Dissing, choosing and teaching sight words

29 Replies

The Developmental Disorders of Language and Literacy Network (DDOLL) has recently been having an interesting discussion about whether systematic explicit phonics advocates have been dissing sight words too much. Not everything is about me, but I think I might be one of the possible-over-dissers – see for example my blog posts here, here and here.

A few days ago, Professor Anne Castles of Macquarie University, who’s on the Learning Difficulties Australia (LDA) Council with me, wrote a guest blog post on the Read Oxford website called “Are sight words unjustly slighted?”, which I encourage you to read.

A few days ago, Professor Anne Castles of Macquarie University, who’s on the Learning Difficulties Australia (LDA) Council with me, wrote a guest blog post on the Read Oxford website called “Are sight words unjustly slighted?”, which I encourage you to read.

Prof Castles has a brain like a planet and a string of relevant publications longer than both my arms, so we need to take what she says seriously.

What is a sight word?

To Prof Castles, for teaching purposes, sight words are specific tricky words that children are likely to encounter regularly, taught with a focus on the word level rather than the sound-letter relationships. However, she notes that “sight words” are often confused with the process of reading words “by sight” rather than having to sound out every word.

However, if Wikipedia is a valid indication of what most people think, most people think “sight words” are commonly used words that young children are encouraged to memorise as wholes by sight (my italics).

Experts on the SpellTalk listserve say sight words are words a reader can immediately recognise, and that the goal of reading instruction is to make all words into sight words.

The LDA website glossary says they’re “words that a reader recognizes without having to sound them out. Some sight words are ‘irregular’, or have letter-sound relationships that are uncommon. Some examples of sight words are you, are, have and said”. Which is kind of like having a bob each way, if the LDA glossary compilers will excuse my saying so.

Sigh. Here we are, back in Alice’s Wonderland, where a word may mean whatever I choose it to mean. Is the “sight” in “sight words” a property of the words, or a property of the reader?

For the purposes of this blog post, let’s go with Prof Castles’ definition – words containing tricky spellings that learners can’t successfully sound out.

How should sight words be taught?

Prof Castles says that sight word training is effective when the learners can already recognise letters and know that they represent sounds, and the training focusses on the words’ pronunciation, the identity and order of the letters, and includes lots of repetition.

She says children should not be encouraged to identify words by their overall shape or by salient visual features, and that teaching should always happen in the context of systematic, explicit phonics teaching.

The recommended teaching methods for sight words involve a great deal more than just using the sense of sight. When we pronounce words we use our hearing, and our kinaesthetic sense as we feel sounds in our mouths, and if we also write the words we feel the shapes of the letters in our hands. I’d probably call this multisensory teaching/learning, except that’s another Wonderland term. (No! Not the sandpaper! Not the shaving cream!)

If we are focussing on pronunciation and letters in sight words, then perhaps children should learn the similarly trickily-spelt words “to” and “do” together. Perhaps throw in “who”, another very common word with the same final vowel sound and spelling, just for laughs.

But would that be “teaching phonics” not “teaching sight words”? The boundary starts looking extremely unclear.

High-frequency words are confused with sight words

I don’t observe the sort of teaching Prof Castles recommends happening much in schools.

Most schools seem to agree with the Wikipedians that the term “sight word” is a synonym for “high-frequency word to be learnt by sight”.

High-frequency words are words people use a lot, not necessarily words with tricky spellings.

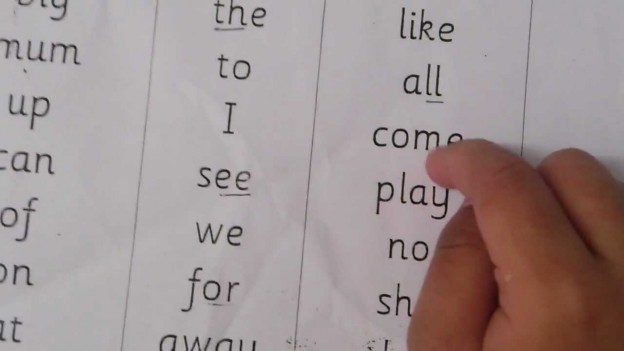

There are various high-frequency word lists, but for the purposes of this discussion let’s use the example of the Oxford Wordlist, since Prof Castles has blogged on the Read Oxford website, the list was devised locally, it’s endorsed by the University where I did my Masters in Applied Linguistics, and is widely used in my local schools. Here are some of the first 50 words on the standard list:

They contain common and uncommon spellings, they’re short and they’re long, some are built with suffixes and some aren’t. Such lists don’t help children learn spelling patterns.

The Oxford Wordlist was developed by researching the most common words in children’s writing and reading development in Australia in 2007. Its stated purpose is to allow educators to create “customised wordlists for early writers, use these lists to plan relevant programs, and determine those words most likely to allow all students to engage in the curriculum”.

High-frequency word lists are often used as spelling lists

The main thing I’ve seen the Oxford Wordlist used for in schools is to create spelling lists. A section of the list is assigned as the week’s spelling words, with a test at the end of the week. Teaching approaches tend to err on the side of the highly visual – flashcards, look-cover-write-check etc, plus reciting mnemonics (those dratted Big Elephants!) and letter names, rather than learning about linguistic properties and patterns in the words. I’d love to reorganise these lists in ways that would make clearer, more useful points about spelling.

Absolute beginners are encouraged to memorise the first few words from high-frequency word lists – which on the Oxford Wordlist means “I”, “a”, “the”, “and”, “he”, “was”, “to”, “my”, “it”, “in”, “is” – often before they have been taught all the relevant letters, and while many still have only a shaky grasp of the alphabetic principle. Parents are not, in my experience, instructed to focus on pronunciation and letters and letter sequences, rather than shape or visual features. Sometimes, quite the reverse.

Repetition? Sure. Some children try to rote-learn the same 100 high-frequency words without success for years on end.

I think teachers only ask children to rote-memorise words that are highly decodable even for beginners (like “on” and “in”) because they are not taught how to provide explicit, systematic phonics instruction, so they don’t know any better. Last week, I asked a group of about 60 Canberra teachers who had been taught about the sounds of spoken English at university. Not one hand went up. If I’d paid thousands for a degree that didn’t teach me something so fundamental to success and satisfaction in my future career, I’d be thinking about asking for my money back.

Good explicit phonics programs already contain sight words

I don’t understand why sight word lists even exist as separate Things from the explicit, systematic phonics programs in which sight word teaching is best embedded.

How can you know which words a child can’t sound out yet without knowing which sound-spelling correspondences have been taught so far?

Most explicit, systematic phonics programs nominate a few words in their little books at each level which contain harder spellings than those taught so far. These are to be learnt as wholes before reading, or children are to be assisted when they get to these words. It’s pretty hard to make an interesting story up using a very restricted set of spellings, so that’s understandable.

These words depend on the teaching sequence and stage. The “(learn by) heart words” in Little Learners Love Literacy Stage 3 (at which point children have been taught the most common sounds for the letters m, s, f, a, p, t, c, i, b, h, n, o, d, g, l, v, y, r, e, qu and z) are “the”, “he”, “was” and “she”.

The words “readers may need help with” in one of the Sounds~Write Unit 3 books (having been taught the main sounds for the letters a, i, m, s, t, n, p, o, b, c, g and h) are “said”, “did”, “and”, “the”, “of”, “put”, “but”, “is”, “a” and “Mum”.

These are both good explicit, systematic phonics programs, and both already include precisely what Prof Castles calls “sight words”.

There is no need for a separate “sight words” list.

Better terminology and methodology

The most recent contributions to the DDOLL discussion on this topic seem to be coming to the conclusion that it’s time we stopped using the term “sight words”. Hooray to that I say. It means too many different things to too many different people, and it gives the impression that reading involves visual memorisation of words, not something much more complex and linguistic.

I’d love everyone to give up on the thankless task of separating regular and irregular words, in order to teach them in two different ways. We just need to do better word study, so that we understand and teach about the many layers in our words: sounds (phonology), spelling (orthography), meaningful parts (morphology), function in sentences (syntax) and meaning or meanings (semantics).

The fuller and richer one’s knowledge of all these things, the more easily a word is recalled (Brief ad segue: the international expert on all this stuff, Prof Maryanne Wolf, will be speaking in Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne in early September, you should come).

Even etymology is sometimes useful in word study, e.g. the apparently random letter O in the word “people” links it to the Latin word “populus” from whence also comes “population”, “popular”, “populous”, “vox pop” etc. Plus, Romans, Vikings and others with swords and funny hats can help make all sorts of stuff, including word study, more interesting to kids.

I really do enjoy reading what you write. I am a teacher who is trying to learn more about the benefits of phonics however I get frustrated at words like ‘are’ ‘said’ etc because I don’t know how you sound them out then resort to learning by sight and memory. Please help

Hi Sarah, yes, it’s pretty annoying that a lot of common words contain an unusual spelling or two. However the rest of these words are generally pretty regular – the only irregular things about words like “straight” and “friend” are the vowel sounds’ spellings. All four consonants in both words are spelt utterly regularly. The word “are” just has an extra letter E on the end of a very normal way to spell “ar” as in “car”, “farm”, “dark” and “chart”. The word “said” begins and ends with regular consonant spellings, and probably in the olden days was pronounced to rhyme with “paid” and “laid” and “played”. In fact old Bibles contain things like, “he had compassion on her, and sayed unto her, wepe not”, but sadly pronunciation changes over time and now we rhyme “said” with “red”. I find that kids don’t get too phased by funny spellings once they know English is a mixture of several old languages that have changed over time, and they have a sense that adults are knowledgeable about the system and able to help them learn it a bit at a time. Hope that helps!

The blogpost makes several cogent points. e.g.

There is no need for a separate “sight words”list

I’d love everyone to give up on the thankless task of separating regular and irregular words, in order to teach them in two different ways.

How can you know which words a child can’t sound out yet without knowing which sound-spelling correspondences have been taught so far?

teachers only ask children to rote-memorise words that are highly decodable even for beginners (like “on” and “in”) because they are not taught how to provide explicit, systematic phonics instruction, so they don’t know any better.

The thing is, the EdLand landscape is littered with such detritus. It infests not only the classroom environment, but the research environment as well. When terminological detritus is coupled with the “childrens’ books” detritus of the “whole language” dominated era (which has morphed into the present “balanced literacy/mixed methods” era), the wonder is that children cope with reading instruction as successfully as they do.

What’s the antidote? We have to live with the EdLand we have rather than what we wish it was. I’d say the way forward is to promote use of the Alphabetic Code Screening Check technology that has been adventitiously constructed and implemented in England as part of the “Synthetic Phonics” initiative. My understanding is that steps are now underway to apply the technology in Australia. If so, that will be an important step forward.

Well sayed Alison

The DDOLL discussion has been frustrating. But partly, I think, because research hasn’t caught up with modern practice.

(I think that said, paid & laid were originally two syllable words; say/ed, pay/ed & lay/ed. )

Thanks, Maggie. Yes, the regular v irregular word distinction really flummoxes me, there are 5 phonemes in “friend” four of which are spelt completely regularly, so how does that make the entire word irregular? How interesting that “sayed” had 2 syllables, just as “jumped” and “called” seem to for many speakers of Indian English, perhaps over-generalising from “batted” and “padded”. Maybe the Indian English version of this morpheme will ultimately triumph again!!

After reading your post about sight words, I reorganized most of the Dolch sight words into patterns . I used the short vowel and open syllable word patterns for my struggling readers. I liked the word “cognitive load” when describing early levelled books as well. Makes sense to me.

Parents also liked the reorganization of the sight words as well.

You are exactly right about exception/irregular words and the best ways of teaching them. Keep up the good work. Many academics and even teachers advocate teaching them as sight words because they don’t know any other methods and can’t imagine that there might be any alternative methods. They need to learn from people like you, John Bald and I who have more effective and sophisticated ways of teaching the irregularity of the English language.

I believe that a large part of the problem with academics fascination with teaching irregular words as sight words is the dual route cascaded model of reading. This model is a description of how words are read, but has in fact been turned into a prescription for how reading should be taught. Words are read via the sub-lexical route by sounding out. This suggests that in order for a particular word to be able to be sounded out that the word a) has to be phonetic (or close to it); and the reader needs to b) know the letter-sound relationships in the word and c) be able to blend them together to get the correct pronunciation. Therefore synthetic phonics is compatible with and can be the prescription for skilled reading via the sub-lexical route. However, all is not so straightforward with the lexical route. Looking at the lexical route superficially can lead one to potentially inaccurate prescriptions for how to read irregularly spelt and even other sorts of words. Words that are committed to long term memory (the lexicon) are read automatically as ‘wholes’ via the lexical route. The dual route cascade model has little to say about how words made their way into long term memory. It also has little to say about how the visual form of words and their pronunciations are encoded i.e. in what form they are stored in memory. The reason for this is that the theory is a simple description of the process of single word reading only. The dual route describes words as being read automatically and as wholes on the lexical route. Does this mean that they were learnt as wholes or should be taught as wholes? No. Even the phonetic words that were originally read via the sub-lexical route make their way into the lexicon and are then read automatically via the lexical route. In the same way, who can say that irregular words a) can’t be read without assistance of the sub-lexical route and/or b) have to be taught as a whole ‘sight’ word. Unfortunately, this is what most academics and teachers are saying.

Karina, have you read the original post? What you describe above is precisely not what was said. In that post I go to some length to distinguish between the process of reading by sight (or the lexical route if you use the dual route terminology) and the practice of teaching “sight words”. The exact question raised is *how* do children come to read by sight – what is the learning process? So the whole point is to distinguish the reading process represented in something like the dual route model from how it might be taught. And it is explicitly stated that the evidence suggests that phonological decoding (i.e. reading by the sub-lexical route) is a key part of learning to read by sight, for all words – that’s the self-teaching hypothesis). The question then raised is whether other teaching methods, such as an intensive focus on the spellings of a small number of individual high-frequency words, may also be effective to supplement this. So I don’t think what you describe above is what most academics are saying at all, at least the ones I know! Given the complexities in this area, and the misunderstandings that can arise, I think it is important that we all do our best to represent the ideas of others accurately.

You have a point. You are quite right and I apologise. I didn’t read through the original posting, only Alison’s posting here on Spelfabet. This is because I am aware of research that you have done and/or support which concludes the teaching of irregular words by sight is effective. As I opened the original posting, again a repetition of your research suggesting teaching sight words is effective is repeated. But how effective is it? The ‘Look Say’ method is more effective at teaching reading (both regular and exception words) than not teaching reading at all. However, it has been established as being the worst method of teaching reading when compared to all other possible methods of instruction. If teaching exception words as sight words (which is the look-say method) is compared to not teaching them at all and/or includes no comparison to alternative methods, then how useful are the results and conclusions from this type of research? All we can conclude is that teaching sight words is about as effective as look-say, which isn’t a great recommendation.

There are other methods of teaching exception words than the limited suggestions of: writing, copying, repeated pronunciation, or sequential letter naming. All of these suggestions are whole word/whole language methods (i.e. lexical route methods) only. This limited list screams the belief that there is no place whatsoever for pointing out letter-sound correspondences in the teaching of exception words.

When research was done to compare reading instruction methods: look-Say, multi-cueing, analytic phonics and synthetic phonics, the higher the phonics content, the more effective the method was found to be. This analysis should, in my opinion also be extended to the teaching of exception words on their own. The higher the phonics content in the teaching of it, the more effective the teaching. Exception words don’t have all regular one-to-one letter-sound correspondences. This would seem to rule out the sub-lexical route (synthetic phonics) for reading these words – OR DOES IT?

Researchers Johnstone and Watson do not recommend teaching any words by sight. They suggest that when teaching exception words that both regular and irregular grapheme-phoneme correspondences are pointed out. It seems that with Johnstone and Watson’s advice, many exception words can be read via the sub-lexical route by teaching word-specific grapheme-phoneme correspondences. Many exception words only have one letter that does not follow the regular pattern. Wouldn’t it be more effective to teach that letter-sound correspondence (which can be generalised to several other exception words) than defaulting to teaching the whole word as irregular? Especially since patterns exist in the irregularity of English.

In the word ‘want’ only one letter doesn’t follow regular letter-sound correspondences – the a, which takes an /o/ sound. However, this is not the only word where a makes the sound /o/. In most words that begin with wa and swa, the a takes the /o/ sound. By looking for patterns of irregularity and teaching words in groups that have the same pattern, e.g. want, was, watch, waddle, swap, swan, swab etc. we can make the process more efficient than teaching exception words on a word by word basis in isolation. There are many groups that share the same irregular grapheme that can be taught together e.g. would, should & could & bye, dye, rye, eye.

Some techniques from analytic phonics can also be used to teach exception words. These include analysis of onset-rime. Many groups of exception words contain a regular onset and a common irregular rime e.g. some & come; all, ball, call, tall, wall, stall, small etc.

An added ingredient that is missing from reading instruction and would help with the learning of exception words is the colourful history of English word origin and irregularity. Context is important in the learning of new concepts in all academic subjects, but is often ignored when teaching reading and spelling. When the teacher has a good knowledge of the history of the English language, this can be used to great effect with anchoring words and their spelling into long-term memory and their recall from memory. For instance, when I teach ‘kn’ as in knife, knight, knit etc. I tell the story of how those words came from Scandanavia and were brought to England by the vikings. I explain the k used to be pronounced and that words in Scandanvian languages that have this spelling still pronounce the k. The children are told that in English we stopped pronouncing the k, but left the spelling the same as in the olden days. I let the kids have fun by pronouncing all the words with this grapheme like vikings and recommend using this pronunciation when trying to recall its spelling. Similarly, I tell the children that the grapheme ‘igh’ now makes the long i sound (as in island), but used to make a different kind of gutteral sound (which I demonstrate for them and by so doing disgust them at the same time). In the middle ages English was more Germanic sounding than now. Children have fun pronouncing words in the old way and this becomes a memory hook for learning and recalling words with this spelling if the long ī sound.

The irregular words which begin with wa and swa mostly had their origins from Germanic languages where the w was pronounced as /v/. When the /v/ sound changed to /w/, the a evolved to an /o/ sound as well. Even the irregular spelling of ‘yacht’ can be explained in the form of a story. When the first English dictionary was to be printed, it was sent to Holland for printing. This was the closest country with the printing press at the time. On the way over, the handwritten version of the dictionary contained the spelling ‘yott’. The dutch, who did not understand the English language very well, confused the ‘ach’ in Scottish words e.g. Lachlan with the /o/ in English words and inserted ‘ach’ instead of o into yacht and that is how we got stuck with that silly spelling. We also had additional letters in the English language, including eth and thorn (voiced and unvoiced th). As these letters were not included in the dutch language nor printing press, they had to be replaced by the digraph ‘th’. The stories of English irregularity are fascinating to adults and children alike and should not be underestimated as a teaching tool.

Although spelling reform in the history of English found it difficult to achieve one-to-one correspondence, efforts were made to make it more obvious as to whether vowels were to be pronounced with the short sound (a apple, e, egg) or the long sound (a alien, e, evil). Knowledge of open and closed syllables is helpful for an understanding of how to arrive at the correct pronunciation. For instance, if you understand that open syllables end in a long vowel, then words and prefixes such as: he, she, we, me, be, so, no, go, co- no(tice), I, bi-, tri-, a(lien), ta(ble), u(nicorn) etc. are much more easily read and are therefore not exception words.

In conclusion, the teaching of exception words can be a lot more sophisticated, efficient and interesting (and I hypothesise that research on comparative methods of teaching them would also establish as more effective) than the blunt instrument of teaching each irregular word on it’s own, out of context, as a whole and with no reference to phonics whatsoever.

For academics and teachers with little knowledge of the history of the English language and how to teach it effectively, I recommend books: ‘The Stories of English’ and ‘Spell it Out’ by David Crystal, the video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oNkiatQo-pQ by Alison Clarke of Spelfabet and the publications and blog posts of John Bald https://books.google.com.au/books/about/Using_Phonics_to_Teach_Reading_Spelling.html?id=RYB1P7UAGosC.

For those teaching children with Surface Dyslexia, they might want to use (in addition to the methods of teaching exception words explained above) the multi-sensory techniques of Grace Fernald.

Kind regards.

Karina

Wow Karina, you have a very extensive knowledge of our spelling system, your students are very lucky. Alison C

Dear Karina,

Thanks for your comments (and I agree with Alison about your extensive knowledge of the origins of the spelling system), but I think a lot of what you say here works on an either/or assumption about phonics and sight word training that is not what is proposed in the original post. You say “there is no place whatsoever for pointing out letter-sound correspondences in the teaching of exception words”, but that is not what is suggested at all. In contrast, the benefit of this knowledge is taken as a given and is discussed at the outset in the context of the self-teaching hypothesis. This hypothesis proposes precisely that, at the individual word level and for both regular and irregular words, children benefit from decoding the words, and identifying clusters of letters that relate to individual sounds – this is a key means by which they come to recognise words “by sight”. I and my colleagues have examined whether this benefit also applies to irregular words and found this to be the case (although the benefit for regular words is stronger – see e.g. Wang et al, 2012).

So this method of teaching words is not in contention. The question asked in the post is whether, *in addition* to this, there are other word-level methods that may assist a child further. And evidence is then presented that the answer is yes, and that these methods do not interfere with the letter-sound based learning. You say that there is no evidence presented that involves a comparison with other methods but that is not the case: the Shapiro and Solity paper referred to directly compared different teaching methods which had a greater or lesser emphasis on sight words (and correspondingly a greater or lesser emphasis on teaching multiple letter-sound correspondences).

Many of the methods for teaching individual words that you describe above may well be effective – I think, in particular, that focussing children on the morphology of words is something that is likely to be very important, and deserves much more research attention. We just need the evidence. In the meantime, I have restricted my list of the the methods that can be effective (in addition to phonological decoding) to the ones that have been used successfully in published studies. As a reading researcher, that is my job – though I fully agree with you that there is much more comparative research on the effectiveness of specific methods that needs to be done.

Modifying or ‘tweaking’ the pronunciation of a word after it has been sounded out and blended is a routine state of affairs with synthetic phonics.

Thus, a word like ‘said’ is easy. Just sound it out /s/ /ai/ /d/ – leading to ‘sayed’ – and then modify the pronunciation to ‘sed’. This is also required to address different accents for various words, “In our region, we pronounce that word like this…..”

Another way to approach words with such spellings is through the spelling route: “In this word [said], the letters here [ai] are code for the sound /e/. Another word like this is the word ‘again’ and a further word with this spelling pattern is ‘against’.”

You can teach any spelling alternative at all, no matter how unusual, in this way:

http://www.phonicsinternational.com/FR_PI_straight.pdf

Alison, you know your posts are always great – I’ve added this one to the forum at the International Foundation for Effective Reading Instruction – featuring Professor Anne Castles’ guest-blog posting on sight words! See here:

http://www.iferi.org/iferi_forum/viewtopic.php?f=2&t=610&p=1040#p1040

Dear Alison,

Thanks very much for this thoughtful post (and for the planet brain comment – you’re way too kind!). I have linked to it in a comment on the ReadOxford blog, and you might also be interested to see responses on there from Laura Shapiro and Jonathan Solity. I also made the following suggestion, that I will repost here as might be of interest to your readers:

“Looking at the comments, it seems to me that the basis of much of the confusion is around the term “sight words” and what they mean, as Alison Clarke has pointed out in her response on her blog (which I recommend you read: http://www.spelfabet.com.au/2016/07/dissing-choosing-and-teaching-sight-words/). I wonder if a helpful way of dealing with the definitional problem is to move away from the term “sight words” and instead just make a distinction between “rule-focus” and “word-focus” in reading instruction. We know that children need to be explicitly taught the correspondences between letters and sounds in English as part of a structured program. Broadly speaking, when we are teaching those correspondences, we are taking a “rule-focus” (even though the teaching may involve words, and so children may simultaneously be learning to recognise the spellings of those words as they are learning the rules). We also know that some words do not follow those typical rules and that, if they are ones that children are likely to see regularly, they need some special attention. So when we teach these words, we take a “word-focus” (even though, again, a child may still be learning rules as part of this teaching, as not all of the grapheme-correspondences in the word will be irregular).

If we were clearer on a terminology something along these lines, we could then move to addressing the outstanding questions of how best to conduct “word-focussed” instruction, when it should be introduced, and for how many words etc.”

Hi Anne, Thanks for getting this discussion happening, it is really useful and interesting. I’m not sure about the term “rules” either, as these are meant to work consistently and spelling rules never do, plus I read some spelling rules aloud to the workshops I presented in Burnie and Canberra recently – one was mainly for Speech Pathologists and the other teachers – and nobody could tell me what they meant, it’s only when you see a corpus of words that demonstrate the rule that it makes sense. E.g. Fly-flies, try-tried etc plus baby-babies, lolly-lollies, but tie-ties-tying, die-died-dying, fly-flying or try-tryhard, and then tray-trays, donkey-donkeys, boy-boys. Extensive examples and lots of practice, rather than trying to learn rules couched in complex language is what’s needed, I think, both for learners and for teachers. Also, I can’t think of any words where knowledge of phoneme-grapheme correspondences aren’t helpful in word recognition (not just the 64 you need to get your reading wheels turning, but the 160 or so that occur in at least a dozen words I’d guess most adults know) and to spell well you need a lot more than just 64. I’m not sure the self-teaching hypothesis is enough after that. I see kids all the time who’ve done Multilit so they can read reasonably competently (except for the middles of long, unfamiliar words) but they still can’t spell because they haven’t really pulled the words they know apart in patterned groups and had a good look and listen to their entrails, then put them back together again. This is what interests me most, I think we skim along imagining spelling doesn’t matter very much but to use language at a high level you need to know the difference between discreet and discrete, principal and principle etc. My sister taught law students at the ANU for years and even these supposedly best-and-brightest students often can’t spell or put a sentence together very well. Which kind of matters for clear and precise communication in our litigious society.

I am enjoying this thoughtful (and much needed) discussion.

Rather than a “rule-focus” versus “word-focus” approach I would advocate an inquiry approach for words that seem to be phonological or orthographic “rule breakers”. There’s a reason why every word is spelled as it is, and giving the student the reason is a powerful learning tool!

Take, for example, the “sight word” (aka high frequency, aka “irregular” word) . The word matrix for on the page linked here explains why is spelled as it is. And the history of the word explains it pronunciation. http://support.lexercise.com/entries/20535696-Word-Inquiry-It-s-a-Structured-Language-Approach

We teach this to students and parents using technology to make it lively. Using the technology (micro0-video lessons) , teachers could easily teach it, too.

Absolutely agree: “We just need to do better word study.”

This means that teachers and reading specialists have to have expertise in word structure –and as your experience with the Canberra teachers, we are not making much progress on that front! In general, SLPs don’t have deep knowledge about written word structure either. (See: http://www.asha.org/events/convention/handouts/2008/1966_barrie-blackley_sandie_2/ )

After decades of very little progress in terms of university preparation for teachers of reading we decided to take reading science directly to parents of struggling readers via teletherapy. In our digital age there are many ways to learn and many ways to support learning.

Thanks for your work!

I agree, I learnt much more about syntax and punctuation from working as an editor, doing the Cambridge RSA course, and teaching adult ESL learners, than I learnt in my undergrad degree. I learnt virtually nothing about any of these topics in my Masters, it was all about philosophy and sociology of language, and very infected by the Educational fashion for making stuff up without reference to any sort of proper evidence. I agree that the task of re-educating an entire teaching workforce quickly is not going to be accomplished entirely face to face, it will require a lot of technology, with 10 and 15 and 20-minute youtube videos, probably. Teachers are very distracted and time-poor. Thanks for the nice feedback! Alison

I need to freedownload your website please send me the link

Thanks and regards

Janavani

You can download any of the free resources in my shop via the shopping cart, just click on the $0 items and then the total will be $0 and you’ll bypass the payment process and go straight to downloads

Wow Alison, all these exchanges and discussion on how to teach reading can either be ‘enlightening’ or ‘confusing’. Coming from the Philippines, I learned English simultaneously with Filipino and Chinese curriculum in the 70’s. Trying to recall how we were taught then, I can distinctly remember that the emphasis was on looking for spelling patterns within the irregular words. In so doing, one can transfer that to new words encountered. I am not a “teacher” of Reading as my undergrad studies (in my 40’s) was B Ed in Early Childhood. Now I am in my sixth year in teaching Prep, I do find sight words ‘memorising’ to be double-edged sword wherein the competent learner can breeze through the text upon seeing the word without having to decode and yet a struggling reader will find it hard enough to decode words with clear onset and rimes let alone recall irregular words such as sight words. Still, our whole school approach is to teach ‘sight words’ by rote and word study comes late in the Year 1 level. I tend to lean towards full phonological awareness in my word approach. Alison, have you encountered the Reading Horizons Reading Program (American, and am not in any way endorsing it commercially) which may initially be rule focused which I used for some ‘struggling’ readers and had some noticeable improvement. At any rate, it’s good to read about all this as I am very interested on how i can help make it easier for my students to learn to read.

Hi Caroline, yes, there seem to be a bunch of kids who will learn to read fairly easily no matter what method is used, but others who need the teacher to “crack” the spelling code for them, systematically and explicitly, or they simply can’t learn it. I haven’t seen the Reading Horizons program but I am looking it up now, always interested to hear of programs which have a solid focus on phonemic awareness and spelling pattern knowledge as well as the comprehension, fluency and vocabulary we all agree are important.

I am a parent of a Prep and Year 1 child who thinks the way sight words are taught is absolutely ridiculous. I asked the teacher for the sight words that my children would be learning throughout the year and put them into lists that either followed the same syllable rule or had the same sound. eg in. is, it, go, no, dad, had. My kids breezed through sight words once I did this. Why aren’t teachers knowledgeable in this simple procedure???

Yes, I must put a reorganised list of Oxford Words on my website, as that seems to be the HF word list of choice in my local schools. Someone sent me the link to just such a list but I have misplaced it, sigh.

Hi Alison, I am a SP supporting a child with a severe physical disability who is non verbal. I am interested about how I might incorporate multi-sensory teaching principles for her for literacy. She can do limited hand over hand movement.

This is what I would try, Janice Light is excellent: http://aacliteracy.psu.edu/index.php/page/show/id/15/index.html

Thank you, this is fantastic!

I like to teach understanding of the sight words so my kids can become super readers!

WHY have so many teachers, experts, academics, etc. complicated learning to read and spell, what is essentially a pretty simple language. Sight words become sight words permanently because of the number of times we see or write them in context (start with simple sentences), not by learning them as “tricky” words, because they don’t

have to be. Lists of “sight words” should be broken up into easily understood and learned patterns.I have been teaching this way for over 40 years, both in and out of classrooms and can prove its effectiveness to any one

at any relevant age. Show me your worst readers and.spellers and I will turn them around as a challenge.

Hi Brian, I agree, the whole idea that tricky words have to be memorised visually is not consistent with the reading science, they need to be broken up and taught in a patterned way like other words. Good on you for your effective work and let’s hope that more and more people can start teaching this way too. Alison

When implementing effective reading instruction, only a small set of words need be taught as sight words. Reading most words should be an effortless act. Reading Racetrack Sight Word Activity Teach sight word recognition using this exercise that involves multiple rounds of instruction and practice.