sometimes also considering word type – think of “Allow me to present (verb) you with a present (noun)”. Homographs often have last-syllable stress if they’re verbs, but first syllable stress if they’re nouns.

- Prefixes and suffixes change word meaning/type, they don’t just make words longer e.g. jump (simple verb), jumpy (adjective), jumped (past tense/participle), jumping (present participle), jumpier (comparative), jumpiest (superlative), jumpily (adverb), and the creature you get when you cross a sheep with a kangaroo, a wooly jumper (agent noun, ha ha). I write ‘wooly’ not ‘woolly’ (though both are correct), because it’s an adjective not an adverb: wool + adjectival ‘y’ suffix, as in ‘luck-lucky’ and ‘boss-bossy’, not wool + adverbial ‘ly’ suffix, as in ‘real-really’ and ‘foul-foully’.

- Word endings often need adjusting before adding suffixes: doubling final consonants (run-runner), dropping final e (like-liking) and swapping y and i (dry-driest). Kids need to learn when to adjust, and when not to, so they don’t over-adjust and end up with ‘open-openning’, ‘trace-tracable’, and ‘baby-babiish’.

- Co-articulation (how sounds shmoosh together in speech) often alters how morphemes are pronounced when they join – compare the pronunciation of ‘t’ in ‘act’ and ‘action’. Sometimes this also results in spelling changes e.g. the ‘in‘ prefix in ‘immature’, ‘imbalance’, ‘impossible’ (/p/, /b/ and /m/ are all lips-together sounds), ‘illegal’, ‘irrelevant’, ‘incompetent’ and ‘inglorious’. ‘In’ is pronounced ‘ing’ at the start of words beginning with back-of-the-mouth /k/ and /g/, like the ‘n’ in ‘pink’ and ‘bingo’.

- Reading longer words requires a lot more trying-out different sounds, particularly flexing between checked and free (or ‘short/long’) vowels, as in cabin-cable, ever-even, child-children, poster-roster, unfit-unit. Vowel sounds in base words often change when suffixes are added, e.g. volcano-volcanic, please-pleasant, ride-ridden, sole-solitude, study-student, south-southern (word nerds, look up Trisyllabic Laxing for more on this).

- Many word roots, like ‘dict’, ‘spect’, ‘fract’ and ‘path’, aren’t English words in their own right, but still mean something. However, teaching morpheme meanings may not have much benefit for decoding, fluency, or even vocabulary or comprehension (see Goodwin & Ahn (2013) meta-analysis of morphological interventions).

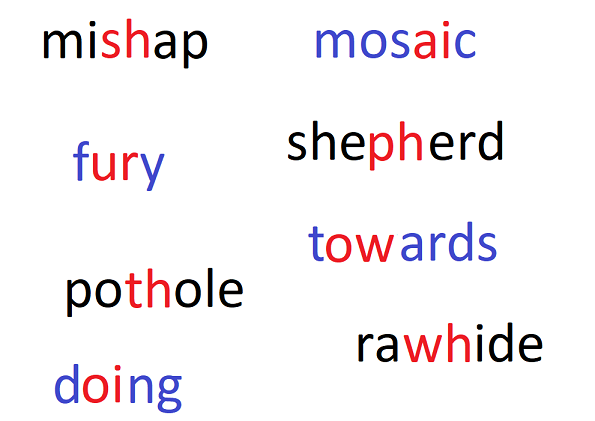

- Spellings that look like digraphs sometimes represent two different sounds in different syllables e.g. shepherd, pothole, area, stoic, away, koala (see this blog post), again requiring flexible thinking about how to break words up.

I use the Sounds-Write strategy to help kids read and spell multisyllable words, which doesn’t teach spelling rules, syllable types, or other unreliable, wordy things. The Phono-Graphix and Reading Simplified approaches are similar.

However, Sounds-Write doesn’t have an explicit focus on morphemes (well, maybe their new Yr3-6 course does, I haven’t done that yet), so I’ve also been using various morphology programs and resources: books by Marcia Henry, Morpheme Magic, games like Caesar Pleaser and Breakthrough To Success, Word Sums, the Base Bank, and the Spelfabet Workbook 2 v3 for very basic prefixes and suffixes. However, I need a better grip on the relevant research and its implications for practice.

Video discussion on syllable issues

There’s an interesting video of a discussion about research on syllable issues between Drs Mark Seidenberg, Molly Farry-Thorn and Devin Kearns (you might know his Phinder website) on Youtube, or click here for the podcast.

I always want to shout “Speak up, Molly!” when watching these discussions, because she doesn’t say much, but what she does say is usually great. Near the end of this video, she summarises the implications for teaching. Here’s my summary of her summary:

- Explicit teaching about syllable types takes time, adds to cognitive load and takes kids out of the process of reading, so try to keep it to a minimum in general instruction.

- Children who aren’t managing multisyllable words after general instruction may need to be explicitly taught vowel flexing, and/or about syllable types.

- Group words in ways that make the patterns/regularities and clear, and help children practise vowel flexing.

- It can be helpful for teachers to know a lot about syllables, rules etc, but that doesn’t mean it all needs to be taught.

Dr Kearns then goes further, saying he suggests NOT teaching syllable types and verbal rules, apart from basic things like ‘every syllable has a vowel’. Instead, he recommends demonstration of patterns and then lots of practice. Many children with literacy difficulties have language difficulties, so verbal rules can overwhelm/confuse them, and aren’t necessary when skills can be learnt via demonstration and practice.

I’m now trying to get my head around his research paper How Elementary-Age Children Read Polysyllabic Polymorphemic Words (PSPM words) without getting too overwhelmed/confused by terms like ‘Orthographic Levenshtein Distance Frequency’, ‘Laplace approximation implemented in the 1mer function’ and BOBYQA optimization’, and having to go and lie down.

The 202 children studied were in third and fourth grade, attending six demographically mixed schools in the US. This was quite a complex study with multiple factors and measures, so I won’t try to summarise the methods and results, but instead skip to what I think are the main things it suggests for teaching/intervention (but please read it yourself to be sure):

- Strong phonological awareness helps kids read long words, though it may make high-frequency words a little harder, and low-frequency words a little easier. It may help kids link similar sounds in bases and affixed forms, e.g. grade-gradual.

- Strong morphological awareness also helps kids read long words. It’s more helpful than syllable awareness. Processing a whole morpheme is more efficient than processing its component parts, and since morphemes carry meaning, they may help with vocabulary access.

- It helps to know sound-spelling relationships and how to try different pronunciations of spellings in unfamiliar words, especially vowels.

- Having a large vocabulary helps too, as children are more likely to find a word in their oral language system which matches (more or less, via Set for Variability) their spelling pronunciation. Children with large vocabularies might also persist longer in the search for a relevant word.

- High-frequency long words, and words with very common letter pairs (bigrams), are easier to read than low-frequency words and ones with less common letter pairs.

- Most kids learn to process morphemes implicitly in the process of learning to read long words, but struggling readers have more difficulty extracting information implicitly, so many need to be explicitly taught to do this. Strategic exposure and practice is more likely to produce implicit statistical learning than teaching rules, meanings etc.

- It’s easier to process base words that don’t change in affixed forms (e.g. appear-appearance) than ones that change a bit (e.g. chivalry-chivalrous). Kids with weak morphological awareness may need to be taught awareness of both.

- Knowing many derived words’ roots (e.g. the ‘dict’ in ‘contradict’, ‘predict’, ‘dictionary’, ‘dictate’, ‘addict’, ‘valedictory’, and ‘verdict’) makes it more likely the reader will be able to use root word information to read long words.

- Knowledge of orthographic rimes doesn’t seem to help kids read long words. Kearns calls these ‘phonograms’: the vowel letter and any consonant letters following it in a syllable e.g. the ‘e’ and ‘ict’ in ‘predict’, or the ‘uc’ and ‘ess’ in ‘success’.

- This study focussed on reading accuracy but not fluency, and didn’t measure prosodic sensitivity or Set for Variability skills. Further research is needed on these.

If you have insights on any of the above, please write them in the comments below.

When digraphs ain’t digraphs

18 Replies

When working on decoding and spelling two-syllable words with a student, I often use the TRUGS deck 4 cards, which include the word “mishap”.

Invariably, my students parse this as “mish-ap”, rhyming the first syllable with “fish”.

At first this made me want to get out my correction tape and replace “mishap” with a word that would give them more immediate syllable-parsing success.

Then I realised “mishap” provides a perfect opportunity to discuss how spellings that look like digraphs aren’t always digraphs, so we also need to think about what word parts mean and how letters might work separately when tackling unfamiliar words. (more…)

Try learning a new alphabet yourself

1 Replies

I have a quick workshop activity which gives adults a small taste of what it’s like for children beginning to learn to use a new alphabet.

I’ve decided to make it available to my gentle blog-readers to try out with colleagues, at workshops etc., to help make the point that learning new, abstract symbols is very difficult.

You can download the worksheets for this activity here. The pictures are free-to-use ones from the internet, thanks so much to the generous photographers.

The activity takes about five minutes. There are four tasks:

Task 1

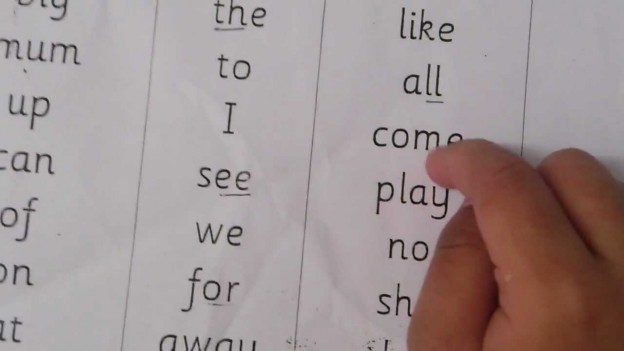

Filling gaps in sentences by listening to them being read aloud and copying the relevant high-frequency words. Five-year-olds are often asked to memorise the 12 “golden” words used (a, an, be, I, in, is, it, of, that, the, to, was) as one of their first literacy tasks when starting school. Typically adults find they can do this task quickly and without having to think very hard. (more…)

Filling gaps in sentences by listening to them being read aloud and copying the relevant high-frequency words. Five-year-olds are often asked to memorise the 12 “golden” words used (a, an, be, I, in, is, it, of, that, the, to, was) as one of their first literacy tasks when starting school. Typically adults find they can do this task quickly and without having to think very hard. (more…)

Dissing, choosing and teaching sight words

29 Replies

The Developmental Disorders of Language and Literacy Network (DDOLL) has recently been having an interesting discussion about whether systematic explicit phonics advocates have been dissing sight words too much. Not everything is about me, but I think I might be one of the possible-over-dissers – see for example my blog posts here, here and here.

A few days ago, Professor Anne Castles of Macquarie University, who’s on the Learning Difficulties Australia (LDA) Council with me, wrote a guest blog post on the Read Oxford website called “Are sight words unjustly slighted?”, which I encourage you to read.

A few days ago, Professor Anne Castles of Macquarie University, who’s on the Learning Difficulties Australia (LDA) Council with me, wrote a guest blog post on the Read Oxford website called “Are sight words unjustly slighted?”, which I encourage you to read.

Prof Castles has a brain like a planet and a string of relevant publications longer than both my arms, so we need to take what she says seriously.

What is a sight word?

To Prof Castles, for teaching purposes, sight words are specific tricky words that children are likely to encounter regularly, taught with a focus on the word level rather than the sound-letter relationships. However, she notes that “sight words” are often confused with the process of reading words “by sight” rather than having to sound out every word. (more…)

Predictable or repetitive texts

6 Replies

I've made a new video about predictable texts, sometimes called repetitive texts.

These are short books typically given to little kids when they first start school, and which they take home to read with their parents.

Each page usually contains a sentence and a picture. The same sentence frame repeats on each page, with just one or two words changed to reflect the new picture.

Children often "read" these books by guessing from pictures, first letters and context, i.e. they engage in reading-like behaviour, but they're not actually reading. Often it's only when texts get more complex that adults notice that they can't actually decode.

Let's have a look at some example repetitive, predictable texts, and compare their spelling patterns and syllable structures with decodable texts, and see what they look like to a beginning reader.

If you get this blog post by email and the embedded video below has dropped out, click here to view it online.

To find a list of decodable books, click here.

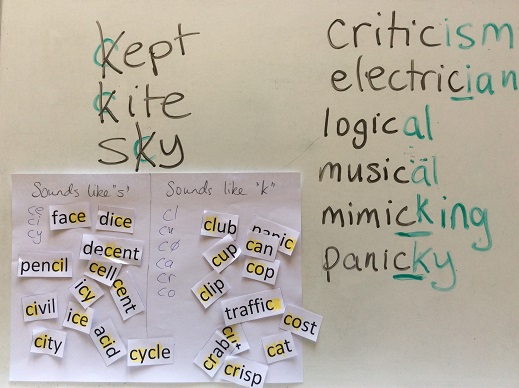

C that sounds like “s”

10 Replies

The letter C can represent the sound "k" as in "cut" or the sound "s" as in "cent".

Teaching learners how this works and why it's a good thing when we start adding suffixes to words can be tricky, especially if they don't really understand "if-then" sentences yet.

Here's a 6 minute video I made about one way to do it.

Note that the spelling CC is sometimes followed by a letter E but the sound is still "k", e.g. soccer, sicced (as in "I sicced the dog onto the burglar and she ran off"). CC is like other doubled letters, its main purpose is to tell you to say a "short" vowel before it, as in raccoon, Mecca, piccolo, broccoli and buccaneer. Typically, but not always, we write CK instead of CC.

The spelling C+C might also represent a "k" sound at the end of one syllable followed by a "s" at the start of the next syllable, as in "accede", "accent", "accept", "access" and "coccyx".

Also, either a single or double C might represent a "ch" sound in some Italian-origin words e.g. cello, Botticelli, bocce (click here for more).

Echo reading

13 Replies

I wasn’t sure whether to laugh or cry recently upon discovering a video from the University of Canberra called “Echo Reading”.

OK, I thought, Whole Language/Balanced Literacy has finally jumped the shark.

In this video, an adult reads a book that is too hard for a student aloud, pausing after each sentence for the student to repeat the sentence:

If you are the sort of person inclined to notice things such as emperors not having any clothes, you will have noticed that all the student has to be able to do to succeed at “Echo Reading” is be able to repeat spoken sentences. They don’t even have to look at the text.

In Speech Pathology and linguistics circles, we call this skill “verbal imitation”. Not “reading”. (more…)