Balanced literacy

22 Replies

Ask schools how they teach reading and spelling to beginners, and you’re likely to be told they take a “balanced literacy” approach, combining the best of all approaches.

This sounds eminently sensible, but what does it mean in practice?

As we are about to start the school year here in Australia, let’s think about this question from a learners’ perspective.

Experience balanced literacy

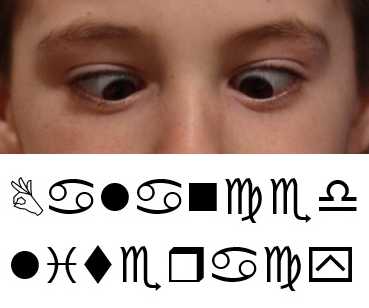

Imagine you’re a five-year-old starting school, and you’re a true reading/writing beginner. Your parents/grandparents/kinder teachers have not already taught you how to read or write. You can’t recognise any letters or words, and you don’t know that words are made of sounds and letters are how we represent these sounds.

To you, the alphabet might as well be Wingdings, so that the sentence “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog” would look like this:

High-frequency words

In a “balanced literacy” school, teachers are very likely to firstly present you with a list of high-frequency words, for example starting with the “Golden words”: “a”, “and”, “be”, “I”, “in”, “is”, “it”, “of”, “that”, “the”, “to” and “was”.

Your job is to memorise these words, which to you look like this:

These 12 words in ordinary letters mean that the very first thing you learn about literacy at school is that when you see the letter A, say “u”.

You might notice that the sound “u” is also in the word “the”, except that in “the” it’s written with a letter E, not a letter A.

You might also notice that the letter A, which you just learnt to say “u” to, sounds different in the words “and” and “that”, and different again in the word “was”.

The sound “z” in “is” and “was” is written with a letter S, and the sound “v” in “of” is written with a letter F.

Just 12 little words, but already you’re being presented with a whole lot of spelling complexity that nobody unpacks for you. You’re just told to swallow it whole.

Initial Phonics

As well as high-frequency words, beginners are usually taught the alphabet, which has 26 letters, each of which (beginners are told) “says” a single sound.

There are friezes around the classroom with pictures and words on them showing the alphabet and giving example words. The text on these friezes looks like this:

Your class works through the letters one at a time, studying groups of words starting with each letter.

For example, you learn that the letter A has two forms, uppercase “A” and lowercase “a”, and that it is at the beginning of words such as “apple”, “arm”, “apron”, “alarm”, “aeroplane”, “Australia” and “always”. If you’re observant, you might also notice a storybook by “Aesop”, and a sign saying “aikido”. To you, these words look like:

Your teacher says that the letter A/a is called “ay” and makes the sound “a” as in “apple”.

Your teacher says that the letter A/a is called “ay” and makes the sound “a” as in “apple”.

This makes sense for words like “apple”, “ant” and “astronaut”.

However, to your ears (and everyone else’s), the first sound in “arm” is “ar”, not “a” as in “apple” at all. The first sound in “apron” sounds like “ay”, and the first sound in “alarm” sounds like “uh”.

The first sounds in “aeroplane”, “Australia”, “always”, “Aesop” and “aikido” are “air”, “o”, “or”, “ee” and “I”. There is no “a” as in “apple in any of these words.

So either there is something wrong with your ears, or your teacher is only telling you part of the story about what the letter “A” represents. Or perhaps the relationship between sounds and letters is even more random than you thought.

Letters also appear in the middles and at the ends of words, but you don’t usually study them in these locations. You’re taught to mainly focus on pictures and first letters.

The only typically syllable-final spelling you’re likely to study while learning the alphabet is the letter X, but your first-sound-fixated classroom frieze probably says “X is for xylophone”, or possibly “X is for X-Ray”. This helps you deduce that the letter X represents the sound “z” (true, but rare, at syllable beginnings – think Xerox, xylem and Xena the Warrior Princess), or the sound “e” as in “egg”.

Names

You and your classmates’ names include all the most popular baby names of 2009, so you’re also being encouraged to read and write:

The difference between what the teacher is telling you about the spellings “ch”, “i”, “y” and “th” and:

- the “ch” in “Chloe”, “Charlotte” and “Lachlan”,

- the “i” in “Olivia”, “Mia”, “Sienna”, “Amelia” and “William”,

- the “y” in “Emily” and “Riley” and the

- “th” in “Thomas”

might finally convince you to give up trying to work out how sounds and letters are related, and just try to memorise words as wholes.

Reading Real Books

Your class is also listening to your teacher read books, and you are being encouraged to attempt to read them yourself. You are allowed to choose your own books in the library, so you look for ones with good pictures and not too many Wingdings. In class you’re trying to read books which are considered Level 1 books, for absolute beginners.

The text in these books is often quite repetitive, and these books usually have lots of helpful pictures, so you get in the habit of “reading” them by looking at the pictures, looking at first letters, and guessing.

This is encouraged by your teacher.

Incidental Phonics

Sometimes the teacher points out a letter you have been studying while reading a Big Book to the class. For example when you’re studying the letter “c” you might notice “cat”, “duck”, “chicken”, “bicycle”, “science”, “ocean”, “cello”, “moustache”, “special” and “ciao”. From these words you might, if you’re very smart, deduce that the letter “c” has something to do with representing the sounds “k”, “ch”, “s” and “sh”, but since you don’t get to study these patterns in decent samples of words, one by one, you can’t figure out how any of them work.

Writing

When it’s time to write, you first do some tracing letters and copying, so that you know what their shapes are. You form some letters in an inefficient way that will make it harder for you to write quickly later on, starting at the bottom instead of the top, and going round the wrong way. You may or may not be given corrective feedback.

After that, you pretty much graduate directly to being given a blank page and encouraged to put your name on it, draw a picture and then write a few words about the picture.

You can write any words you like. The only problem is that you don’t know how to spell them, so you try to stick to words you’ve memorised, or ask the teacher to tell you how to spell them, or copy something from the dozens of words on the classroom wall, or just try your best to sound out a word. This gives you many opportunities to practise spelling mistakes.

Spelling

You practise spelling high-frequency words, but you do them in order from most to least frequent, rather than learning words with shared spelling patterns together. This makes it hard to identify and learn the patterns.

Sometimes your spelling words might be related to a classroom theme, for example if you’re studying tadpoles, your spelling list might include the following words: frog, water, pond, tank, swim, tadpole, tail, legs, eggs, jump. Again, these words contain a mixture of spelling patterns so it’s hard to learn anything useful about spelling by studying them as a group.

“Balanced literacy” means “literacy chaos”

I hope by now you agree with me that from the learner’s perspective, “balanced literacy” could more accurately be called “literacy chaos”.

It’s not balanced, it’s just a mess. The logic underpinning it is unclear, and it has no proper sequence. It contains inaccuracies, contradictions and many gaps e.g. middle and ending sounds/spellings, blending, segmenting and handwriting.

It’s a small miracle, and a tribute to the hard work and lateral thinking of many early years teachers, that only about 20% of children still can’t really read or spell after a year of “balanced literacy” instruction. I suspect that lots of kids are also being given the low-down outside school – all those parents and grandmas and grandpas with their alphabet fridge magnets and Dr Seuss books, bless them.

Teachers deserve to be given a more coherent, evidence-based and effective system to teach early literacy, either at university or inservice training, not least for their own job satisfaction.

In my experience, teachers really hate getting to the end of the year and still having some students in their class who can’t read or spell.

Synthetic Phonics

Little children should initially be taught just a small number of sounds and their letters, and then practice these until they can both read and spell little words containing them, without being distracted and confused by other sounds/letters and more complicated spellings.

Then more sounds and spellings should be added in a gradual, explicit, systematic way, till children have mastered reading and spelling words containing all the main patterns of our language. There are 44 sounds in spoken English and each has more than one spelling, made up of 1, 2, 3 or 4 letters. Many spellings are shared by more than one sound. It’s complicated, but teachable and learnable.

This sort of explicit, systematic, sounds-and-letters early literacy teaching is called Synthetic Phonics, and the sooner it replaces “Balanced Literacy” in early years classrooms, the happier I will be, and the more children will successfully learn to read and spell in their first year of school.

P.S. Synthetic Phonics does not mean children missing out on quality children’s literature. Until kids can read this literature themselves, adults should read it to them.

P.S.2 on 19/3/16: I’ve just discovered a great article by the Thomas B Fordham Foundation which explains in much more detail what’s wrong with “balanced literacy”. It’s called Whole Language Lives On: The Illusion of Balanced Reading Instruction.

[…] Read another good article from the spelfabet blog about the confused notion of ‘balanced literacy’ http://www.spelfabet.com.au/2014/01/balanced-literacy/ […]

Thanks Alison for your awesome blog, I'm sure it'll change lives.

I'm a mum, I'm a believer (in synthetic phonics) and I'm frustrated. I've had to choose from almost 10 schools, none of which teach using explicit synthetic phonics and the one I've chosen is full of good, educated people. However If I walk in trying to convince them to change from "a balanced approach" to synthetic phonics because my favourite blog says so I can only imagine the tea room talk about me (and the effect on my kids).

Where can we start change? Are the teaching methods decided at a state level (Vic) or district or Principle? Who do we need to talk to? How do we talk to them? Do we need to fundraise for more teacher education and invite your convincing self to plead our case?

Hi Meegan, thanks again for your encouraging words, I struggle with this stuff too, and I really don’t want to join in any of the teacher-bashing that phonics advocates sometimes get into, I think teachers are dedicated people with many skills that I don’t have, but they don’t know much about our sounds-and-spellings system, and they need to.

At least here in Victoria, schools seem to have a lot of control over teaching methods at present, so the Principal’s support is critical, but I just tend to latch onto anyone who shows an interest. Often that’s parents and/or the special needs/integration staff who are having to deal most closely with learners for whom the current classroom-based teaching hasn’t worked. Once those kids start reading and writing, their class teachers often start asking me to have a look at the other strugglers in their class. That gives me an opening to report back to them on what I found and what I plan to do, and offer them Synthetic Phonics activities to use with these students. Often teachers then start using these activities with the whole class, so then I have to make/buy new activities to use in my groups, because the kids complain “we’ve done this in class”, which is more work for me but I couldn’t be happier about it.

Once teachers start to “get” and try synthetic phonics, it gives them a logical, sequential framework for their early literacy teaching instead of a mishmash, and they say “wow, this really works and makes so much sense, why didn’t anyone tell me about it before?”. Which is kind of the Magic Moment, I think. Teacher buy-in. Once a few teachers are in, things start to shift for the better, as they seek out Synthetic Phonics professional development courses and read about it, ask a lot of questions and think critically about literacy-teaching generally. There’s not a lot of Synthetic Phonics PD available in Victoria at present, Maureen Pollard runs some at ACER, and Kristin Anthian in Werribee does too, plus the TTR4L people. I’m planning to run PD for schools this year too, either via my business or LDA (if they want me to), and will advertise it on this blog. It’s often hard to get the whole school’s attention/time, so perhaps best at first to focus on the people who are most receptive, and persuade them to attend? I’m also hoping to do the Sounds Write training this April so that I have a whole training “package” for schools, it’s a UK one but I can just adapt it to Australian English. I hope that all helps, and I’ll gladly help plead your case if you want me to. Alison

Hi Alison,

Another terrific posting which serves so well to show how a mixed methods approach is likely to confuse a child for life.

Best wishes,

John

[…] via Balanced literacy | Spelfabet. […]

Alison – what a brilliant posting! Susan Godsland has flagged it up on the UK Reading Reform Foundation message forum – and I'll do the same on my Phonics International forum.

I think the starting point is making the complex English alphabetic code truly 'tangible' with the high-profile use of alphabetic code charts. I think these are so important that I provide a very large range of them free to download – for student-teachers, teachers, parents, learners – giant ones and mini ones – all different styles!

For the Australian accent, simply say, "In Australia, we tend to pronounce that grapheme (letter or letter group) like this…" and match the accent to the bits of code – it's not difficult.

You can find the free charts here: www.alphabeticcodecharts.com

I even advocate their use from children starting out at four years old when they are being taught the 'simple code' first (that is, mainly only one spelling for each sound we can identify in speech).

I also advocate an approach which is 'two-pronged systematic and incidental phonics teaching' which, of course, is well-supported by use of alphabetic code charts. This simply means that the teacher (parent or whoever) can tell the learner about bits of alphabetic code as they arise in wider reading, in the environment, on the cereal packet – and so on.

Keep up your truly fantastic postings!

Debbie

X

Hi Debbie, thanks for the nice feedback, and links to your useful charts. I think you’re right, preschoolers and school beginners need one spelling for each sound, but parents and older kids need a structure for thinking about the more advanced code. I’m just updating my free 44 sounds picture books and will have beginners’, intermediate and advanced versions with proper photo credits (John from Sounds Write pointed out I didn’t have these quite right in the last versions) – my answer to the “My First Words” books that show tiny children lots of complex spellings, and give them the impression that they have to memorise words rather than decoding them. All the very best, Alison

[…] Balanced literacy. Leave a reply. Ask schools how they teach reading and spelling to beginners, and you're likely to be told they take a "balanced literacy" approach, combining the best of all approaches. […]

[…] http://www.spelfabet.com.au/2014/01/balanced-literacy/ […]

As a mother of two children, one on whom coped well with the whole word method of learning to read and one who, like your post saw purely "wingdings" when reading, I'd like to share my experience. I am not an educator and did not really understand the difference between whole word versus phonics until child number two could not understand or recite the 100 site words after a full school year, could not read basic sentences, hated reading and had his self esteem shot by the process. I had little assistance from the school (yes he did reading recovery, but once he finished he went backwards again) and there was only one staff member (an older teacher) who understood the phonics approach to learning to read. Luckily I had a friend who introduced me to Fitzroy reading method which as I have experienced is a phonics approach to reading which is structured and builds from simple single sounds to complex sounds. We have followed this program over the past 8 months and my son is now reading really well. He is in grade 2 this year and he was just tested at school to ascertain his reading level and I laughed when the teacher told me he did "really well at phonetic understanding". Unfortunately, I think it is left up to parents to investigate alternative methods and supplement what is taught in school, rather than schools selecting the method to suit the child. I now tell the teachers not to send home any readers I have my own and the school is now investigating this mysterious method of teaching that my friend and I are using! As a mother, I agree the sooner we remove whole word from Australian schools the better!

Hi Nicole, yes, I think when universities and education departments start actually teaching teachers how our sound-spelling system works, and schools buy synthetic phonics teaching materials, a big load will be taken off the parents of children like your youngest. The Fitzroy Readers are great, I use and recommend them a lot. Good on you for searching around till you found what worked, and let’s keep talking about this till parents like you no longer have to. All the very best, Alison C.

I agree with everything that has been said. I am a very frustrated support teacher…am enrolled in a masters module entitled understanding reading and writing difficulties and am appalled at the standards …lecturer seemed confused about syllables and blends, CVC words and phonemes. I emailed HOD and was told most teachers wouldn't know either. Would like to continue with my concerns about masters education but it would be like banging my head against a brick wall.

Hi Jane, sorry to hear about your frustrations, education faculties really do need to lift their game re literacy teaching, it’s not good enough to say the profession doesn’t know and therefore we can’t be bothered. Working for change really does often feel like banging one’s head on a brick wall, but I guess if enough of us do it, something’s gotta give! Alison

Hi Alison,

I love your website! I have been a primary teacher for about 9 years. My grad dip certainly did not prepare me well for classroom teaching, especially in the areas of reading and spelling.

I wonder if you or your colleagues might have an opinion on the current state of teacher training courses? Specifically, are there any universities that do seem to adequately prepare their teachers to teach literacy, at the undergraduate level? Also, at some stage in the future, I would be keen to undertake postgraduate training in literacy intervention and/or specific learning difficulties.

Many thanks,

Naomi

I should have added that I live in Victoria.

Hi Naomi,

Thanks for the nice feedback, sorry to hear your grad dip didn’t prepare you for the classroom. People who have done or are doing teacher training here in Melbourne keep telling me they learn little or nothing on phonology, orthography or syntax, and that the focus in literacy is the alphabet, rote learning high-frequency words and encouraging children to read repetitive texts and guess from picture, first letter and context (multi-cueing). I’ve been reading Louisa Moats’ book “Speech to print: language essentials for teachers” and working my way through the workbook, and thinking that we need such a course offered here, but it relates to American English not Australian English so some of the examples are very confusing.

I’d love to teach it to teachers but first I need to work out a way to make it economically feasible.

All the best, Alison

Thanks for your reply, Alison.

Thankfully, the one-year GradDipEd is on the way out.

The Louisa Moats book looks great. It would be a good start if this sort of text was studied in every teacher course. The set text in my course was all about "critical literacy", although there were some token phonics readings in the reader. Thankfully, I completed a linguistics major as part of my psychology degree, so I call on that knowledge often, but it couldn't teach me to be a good teacher of reading and spelling.

I noticed that you posted a link to an online course on your Facebook page. I'll certainly look into this one. Thanks also for the "Training" section of your website, which has lots of good suggestions. It would be great to hear about any other online (or other) courses you come across.

Do you have a "recommended reading" section for teachers on your website (there's so much on it, I'm not sure I've seen it all!)? I'd be interested in hearing about other books, like the "Speech to print" one you suggested.

Best wishes,

Naomi

I don’t have a “recommended reading” section on my website but I should put some links on the “where to start” pages, good idea.

Thanks

Alison

[…] Thank you Spelfabet for a fantastic post of how a ‘balanced’ reading approach might look to the children learning to read. http://www.spelfabet.com.au/2014/01/balanced-literacy/ […]

[…] in ways that set up around 20% of students to fail. The most common approach is called “Balanced Literacy“, a dog’s breakfast of approaches that contradict each other, don’t make much […]

[…] “a bit of everything” approach (widely known as “Balanced Literacy” but I call it “A Dog’s Breakfast”… and Reading Recovery are based on the underlying belief that learning to read is natural, and […]

[…] Read another good article from the spelfabet blog about the confused notion of ‘balanced literacy’ http://www.spelfabet.com.au/2014/01/balanced-literacy/ […]