Edubabble

3 Replies

I had an interesting conversation the other day with an old friend whose father is a Mathematics professor, and whose daughter has a diagnosis of dyslexia.

She said her father is very annoyed at the way the word "numeracy" has kind of taken over in education from words that actually mean something about mathematics, like arithmetic or probability.

"Numeracy" has become this kind of over-arching heading for all kinds of things, important and unimportant, that are vaguely related to numbers and quantification. For example, children might "do numeracy" by colouring by numbers.

Meanwhile, he worries that the average learner understands less and less that really matters and is interesting about mathematics. For example, can students do sums, or estimate how much should be in their bank account, or how heavy an object they're about to pick up is likely to be, based on its materials?

New, critical, multi, 21st century literacies

Then this afternoon I had a fairly heated discussion with someone at school who is very keen on technology and all the latest newfangled literacy lingo, and thinks learners should use keyboards not handwriting, and iPads not worksheets. He thinks the question, "but can children read and spell?" is oldfashioned and irrelevant, and what matters is postmodern, contextualised, 21st century digital literacy.

It made me think of one of my favourite jokes: "What do you get when you cross a postmodernist with the mafia? An offer you can't understand". How do we even know postmodern contextualised 21st century digital literacy is a thing?". Certainly not experimental evidence.

Upon reflection on these two conversations, I think I now have a distaste for the word "literacy", and am going to avoid it, and say "reading" and "spelling" instead.

"Literacy" has come to mean just about everything and nothing to do with language, and education is awash with discussion of "new literacies" and "critical literacies", "multiliteracies" and "21st century digital literacies".

Having started work in schools in 1989, and worked a lot with technology, I've seen a lot of fads and jargon come and go, and it's all too familiar.

How are each of these literacies actually defined? How are they measured? How do we know they matter? Where are the data to show that they are teachable and being taught well, not just skills kids are learning independently on Facebook and Twitter?

Scaffolding is meant to be temporary

To participate effectively in computer-based written communication (which seems to be what most of these new literacies are about), you need to be able to read and spell.

Yes, you can find a whole lot of scaffolding tools to make up for your reading and spelling deficiencies, like spellcheckers, talking word processors and word prediction, but they're like using floaties and kickboards indefinitely while trying to do laps of a 50 metre pool. They slow you down and don't disguise the fact that you aren't doing it all on your own. Miss steaks I kin knot sea, etc.

Because I'm a speech pathologist, I don't get to see much of the learners who are soaring like eagles in their new, critical, multi, 21st century, whatever literacy classes. Good on them.

I get to see the kids who continually flap off the cliff, flip into a spiral and crash to the bottom, and they and their teachers both know it. No amount of clever technology, or saying reading and spelling aren't important nowadays, stops this from being a serious problem.

Questions that do matter

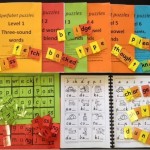

The questions I first want answered about these kids are: 1. Can they hear the individual sounds in words, and blend and segment them? and 2. Do they know how these sounds are represented by letters? That is, can they decode and encode text? And if not, who's teaching them?

These are absolutely necessary, though not sufficient, skills that can end up getting pretty lost in the pursuit of the latest bright shiny thing. After that, I want to know: How are they going with fluency, vocabulary and comprehension?

After that, and on the day I can go into a secondary school and not find any students who are reading at a level ordinarily expected of a child aged 6, 7 or 8 when they are 12, 13 and 14, I'll start being more interested in things like new, critical 21st century multiliteracies.

Apropos, considering the conversation I had yesterday with the principal of a certain private day school for students with learning disabilities. He kept saying: Visual perceptual! Comprehension! Visual integration! Distracted by by too much visual information! Visual attention! I kept saying: Smart kid! Can't read, can't spell! I often wonder if fancy words are a smoke screen used by many to hide the fact that they don't know what they're talking about.

Hi Holly, sorry, I only just saw your comment buried in a mountain of spam. I agree that people often use jargon and big words to embiggen themselves and hide a lack of the understanding which would allow them to communicate more clearly and simply. Good luck with the evidence-based intervention with the smart kid, and great to hear you’re on his/her case.

Thank you for writing this article. It rings true with some of the practices we see in Higher Education. Folk chasing baubles when actually what they need to do is just get on with teaching. We are being pushed into minimising how much time we spend on marking and told that students only need to demonstrate competency in a skill once. They don’t need to learn the names of parts, or do dissections in order to understnd the field – biological alphabet etc