Renaming letters

0 Replies

Letter names have recently been the topic of discussion on a US email list I subscribe to, and today someone reframed the discussion in an interesting way.

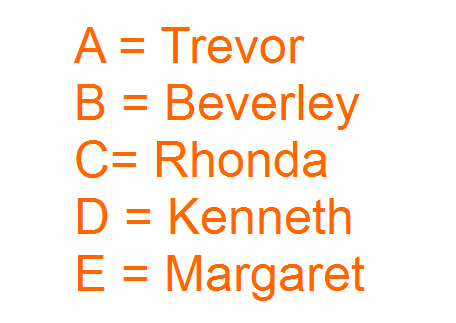

US Psychologist Steve Dykstra pointed out that if we renamed all the letters of the alphabet – for example, if we decided to call the letter A not "ay" but "Mary", the letter B "Fred" and the letter C "Juanita", and so on – it would make absolutely no difference to whether we could read.

That is, we would still be able to use the letters.

We just wouldn't be able to talk about them. For that, you need to know the names.

However, if we changed the way letters represent sounds, e.g. swapped the sounds represented by A and B, C and D, and so on, we'd be lost, and unable to read, unless we put in a lot of time and effort relearning all the new letter-sound relationships.

However, if we changed the way letters represent sounds, e.g. swapped the sounds represented by A and B, C and D, and so on, we'd be lost, and unable to read, unless we put in a lot of time and effort relearning all the new letter-sound relationships.

"Predicts" doesn't mean "is a prerequisite"

Letter naming is a good predictor of later reading skill, and this is often interpreted to mean that it's a critical prerequisite for reading.

This is a bit like saying that shoe size is a good predictor of future height, so if we want children to be taller, we should do things to make their feet bigger.

Letter recognition is undoubtedly a critical prerequisite for reading, otherwise our alphabet would mean about as much to us in ordinary letters as it does in Wingdings.

However, letter recognition shouldn't be confused with letter naming. You have to be able to recognise letters to name them, but the reverse does not apply. I can recognise a shape with five straight, equal sides, and put it in the right hole in a shapesorter, without knowing it's called a pentagon.

Sounds first, letter names later

Our initial focus in early reading/spelling teaching should be on helping children recognise letters, discriminate and manipulate sounds in spoken words and learn which letters/spellings represent which sounds.

Later on, when they can read little words with simple spellings, they'll need to learn that:

- the same sound can be represented by a number of spellings (e.g. the "a" sound in "plait", "timbre" and "salmon"), and

- there are multiple sounds for each letter (e.g. the letter "a" in "can", "blast", "want" and "all"), and for many spellings of more than one letter (e.g the "ou" in "out", "soup", "touch", "soul" and "jealous").

To teach this to a whole class, it can be useful to have a name for each letter symbol. And of course in later life it's sometimes necessary to spell a word out using letter names, but unless you work somewhere like a call centre, you probably don't have to do it very often.

As a major early literacy goal, consuming lots of time and energy which could otherwise be spent on teaching children how to use letters, letter naming doesn't really cut it.

Leave a Reply