Teaching spelling

0 Replies

In a Grade Prep classroom recently, I wondered why the teacher was getting the children to repeat the following sentence:

“Big elephants can’t always understand small elephants”.

Then I realised she was teaching five-year-olds a mnemonic for the spelling of the word “because”. Big elephants often can’t understand little elephants? Some days in schools, my jaw drops more than others.

Teaching spelling the word “because”

The word “because” only has one sound spelt unusually. The rest of it is perfectly sound-outable, including the “se”, typically used after a vowel digraph, see this list).

The tricky spelling is the “au”, which usually represents the sound “aw” as in “launch” (click here for more words), but in the word “because” represents the sound “o” as in “fault”, “auction”, “sausage” (and some other words, see a list here).

I tell kids the word “because” is talking about the cause of something, and we can help ourselves remember its spelling by saying “be-cAUse” not “be-cOs” when we write it.

When spelling, good spellers often say sounds with funny spellings the way they are spelt, which helps them memorise the tricky spelling. There is no need to memorise complicated mnemonics about elephants.

Current spelling research – implications for teaching

Luckily for all of us, Dr Kerry Hempenstall has recently put a long summary of the implications for practice of current spelling research on the National Institute for Direct Instruction’s blog, titled Feel like a spell?

This blog post contains lots of interesting stuff for those of us who really should read all the relevant journal articles and work out the practical implications ourselves, but we love it when someone else does it for us (thanks, Kerry).

Here are some of what I thought were the most interesting points, which I’m sure will make you want to read the whole thing for yourself, or at least the first part (which is followed by a long series of referenced quotes about spelling and reading).

- The quality of handwriting and spelling have been found to be the best predictors of the amount and quality of written composition.

- Children don’t grow into good spelling – the errors of older poor spellers are similar to those of younger normal children.

- 75% of employers are put off a job candidate by poor spelling or grammar.

- Australian children don’t spell English as well as do Mandarin-speaking children in Singapore (where English spelling is taught more systematically).

- Beginning primary teachers are not confident about teaching specific aspects of literacy such as spelling, grammar, and phonics.

- English has 1,120 ways to write the 44 sounds.

- Only 4% of English words are truly irregular.

Learners need explicit, systematic teaching, which:

- teaches children to manipulate phonemes (sounds) using letters,

- focuses the instruction on segmenting & blending, rather than multiple activities,

- teaches children in small groups (which can be tricky with one teacher in a class of 20+),

- Incorporates feedback, and massed and spaced practice.

Spelling outcomes are consistently improved when interventions include:

- explicit instruction, with

- multiple practice opportunities, and

- immediate corrective feedback after the word was misspelled – so please ignore experts who recommend banning the use of erasers, and don’t accept children’s “invented spelling”. Give credit for good attempts, then help children correct their errors.

If you can spell a word, you can usually read the word, but the ability to read a word does not necessarily predict accurate spelling. Poor spellers may have underlying difficulties with discriminating/pronouncing all the sounds in words, pay less detailed attention to letter order and patterns, and rely more on partial analysis.

Across all grade levels, systematic phonics instruction improves the ability of good readers to spell.

The impact of systematic synthetic phonics is strongest in the first year of schooling.

For poor readers, the impact of phonics instruction (alone) on spelling is small. Strugglers are very reliant on dedicated spelling instruction.

Implicit phonics (drawing attention to phonic cues in stories) is shown to be ineffective for struggling readers, as it is insufficiently intense and systematic and doesn’t give them enough practice.

Pseudo-word reading is the best predictor of spelling in primary grade children e.g., monglustamer

The physical act of writing may enhance spelling.

Spelling difficulty is not a general “visual memory” problem. It is a specific problem with awareness of (and memory for) language structure, including the letters in words.

Knowing the spelling of a word makes the representation of it in the brain sturdy and accessible for fluent reading.

Students who see the spellings of words learn the meanings of the words more easily – orthographic knowledge benefits vocabulary learning.

Traditional vocabulary instruction involves the sequence: Story – spoken word – meaning.

Research suggests it should be: Story – spoken word – meaning – pronounce – spell.

Effective spelling instruction emphasises these principles:

- knowledge of sounds,

- letter-sound association, patterns (e.g. doubling letters, “long” and other vowel spellings), syllables, and meaningful parts (e.g. past tense “ed”, adjective ending “ous”),

- multisensory practice (hear the sounds, feel them in your mouth, see the letters and feel their shape in your hand);

- systematic, cumulative study of patterns;

- memorizing a few “sight” words at a time;

- writing those words correctly many times;

- using the words in personal writing.

The aim of teaching spelling is that spelling be fluent and automatic, not just accurate.

~

I hope I’ve done this long, detailed blog post justice in simplified form, and that you’re now inspired to read the whole thing yourself.

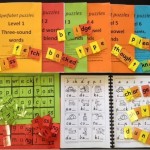

And I hope you agree that the Spelfabet materials (available here) teach spelling along the above lines.

Leave a Reply