Do we need spelling reform?

11 Replies

Every NAPLAN season there are complaints about English spelling complexity, calls for one-letter-for-each-sound spelling reform, and people wondering why we still bother with spelling, now we all have a spelling chequer that came with our pea sea.

Switching to a one-letter-for-each-sound system would mean huge changes, such as adding an extra 18 letters to our alphabet's 26 letters representing 44 sounds. Simplifying spelling would also mean losing the rich source of information about word meanings and origins embedded in our current spelling system.

Give Samuel Johnson a break

Famous smartperson Samuel Johnson published the first major English dictionary in 1755, thus stamping out the spelling rapscallionship of the likes of Shakespeare, who routinely spelt the same word two or three different ways in one sonnet, and his own surname 14 different ways.

Unfortunately Johnson didn’t then write another book explaining the logic behind his system, but it’s extremely well and carefully done, and deserves more understanding and appreciation. Or at least not quite so much slagging off.

Linking related words

For example, it seems crazy to have lots of words with “ea” for a sound that’s ordinarily just an “e”, like bread, breakfast, feather, weather and dead. Let’s change them to “bred”, “brekfast”, “fether”, “wether” and “ded”, and write “sez” instead of “says”, like rappers do.

This would destroy the written connection between "say" and "says", and disconnect the two “reads” (as in “I’ll read Shakespeare when I retire ” versus “I have smugly read it”) as well as “mean-meant”, “deal-dealt”, “dream-dreamt”, “heal-health”, “leap-leapt” and “steal-stealth”. It would remove the "south" from "southern", and the "Christ" from "Christmas".

These days, only toffs pronounce the “t” in the word “soften”, but losing it would weaken its connection to “soft”. The word “sign” doesn’t seem need a “g”, till you consider "signal", “signature” and “insignia”. The same goes for “malign-malignant”, autumn-autumnal”, “solemn-solemnity”, “phlegm-phlegmatic”, “diaphragm-diaphragmatic”, “crumb-crumble” and “limb-limber”.

It’s not true of “bomb-bomber” or “plumb-plumber”, but pronunciations change over time – consider how many Australians (quelle horreur) pronounce “picture” and “pitcher” as homophones.

The Romans had plumbers, poisoning everyone with lead pipes, and Guy Fawkes died in 1606, so bombers aren’t new. Perhaps in Johnson’s day they said the “b” out loud.

When someone cracks time travel, my hand’s up to go back and have a listen. By then, Indian English will probably have achieved world domination, and we’ll all be saying the “b” again anyway.

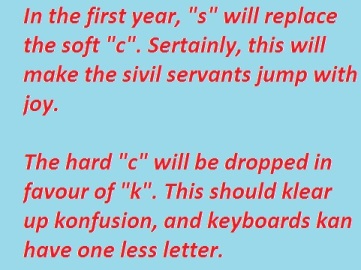

C is nesessary and rekwired

Why do we need a letter “c” when we have “s” and “k”? Well, for starters, it connects words like “electric-electricity”, “critic-criticism” and “politics-politician”.

If we got rid of “ti” and just used “sh”, we’d disconnect “act-action”, “direct-direction” and “opt-option”. The same goes for “si” in “precise-precision” and “ssi” in “aggressive-aggression”.

The language’s historical roots are reflected in “dental”, “moist” and “sculpt” and in “denture”, “moisture” and “sculpture”. Do we really want to trash that and write “dencha”, “moischa” and “sculpcha”?

Root words can tell us a lot about meaning. When farmers first heard of “fracking” they knew from “fracture”, “infraction” and “fractious” it was breaking, but probably not good, news.

Diverse dialects

Standardising English spelling meant taking into account a variety of dialects, and our spelling system is flexible enough to accommodate such variation.

Geordie and American kids can file the “a” in the words “grass”, “pass” and “last” in their heads alongside “cat”, “bag” and “fan”, while Londoners and Aussies can put it with “father”, “spa” and “drama”.

The Scottish “put” goes with “flu”, “hula” and “tutu”, in Australia it goes with “bully”, “Muslim” and “octopus”. “New” sounds like in “coo” in the US, and like “cue” across the Atlantic, but its spelling stays the same.

You say “neither” (as in ceiling, protein and Sheila) and I say “neither” (as in eiderdown, kaleidoscope and seismic) and nobody feels compelled to call the whole thing off.

Language of origin

Dr Johnson retained many word origins in spellings, so we have a Greek “ch” in “school”, “chemist” and “mechanic”, a Greek “y” in “gym”, “cryptic” and “symptom”, a Greek “ph” in “phone”, “graph” and “sphincter”, and a Greek beginning “x” in “xylophone”, “Xerox” and “Xena the Warrior Princess”.

“Ch” in “chef”, “brochure” and “parachute” comes from French, “th” in “birth”, “they” and “feather” from Old Norse, courtesy of the Vikings, “x” in “box”, “fax” and “sexting” from either/both Germanic and Latin. Don't forget the tribes of Europe were invading each other and nicking each other’s words for milliennia, so it’s often hard to work out who said it first.

Lots of spellings come from French, thanks to 1066 and all that – the “é” in “café”, “paté” and “resumé”, the “ee” in “fiancée”, “melée” and “matinée”, the “t” in “ballet”, “parfait” and “rapport”, the “oi” in “croissant”, “soiree” and “noisette”, and the “tte” in “baguette”, “laundrette” and “cigarette”. Johnson wisely chose not to ditch spellings from the language spoken just across what Kiwis would call the dutch.

Words with vowels like “cat”, “bet”, “din”, “rob” and “duck” tend to be Germanic/Old English, whereas vowels like “cape”, “grebe”, “dine”, “robe” and “duke” tend to be later borrowings from French/Latin. Each invasion and migration brings new words – “schmooze” and “schlock” are from Yiddish, “galah” and “coolibah” from Yuwaaliyaay, “gunyah and “waratah” from Dharuk.

Separating homophones

Having multiple spellings for most sounds also allows us to more readily differentiate in print between English’s many homophones – “by-buy-bye”, “plane-plain”, “doe-dough” and Homeric “d’oh”, “Pulitzer Prize” and “pullet surprise”.

Why do we make spelling a bore and a chore?

If we all understood spelling better, perhaps we’d stop wanting to dumb it down, start enjoying and celebrating its diversity, flexibility and deep historical roots, and put an end to the practice of “doing spelling” in schools by getting children to memorise lists of words with unrelated spellings.

actually, you said a bunch of factually incorrect things there. I research etymology and languages as a hoby, and let me give you the truth about this matter, with plenty of facts to back it up. English spelling has no consistent rationale whatsoever. Every possible rationale you can name has a bunch of counterexamples involving common words that it does not even take a 5-minute internet search to find. For instance, the morphological resemblance has quite a few failures that phonetic spelling would fix; for instance why do we have “cat”, and ‘kitten; “high” and “height”; “speak” and “speech”; “deign” and “disdain”; to name just a few of many morphological resemblances that English spelling actively masks; all of them words that come from a common root, and have the same sounds, but those are written differently (letters which spell the same sound differently are in bold in my text); seems like a morphological spelling system would spell the same sounds the same in those words, yet English does not. Besides false negatives, English spelling has countless false positives in the department of morphological spelling. Are the following pairs of words connected, “Meant” and “mean”; “Pain” and “paint”; “Gain” and “again”; “Her” and “hero”; “Fur” and “fury” “rein” and “reinvent”; all of these are common words where the spelling implies a morphological connection that is not there (letters in common written in bold, and letters pronounced differently in the other word [which are what implies the morphological link that does not actually exist] written in bold, italicized and underlined). Once again I could document hundreds more but that might take all day, or longer. How do you explain all the words I have documented above. English spelling is also not truly etymological. You do realize that English spelling never treats the earliest form of a word as its spelling, but it is always a later form. If we were to write each word in the oldest form known to the English language, we would spell “lord” as “hlaford”; “woman” as “wifman”; “the” as “þæt” (or “thaet” if we are to use modern character sets) to give three out of thousands of examples. We do not do that. There is not a single case where we do. Invariably some later form of the word is what is written yet at the same time, it is often not how we pronounce it now. Furthermore, the etymologies English spelling reflects are often ones linguistic scholars know are false. For one example, there is the “s” in “island”; in Shakespeare’s time the word was spelled “iland”, which is still how it is pronounced. the “S” was inserted by pretentious jerks who thought that the spelling should reflect its origin in the Latin word “insula”; only there is one huge problem with that; island is not derived from insula at all! they do have a coincidental resemblance, but no derivational link (unless you care to count some proto indo european word both descend from); seriously, ask linguistic scholars, island is in fact a pure germanic word; having no connection to Latin, and being documented in old English, where it was spelled and pronounced “iglund”, so if the word was to have a vestigial or etymological letter, the correct one would be a g, not an s. if etymological spelling is to have any value at all, it would be in pointing out the correct etymology when there are false ones floating around that may seem plausible. Yet English spelling not only doesn’t point out the correct etymology, it actively perpetuates the false one! I have yet to meet a proponent of etymological spelling who wants to change the “s” in “island” to a “g”; I should add that the claimed connection to “isle” amounts to circular reasoning as that letter was inserted around the same time to try to connect the word to “insula”, isle is actually derived from French, not Latin; and there it is spelled “Île” (notice the lack of an s there). [side note: even if they wanted to connect those words to “insula”, why wasn’t an “n” inserted at the same time?] at least a quarter of the ‘etymological letters’ in English orthography are based on assumed etymologies that linguistic scholars now know are false, so even the etymologically accurate spellings become suspect. Even ignoring that, there is no consistency in what the cutoff date for fixing the spelling of a word is; for example the “B” in “debt” is supposed to reflect its Latin etymology, but English does not get the word debt from Latin directly, the word entered English through French, where it is “dette”, so there is no “b” (the B disappeared completely from the French spelling over a century before the first citing of the English word); on the other hand, hundreds of words that English derives from Latin through French have silent letters that are missing in Latin, but there in French. As another example, the “g” in “foreign” and “sovereign” suggests a connection to “reign” which is etymologically untrue. English spelling even manages to link words to the wrong word in their language of origin on occasion; for instance the “g” in sovereign points to a connection to “Regnum”(kingdom), when the actual Latin word it is derived form is “super” (above), even that is only through the French word “soverain”; the “C” in scrisors has a similar origin in etymological blunders. English spelling sometimes tells lies that are the exact opposite of the truth about a word’s history; for example the words “rain” and “reign”, both used to be pronounced with a g in front of the n, but they lost it later at different times, only the word that lost the sound of the g first is the one which is still written with a g while the one that kept that sound for longer is the one written without the g! I should add that etymological spelling is kind of ridiculous anyway. Etymology is very interesting, I will give you that, but it is not something most people should be bothered with.

Another fact about spelling according to etymology, is that I actually makes it so that the research materials for future etymology will never come into existence. Thus changeless spelling ensures that the future history of words cannot be traced. To etymologists, the changes in the written form of a word are the easiest method of documenting the sound changes that inevitably happen. If sound changes but spelling does not, all future scholars know is that a word like this once existed, and that it has a modern form, but as to how the first one became the second it is hard to know. Often language changes radically, but it rarely changes suddenly; so as a result, the transitional forms can usually provide the answer. However, the transitional forms can only do that if knowledge of them can be obtained. If the spelling keeps up with the pronunciation, scholars can look at the word’s older forms, and say “because it lost this letter in this decade; we think people stopped saying it just before then” and use that to create a record of every transitional form the word has gone through; but if the spelling does not change as the pronunciation does, there is often no record at all of the transitional forms, meaning it is difficult, if not impossible, to explain how the older word turned into its modern form. Should we destroy the method of recording future history in order that people be more aware of past history?

Spelling cannot record the entire history of words, only a small and arbitrary selection; If we want our spelling to record the entire history, we should write each word in its earliest form, the in parenthesis place every known stage it has gone through in chronological order, finishing with the present pronunciation in phonetic spelling; for instance, we would have to write “name” as “*no-men (naman; noma; nama; name; naem)”; I probably left out a couple stages, but you should get the idea.

I should also add that the history of words, while interesting, (I research it myself quite a bit as a hobby), has little bearing on their current meaning. In English, as in every language about which anything is known about it’s history, there are words where the etymological meaning and the practical meaning are amazingly different. For instance, if I called you “a Villain”; you would not think “so he said I am a person from a rural settlement”; “person from a rural settlement” is the etymological meaning of the word in fact, very different from the modern definition of “Villain”. Most people are not etymologists and tying them to centuries out of date spellings is like chaining a large history book around everyone’s neck while they try to function. I should add that etymologists will know the origin of words anyway, whether the spelling indicates it or not, and in fact will know even if etymological spellings point in the exact wrong direction. Etymological connections are easy to make for those who know both languages, but no amount of etymological spelling can contain anything meaningful to anyone who has no knowledge of the language from which the word comes. Do you seriously think that the Italian etymologist, or even sometimes a simple person who has taken Greek as a foreign language cannot identify the development of “filosofia”; from “φιλοσοφία”; both mean “philosophy”, by the way. The way to learn etymology is to research it, learn earlier forms of the language, and read old books; not writing extraneous letters in modern words. Reading Geoffrey Chaucer’s writings will give you more useful information about etymology then spelling ever could.

I will not comment on Samuel johnson’s intelligence overall; but he was not qualified to fix the spelling of english. Many brilliant people act like utter morons when confronted with a topic about which they no nothing. Samuel Johnson knew a great deal of Greek and Latin, but about the history of his own native language, he knew nothing, yet still cared even less. It is an established fact that he did not know old English. If you have read the first page of Beowulf in the original out loud, whether you understood the words you are saying or not, you have been exposed to more old English then Samuel Johnson. Scholars are still unsure if he even knew English was a Germanic language! I should add that etymological research was in a very primitive state and based on guesswork in that era generally, but there would have been others who would have done a better job then Johnson in fixing the spelling of English. He actually thought it distasteful to write a friend’s epitaph in English, and wrote his dictionary of it purely for the money. I am certain Samuel Johnson would have written an excellent dictionary of Latin, but of English we are lucky he somehow managed to only mess up the spelling. Not all of his spellings are still in use, though to many are; calling his spelling a logical system is insane given that some of these spellings were used by him: “uphill”, “downhill”; he didn’t spell uphill and downhill with the same number of L’s; he made similar blunders with interior and exterior. He seemed to prefer spelling that pointed rightly or wrongly to Greek and Latin; seemingly in order to show off his classical education, and probably while wishing he was writing a dictionary of those languages instead. He also could not be bothered to have any consistency in how he spelled words, nor did he bother to spell words in his preface the same way he spelled the same word in the dictionary itself.

As for the dialect issue, can you understand other dialects of English in speech? if so, phonetic spelling will be intelligible across dialects. I should add that if we have hit the Dutch and Afrikaans situation, I would rather know about it right away so that I can start learning some of the other languages English has fragmented into, they should still have plenty of cognate words if we find out about it as soon as it happens. would you rather continuing to persist in the delusion that we speak the same language when we do not, and only find out centuries after the split is complete, when the languages have developed different grammatical structures and cognate resemblance has started to wither away?

Another thing is that Johnson had no sympathy for people without photographic memories. At the time, literacy was for a small elite, and the common man could get by without it. Now we purport to believe that literacy should be universal, well, guess what, hard to master systems always have a significant portion of people who fail and will never get it. Even those who do will take a very long time compared to learning a simple system. You would have to be able to rewrite the laws of physics to change that. English spelling requires memorization, not intelligence, I can explain to you what is in particular articles of the constitution of india, or tell you what “self embracing absolute power” is, or say hello in Irish Gaelic, so I am fairly intelligent; but I still struggle with English spelling. If a person like me with an Associate of Arts degree, understanding of some abstract philosophical concepts, and considerable grounding in linguistic terms, among other things; cannot understand English spelling, what chance do small children have? That is why I want English spelling to be reformed. Was it “dumbing down” to switch to decimal currency, or the metric system, or to adopt an alphabet instead of hieroglyphs? A question for you, is literacy for everyone, or just a small elite? that should determine if it should be made easy. If you are against spelling reform, come out and own it, say you believe reading is an elitist thing that not everyone needs.

Thank you for your essay, I’m going to assume that most of your questions are rhetorical in nature and not respond to them, as that would mean having to write a virtual essay myself. I agree the process by which we arrived at our current spelling system wasn’t perfect, and if we had our time over again it would be nice to make it a bit simpler, but I’m not the person who made it up, or someone who can change it. I don’t think there is much hope of changing it much, as 1.35 billion people are using it, in every country in the world. There’s no official authority in charge of English spelling any more to whom one could appeal for this change. The last time it was substantially changed, by Noah Webster, I think it was made a lot worse, now many words have two spellings not one. The best we can do is teach it well, so that all English speakers can understand and use it. Literacy for everyone. That’s the point of this website.

noticed that you completly dodged my points, there are a lot of them i will admit, but it would be nice if you replied to some of them, as just ignoring fact that debunk your points makes it look like you are disingenuous. literacy for everyone is impossible with the current state of english spelling. as hard as reforming spelling may be, acheiving universal literacy in our current system is even harder. our current system is so inchonerint that only flat out memorization of individual words can work, the flaws i highlighted are but a small number of examples among thousands, english has the most inconsistent orthography of any language on the planet; and almost anything would be better then it. at least chinese is honest about having to memorize everything. having everyone able to use a hard to master system is literally impossible, unless you can rewrite the laws of physics, it will never happen in a trillion years. the thing that annoys me the most about difficult writing systems is when people expect universal literacy or even mass literacy from them. if you admit reading and writing is for a small elite, at least you get points for honesty. i do have an alternative to organized reform and that is “deregulate and let the market decide”; abolish the idea of correct spelling, and let people spell how they think the word sounds to them. until the 1600s that was how we did things, such a system allows “plausable spellings” to get through, but blocks truly bizare ones; the consequences of bizare ones being not being understood; for instance if you spell “fight” ‘zpxjq’, no one will recognize what you wrote, but if you spell it ‘fite’ or ‘phight’ the word can be recognized even if it is not “correct”; the doctrine of correct spelling has killed the ability of written english to evolve and adapt it; and current spelling forces us to write a half fictional dead language instead of the one we speak. abolish correct spelling and in a few generations english will have a workable phonetic system created by millions of individuals free choice. i am confident that is people are allowed to choose for themselves to use a phonetic system or our current system, most will choose to spell as they pronounce. besides who gave samual johnson the right to be the totalitarian dictator of our language for all eternity? if you insist we should stick to his spellings on all words then you have made him that.

Hi Noah, I’m not actually responsible for our spelling system, and I don’t have time to go through your comments and respond to every issue you raise. They are all related to the bigger-picture question of whether English spelling should be reformed, and I’m actually not interested in this question because I don’t think it’s possible, there is nobody in charge and too many people are already using the existing system. This website is about teaching the system we have well, not arguing about whether it should be changed.

you completely seem to defend the status quo to the hilt with no regard for the possibility of improvement; do you believe 1755 was perfect? if you defend something you are obligated to explain it when someone points out flaws. you cannot respond to all of my points so you respond to none of them; do you concede that the facts are on my side, try responding to some of them; i chose but a small sample of the number of examples I could have, I could literally write an entire book containing just a list of contradictions and absurdities in English spelling; the thing you claim “is a very logical system”; given to us courtesy of a man who spelled uphill and downhill with a different number of L’s! languages that fail to change die; and yes languages can reform their spelling, check out Irish, which had an orthography that was long unchanged, having barely shifted since the 1490s; then in 1947, the language revised its orthography; and literacy became easier. also did you completely miss the point about simply deregulating spelling? no active action needed; just cessation of certain things. give a few generations of no standardized spelling and the problem will fix itself; just teach the letters of the alphabet and their sounds; then let people figure out for themselves how to spell words. part of the mess we are in could be solved through simply ceasing to correct spelling mistakes in the education system. if some people write words with silent letters and some without the free choice will eventually favor those without. the system we have is the most incoherent writing system any language has ever used. there is no way to teach it without memorization. logic, common sense, and analogy are actually harmful in understanding English spelling. it arguably deadens the mind to reason to learn it. wanting literacy for everyone in a system that may as well be designed to make being able to read and write as hard as possible is like wanting to commit a genocide but have no one die. that is impossible because the two things are contradictory; therefore, getting one precludes the other. in a debate where one side brings up a bunch of specific and clear facts, but the other speaks in platitudes I am inclined to agree with the person talking about concrete realities.

Jon, I don’t like being harangued, and I’m less than not interested in arguing with you about the rights and wrongs of something that neither of us are in a position to change. Also, English sentences start with capital letters, and I’m not ‘obligated’ (the word is ‘obliged’) to engage in pointless arguments with you or anyone else. Over and out.

I think you’re being a little defeatist in saying that we’re doomed since there’s no authority in charge of English spelling. I think that makes the English language fully democratic so we can make it what we want.

Well, yes, we are always making up words like ‘blog’ and ‘glamping’ and adding and forgetting words, that’s why there are new editions of dictionaries, and I guess the English we speak today is very different from what Shakespeare spoke (I love this YouTube video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3fvmcnRhTP8) and in 400 years’ time English will be as different again. The wisdom of crowds! But some things from Old English that seem weird but are still in the language are likely to be hard to dislodge, and I’m not sure it’s a good idea as (for example) the three spellings of ‘to’, ‘too’ and ‘two’ all carry semantic as well as phonemic information, whereas if we standardised our phoneme-grapheme correspondences we would lose the semantics, and extracting meaning from text would be harder.

I can’t say I agree with your logic there. Homophones could become more confusing with a completely phonetic spelling system, but some allow for more than one representation for a sound. For example, using the guidelines of Interspel you could differentiate between to, too and two using tù, too and tue. The three words are clearly differentiated and does away with the silliness of trying to make an ‘oo’ sound with a single ‘o’. That said, Interspel also argues for the retention of the 100 most commonly used words as well as any that carry important information on their etymology (such as retaining the -tion suffix for example). So, we could easily do away with some of the more non-sensical word spellings while being more conservative with others. Finally, for every homophone that could cause a problem with spelling reform, there is also a phonograph that could be fixed. The word ‘use’ for example, could become ‘uze’ as a verb and ‘use’ as a noun. I think that could be very helpful..

*homograph, not phonograph.

But then adding the suffix -ful to the word ‘uze’ would give you ‘uzeful’, or else you’d have to change the spelling of the base word back, and lose the connection between base and derived form. English spelling is based on phonemes AND MORPHEMES. If we go for an entirely phoneme-based system, we lose the ‘music’ in ‘musician’, the ‘magic’ in ‘magician’, and the person who fixes your broken appliances would be an ‘electrishan’, and the stuff in the wires would be ‘electrissity’. A phoneme based system would take the ‘act’ out of ‘action’ and the ‘predict’ out of ‘prediction’. We’d lose the ‘tw’ connection between ‘two’, ‘twice’, ‘twelve’, ‘twenty’, ‘twilight’ and ‘between’, and lots of other subtle, interesting things that make English orthography about the most efficient way to transcribe our both the sounds, word structure and meanings of English, given multiple accents. Whether you say ‘foot’ like a Scot or a Jamaican, it still makes sense to spell it with ‘oo’. Samuel Johnson and team didn’t take 10 years to devise the basic system for nothing.