Quality literacy teaching

5 Replies

I've just been reading a great article by Professor Diane McGuinness in the UK Reading Reform Foundation website's 2002 archives, which I found especially interesting in the light of all the talk about teacher quality in the Australian media in the last week.

It's called "A Prototype for Teaching the English Alphabet Code", and explains and describes the essential elements of a good reading and writing teaching program.

As it's 6700 words, let me just summarise it for you, after which I'm sure you'll want to read the whole article for yourself, or if you want something more recent, and have a spare hour and a quarter, you can watch a 2011 talk by Diane McGuinness on YouTube – click here for the first half-hour, and here for the second half. But beware that she is talking to an expert audience so it's a little complex and includes some jargon.

A brief history of English literacy-teaching

Mid-19th century efforts to anchor literacy-teaching in the sounds of English were overtaken in the 20th century by look-and-say then meaning-based, Whole Language teaching methods.

These focussed on memorising "sight words", reading dull, repetitive little books from reading schemes (“See Janet, see. Come, come, look at me. I can swing. See me, said John.”) and occasional, sometimes incomprehensible phonics (e.g. asking children "What's the short sound of 'o'?"). The curriculum had no focus on writing/spelling. Phonics advocates tried to change all this, but without success.

In the mid-1960s, a study of 9,000 US children by researchers Bond and Dykstra was supposed to determine once and for all which teaching methodology worked best, a phonics-based one or a whole language/basal reader one.

However, they made a major statistical error when analysing their data, which meant that their research did not compare teaching methods, it compared classrooms/teachers.

Their research was thus inconclusive about which method was best, and this was taken to mean that teaching method was irrelevant, and what mattered was the quality of the teacher.

Since it appeared that methodology didn't matter, and since learning to read had been deemed a natural process, the priority became reading books in natural language, creative writing and enjoyment. Very high functional illiteracy rates across the English-speaking world were the result.

In 2000 the US National Reading Panel reviewed published literacy-teaching research since the 1970s, and found that out of 1100 studies, only 38 met the basic requirements for a valid scientific study, having an experimental research design, a control group, proper statistics, and being published in a peer review journal.

Half of these were remedial studies, so only 20 bona fide research studies into the efficacy of beginning reading methods had been published in 30 years. No wonder not much was known about how to teach reading well.

Lessons from the past – how writing systems are designed

Examination of 5000 years of writing systems shows that no writing system, past or present, is based on the whole world. They are all based on either the syllable, the consonant-vowel unit (CV diphone), consonants alone, or phonemes (consonants+vowels), even the ones where meaning and phonetic units overlap.

The average human can only memorise about 2000 word-symbol pairs. There are 1800 basic kanji in Japanese, which take children about 12 years to learn. Highly-educated Japanese need another 10 years to learn an additional 2000 kanji. There is simply no way anyone could memorise all the words in any language by sight.

Languages organise their writing systems around only one of the four basic unit types, and no language uses a mixture of syllables, diphones, consonants-alone and phonemes.

Each writing system allows all the words of a language, and all the possible words, to be written relatively easily. If you look at how ancient schools taught a written language just after it was devised, you can see how its authors thought it should be taught.

The Prototype – Sumerian literacy-teaching

The Sumerians' literacy-teaching methods show that they did the following:

1. Thoroughly understood the complete structure of the writing system before devising a method of instruction.

2. Taught the specific sound units that were the basis for the code, and not other sound units that had nothing to do with the code.

3. Linked each sound to its arbitrary, abstract symbol.

4. Taught the elements of the system in order, from simple to complex.

5. Made the students aware that the writing system was a code and that codes are reversible (decoding/encoding) by linking writing/spelling to reading (copy-recite).

6. Designed lessons to ensure that spelling and reading were connected at every level of instruction via looking (visual memory), listening (auditory memory) and writing (kinaesthetic memory).

Our education systems have strayed very far from these logical principles, and often don't adhere to even a single one of them.

Why the English Alphabet Isn't Like Any Other Alphabet, or "Do Finns have dyslexia?"

The Sumerians had a single symbol for each syllable in their spoken language, and many languages today are similarly transparent.

Because English is derived from multiple languages, it has a more complex, opaque spelling system.

Modern languages with transparent or nearly-transparent spelling systems include Italian, Spanish, German, Finnish, Swedish and Norwegian. They are easy to teach, and most children learn them in a year.

Decoding is not an issue with such writing systems – everyone can decode – and there is no need for the tests of decoding accuracy/word attack that are used in English, in particular to diagnose dyslexia.

Some people using transparent written systems still have problems with reading comprehension and fluency, but on testing, normal seven-year-olds from Salzburg read as fast as normal nine-year-olds from London, and made half as many errors. The Austrian kids had been learning to read for one year, and the English for four or five.

I'll directly quote a paragraph from Diane McGuinness here:

"Further, when the worst readers in the entire city of Salzburg (incredibly slow) were compared to ‘dyslexics’ in London (incredibly inaccurate), the Salzburg children read comparable texts (translations of the same words) at twice the rate of the English-speaking children, with 7% errors. The English children not only read much slower, but also misread 40% of the words. When reading skill is so entirely tied to a particular writing system, there can be no validity to the notion that poor reading or ‘dyslexia’ is a property of the child, or to the mistaken belief that “there will always be poor readers.”

Phoneme awareness is highly correlated with reading skill in English, but in languages with transparent alphabets it is not. What's called "dyslexia" in such languages is actually nothing like dyslexia in English, as Austrian, Scandinavian and Italian "dyslexics" can decode and spell, they just read slower than average.

Sweden's 3.4% functional illiteracy rate among 16-25 year olds compares with 11% in Canada and 26% in the US. English-speakers' reading problems are largely a product of our opaque spelling code and the way it's (not) taught.

An artificial, transparent teaching alphabet with one spelling for each sound might be the solution.

On the Trail of More Clues to the Prototype -reanalysing the Bond and Dykstra data

It's possible to reanalyse the data from the mid-1960s Bond and Dykstra study of 9000 children, eliminating the statistical error that made it compare teachers not methods.

Two of the teaching methods in this study did introduce children to a transparent alphabet. The first one used the artificial Initial Teaching Alphabet, but as this required children to learn something then unlearn it, it wasn't efficient, and didn't have great outcomes.

The second teaching methodology was the Lippincott program, and reanalysis of the data shows this was the undisputed star program in the Bond and Dykstra research. It works like this:

1. An artificial transparent alphabet with a main spelling for each of the 40+ sounds in English, plus some alternate spellings, is introduced.

2. Lessons are anchored in the sounds of the language, and reading is taught from sound to print. Children learn that the letters are symbols for the finite number of sounds in their own speech. Sound-targeting stories feature a particular speech sound.

3. Children learn to segment and blend phonemes in words for both reading and spelling.

4. Children learn letters by writing them, not from looking at them or from letter tiles. They say sounds (not letter names) as they write letters.

5. Reading and spelling are integrated.

6. Reading materials are designed to correspond to the level the child has achieved.

The mainstream basal reader programs performed very poorly when the data were re-analysed to compare programs rather than teachers. Children in these programs even performed more poorly on the "sight words" they had been memorising all year.

Some "literacy" activities help children, and others have a neutral or negative effect

In 1966, researchers Chall and Fieldman discovered through classroom observation that what teachers said they were doing only bore a vague resemblance to what they were observed to do in the classroom.

Three large-scale studies starting in 1985 investigated this further, across a variety of classrooms and methodologies, and all found the same things. I'll quote Diane McGuinness' words again here, because I can't put it more succinctly:

Very few ‘literacy’ activities for young children (ages 5 to 8 ) have a positive impact on reading skill. Those that do are: learning the phonemes in the language and how they are represented by letter symbols, segmenting and blending sounds in words, plus the amount of time spent writing (all types). There was some evidence that silent reading (not reading aloud, or group reading) is helpful, especially if the whole class is reading silently at the same time.…

Many literacy-type activities had no impact on reading skill (neutral), and some had a strongly negative impact, meaning that the more time the children spent doing that activity, the poorer their reading scores were. The strongest negative predictor was teacher-directed language arts lessons involving vocabulary training and reading stories. This was a powerful effect in all three studies, and negative correlations ranged as high as r = -0.80 (1.0 is perfect). Time spent memorizing ‘sight words’ was also a strong, negative predictor. Activities that had no impact, positive or negative (correlations at zero), were ‘pretend reading’ or ‘group reading,’ learning ‘concepts of print’ such as print direction and how to turn pages, tasks involving letter names, time spent on larger phonetic units, such as clapping out syllable beats, and time spent on auditory phoneme awareness tasks (no letters). The message is clear: If your goal is to teach the alphabet code, then teach the alphabet code, and get on with it.

The positive impact of writing was seen in all three studies, and was something of a surprise. Experimental studies have shown that copying letters is the best way to learn them. Not only this, but copying out spelling words halves the learning rate compared to using letter tiles or a computer keyboard. There is also evidence that learning to spell produces higher scores on a reading test than the same amount of time spent learning to read, a result that confirms Montessori’s insight about the greater generality (transfer) of spelling over reading.

What to look for in a reading/spelling program

Based on the above research and analysis, here’s what Diane McGuinness recommends reading/spelling programs should adhere to:

- No sight words (except for truly undecodable words like "choir" and "sure").

- No letter names.

- A sound-to-print orientation, as sounds, not letters are the basis for our spelling code. Sounds provide the pivot point which allows the system to reverse, so that what is encoded can also be decoded, unlike trying to teach a sound for all possible spellings.

- Teach phonemes only, not other sound units (e.g. syllables, blends/clusters, onset and rime).

- Begin with an artificially transparent alphabet – the most common spelling for each sound.

- Teach children to identify and sequence sounds in real words by segmenting and blending using letters (don't work with sounds alone).

- Teach children how to write each letter, and integrate writing into every lesson.

- Link writing/spelling and reading, to ensure children understand how the code works.

- Teach spelling alternatives (“there’s more than one way to spell this sound”) not "reading alternatives", and not just the basics but also 134 advanced spelling alternatives.

- Spelling should be accurate or, at a minimum, phonetically accurate.

The National Reading Panel results

As mentioned earlier, the NRP found that most of the published reading research wasn't proper scientific research at all, but 20 classroom studies were able to be used to compare beginning teaching methods, with the differences between methods expressed in Effect Sizes (ES).

An ES value of 0.3 or less means there wasn't much difference between methods. ES values of more than 0.5 show that one method is clearly superior to another, and an ES of 1.0 or more means a large difference between methods.

Both synthetic phonics programs like Lippincott and analytic phonics programs (where learners start from words and other larger-than-phoneme units, not sounds) were included in the meta-analysis, but even then, the effect size in favour of phonics over whole language programs was 0.55.

The National Reading Panel only looked at research from 1970 onwards, and thus didn't include the 1960s Bond and Dykstra study of 9000 children mentioned earlier. Diane McGuinness added their data to the NRP data, and re-analysed the statistics.

The Lippincott program, which most closely approximates the above prototype reading/spelling program, had effect sizes as follows in the Bond and Dykstra data, which was from over 1000 children: word recognition 1.12, phonics knowledge 0.62, spelling 0.61, comprehension 0.57.

Jolly Phonics and Fast Phonics First

Jolly Phonics is a synthetic phonics program about which there were data in the NRP, plus there were also more recent studies which could be re-analysed. This program puts the kybosh on a lot of the myths about teaching very young children to read and spell in a classroom format, and makes synthetic phonics straightforward and fun, with an action for each sound, a fast pace, lots of writing and decodable books.

In one study in Scotland, effect sizes were 0.9 immediately after the training, 1.0 a year later and 1.1 a year after that.

A study in an impoverished area of London where many of the children arrived at school with little or no English found ES values of between 0.63 and 1.4. Even though these children scored much lower than average on vocabulary, a year later, ES values were still between 0.62 and 0.86.

A Canadian study looked at the use of Jolly Phonics mixed with other methodologies and spread out over a whole year, with about half as much teaching time devoted to it, and still found ES values of between 0.44 and 0.68.

In Clackmannanshire in Scotland, a program similar to Jolly Phonics called Fast Phonics First was compared with a typical, analytic phonics, one-sound-per-week at word beginnings approach. FPF won hands down, with ES values of 0.91 for reading and 1.45 for spelling.

Both Jolly Phonics and Fast Phonics First children maintained their advantage over time – see the article for precise details (I tried summarising it, but it's a bit like comparing apples and oranges).

Teaching phonological awareness without letters is a waste of time

Another group of children in this study were taught phonological awareness (learning about sounds in the absence of letters) as well as analytic phonics. They also ended up well behind the FPF kids, with effect sizes of 0.85 for reading and 1.17 for spelling.

This suggests it's a waste of time teaching children phonological awareness (clapping syllables, rhyming, hearing beginning or ending sounds) in the absence of letters. This is backed up by studies of auditory-only phonological awareness training the NRP data.

Spelling research

As for research focussed on spelling instruction, or on the impact of teaching the whole spelling code not just the simplest parts of it, at the time this article was written it still hadn't even begun.

OK, that's my summary of the article, and you can read the whole thing here. Don't forget that this was written ten years ago, and since then more research has been done which strengthens the arguments in favour of synthetic phonics.

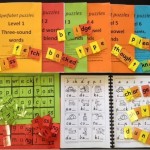

I hope you agree that the Spelfabet materials available from this website's shop, if used as recommended, are consistent with the core elements of the reading/spelling program Diane McGuinness recommends, though they're designed for older, struggling readers/spellers, not absolute beginners.

[…] http://www.spelfabet.com.au/2013/03/quality-literacy-teaching/ […]

Hi Alison,

That is such a good article by Diane McGuiness, isn’t it? I keep finding myself going back and re-reading it.

It has reminded me of a question I really struggle with regarding phonological awareness: I’m comfortable with recommending that phonemic awareness tasks be embedded in a high quality, synthetic phonics program as they should be (so they are not taught separately) in Prep (in Aus) but what should we recommend regarding Phonological Awareness goals in Kindy? It seems like Diane is saying that working in Kindy on syllables, rhyme and hearing first and last sounds without letters is a waste of time (and it would seem pretty weird to be doing the syllable and rhyme activities with written words involved) but I was inclined to think that there would be some benefit to be had from being aware of these larger chunks of sound before code-based instruction begins as it often does in PP. I know Theresa Ukrainetz advocates a ‘start and stay with phonemes’ approach to Phonological awareness but I don’t know what she would say about what to do in the Kindy year which I think they call preschool. What do you recommend for Kindy?

Cheers,

Juliet

Hi Juliet, yes, I seem to always have something or other by Diane McGuinness in my “to read” pile and my copy of “Why Children Can’t Read” is totally dogeared and falling-apart-y.

I also struggle with what to say to parents about phonemic awareness before school starts, and usually end up suggesting that they focus on learning some letters plus the basic concept that words are made of sounds and letters are how we write down these sounds. So instead of using the iPad for edutainment (I am in a middle class suburb and EVERYONE seems to have an iPad), I ask them to use Bob Books, Reading Raven, Pocket Phonics, Phonics Hero, Little Learners Phase 1 and similar apps, plus the Dandelion Launchers iBooks, and I encourage the parents to help them learn to blend by listening to sounds and discerning the words. I sometimes ask parents to model segmenting, e.g. when writing the shopping list, say each sound as you write it if the child is watching. This gives children an accurate idea about how spelling is done. I also encourage all the usual rhyme and alliteration that is typically going on in preschool anyway because its fun and we know it may help with literacy, but usually I don’t kick in with a lot of phonics intervention stuff till a child is in school. They just have too much oral language and articulation work to do if they are on my caseload. I’ve given up working on phonemes in the absence of graphemes, it’s pretty meaningless. Hope that’s helpful, and I’d be interested to hear what you do, too. Alison

Hi Alison,

It’s always great to see the work of Diane McGuinness being acclaimed. She is an academic who not only had a first-rate understanding of the research and how to interpret it but she also knew how phonics should be taught in the classroom. One sees all these research articles and not a one includes her name in the references. When I see so many academics pushing old-fashioned print-to-sound approaches that don’t work well for the lowest 20%, I want to hold my head in my hands.

McGuinness’s prototype is absolutely spot-on and has had huge influence on the way modern phonics is taught in the UK. What a pity her own country (as well as many in Australia and New Zealand) doesn’t seem to be listening. If they followed her advice, they’d be getting the same kinds of results we get in schools where Sounds-Write, which contains every single one of the criteria in the prototype and then some, is being taught.

I’ll bring you a brand, spanking-new copy of Why Children Can’t Read when I see you in Perth in April of next year.

Keep up your excellent work!

Best,

John

Hi John, I agree, when I first read Diane McGuiness I just had lightbulb moments every few pages, I don’t understand why she gets so little credit and why not everyone knows about her work. The sound-to-print orientation is what makes the difference between a system that is completely reversible and seamless and one that is far too clunky and complex and never really makes sense. Looking forward to seeing you next year too, Alison